More Than a Drop in the Bucket

If you’ve ever seen the 2007 film The Bucket List, you probably remember that it’s about a couple of terminally ill but amazingly energetic old guys (played by Morgan Freeman and Jack Nicholson) who set out to complete a mutual bucket list—the things they want to do before they die. They drive race cars, fly over the North Pole, visit the Taj Mahal, and ride motorcycles across the Great Wall of China.

It is easy to forget, though, that the real message of the movie is summed up by one item on their list: Help a complete stranger for the good. That’s what each man does for the other in the few months they share.

The movie popularized the bucket list idea. But the concept that it should include more than exotic trips and adventures seems to have gotten lost along the way. One survey found that 95 percent of Americans have bucket lists and that the most common goals involve travel. The website bucketlist.org says that the most popular goals today include swimming with dolphins, bungee jumping, and visiting a volcano.

There’s nothing wrong with taking a nice trip or seeking a few thrills—especially if you have the money to do it and you pick experiences that matter to you—rather than those that made the latest list of 1,000 things to do and places to see before you die.

But here is a question to ask yourself: If you never swim with dolphins, will you regret it on your deathbed?

“None of us know when our time is going to be up,” says Dorian Mintzer, a Brookline, Massachusetts, psychologist who works as a transition and retirement coach and is the author of The Couple’s Retirement Puzzle: 10 Must-Have Conversations for Creating an Amazing New Life Together.

Mintzer urges her clients to really consider the lives they want to live and the legacies they want to leave behind. That is the path, she says, to building a better bucket list.

Make It Meaningful

In theory, “a bucket list is a great idea,” says Jim Emerman, vice president of encore.org, a nonprofit organization that focuses on intergenerational connection and helps older adults find meaningful second-act roles in the nonprofit world.

“It’s really important for people to think about what they want to do with the years they have left and what they want to leave as their legacy, for their family, and more broadly than that,” says Emerman.

But “a lot of people don’t think it through,” he says. “They tend to go to the usual: ‘Where haven’t I been, and what haven’t I seen?’”

So, what might be on a more meaningful bucket list?

For some people, the answers include nurturing relationships with big gestures like reuniting with an estranged sibling or small daily acts such as handholding walks with a spouse or storytime dates with a grandchild. Some lists might include spiritual or intellectual quests, from reconnecting with a childhood faith to learning a new language to spending more time in museums, libraries, and symphony halls. And many people who want to leave a better world will commit to more acts of kindness, giving, and service. They’ll find ways, Emerson says, to combine the things they enjoy doing with activities that lift up their families, communities, and humanity at large.

“Ultimately, these are things that will change your life more than any trip,” says Erica Brown, director of the Mayberg Center for Jewish Education and Leadership and an associate professor at The George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

Brown, who is the author of Happier Endings: A Meditation on Life and Death, recommends that people considering a bucket list try what might seem like a morbid exercise: writing their own obituaries. Better yet, she says, write one that would run if you died tomorrow and one that could run if you died many years from now.

“It’s a humbling experience that helps you think about how you want to be remembered,” Brown says. Many high achievers may find themselves pondering what The New York Times columnist David Brooks calls résumé virtues and eulogy virtues, she adds.

In a 2015 column, Brooks wrote: “The résumé virtues are the skills you bring to the marketplace. The eulogy virtues are the ones that are talked about at your funeral—whether you were kind, brave, honest, or faithful. Were you capable of deep love?”

Brown also says that it’s important to actually go to funerals, both for the solace you offer others and for your own good.

“No one goes to a funeral and doesn’t think about their own death,” she says. “It does sober us up and makes us think, ‘One day someone is going to stand there and talk about me.’”

If you do not like what your mourners might hear, she says, your bucket list is a chance to do something about it.

Creating the List

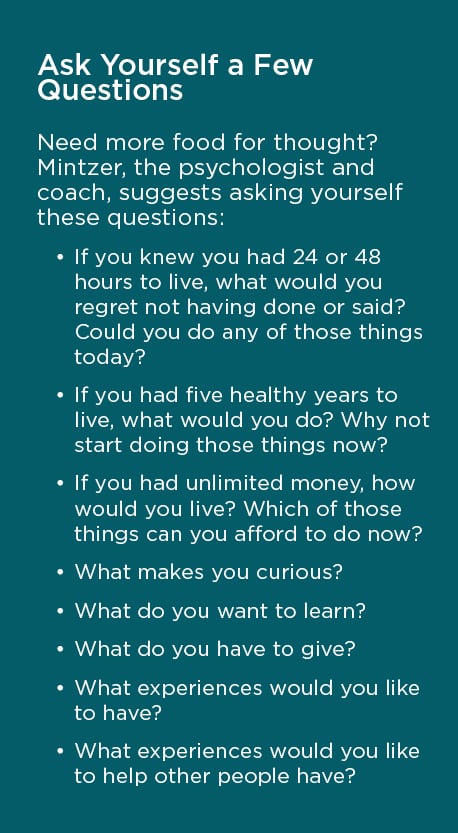

Asking yourself a few key questions just might help you come up with a bucket list that will “give more meaning and depth to your life,” Mintzer says. It may well include travel and adventure, but might also include new commitments to mentorship, charity, and other forms of service.

It’s really important for people to think about what they want to do with the years they have left and what they want to leave as their legacy, for their family, and more broadly than that.

Jim Emerman

Brown says she has listened to recordings of many deathbed conversations and is struck by one thing. When people express regrets, they are almost always about relationships—the people they lost touch with, the thanks they never gave, the forgiveness they never sought. Avoiding those regrets should be the starting point for any bucket list, she says.

British psychologist Philippa Perry put it this way in an interview with The Guardian newspaper: “What we should be doing in our bucket lists is learning how to be open with our own vulnerabilities so that we can form connections with other human beings … We don’t all like swimming with dolphins, but we are all made to connect to each other. That’s the really fun thing to do before you die.”

Go-To Gurus

With more than 40 years’ experience at her craft, psychologist and author Dorian Mintzer presents at a number of local, national, and international events and conferences each year, speaking on retirement transition issues. In her book The Couple’s Retirement Puzzle: 10 Must-Have Conversations for Creating an Amazing New Life Together, she shares smart, practical advice, engaging anecdotes, and helpful exercises.

Dr. Erica Brown is an accomplished author specializing in books about leadership, the Hebrew Bible, and spirituality. Brown has degrees from Yeshiva University, the University of London, Harvard University, and Baltimore Hebrew University. Her book Happier Endings: A Meditation on Life and Death was one of two of her 12 books to win the Wilbur and Nautilus awards for spiritual writing.