By gaining a holistic picture of your financial life, including your goals and risk tolerance, a financial advisor can customize your investments to meet your unique needs and desires. They do it through a combination of inputs that include financial planning insights, capital market acumen, and tax perspective. Behind the scenes, the financial advisor is constantly trying to position each client’s portfolio so that it stands to benefit from a multitude of potential future events.

What difference does it make if your portfolio is 60 percent stock and 40 percent bonds versus 80 percent stock and 20 percent bonds?

Both portfolios might be equally likely to fund your retirement spending needs, but the difference may lie in what you leave behind. Or it could impact how much flexibility you will have to indulge in things like an 80th birthday cruise around the world, a large donation to charity, or the decision to fund a grandchild’s education.

“Imagine three buckets,” says Mark Feldman, CAPTRUST principal and head of tax services. “The first bucket is the one that’s going to take care of you for the rest of your life, so those assets are going to be invested more conservatively. We call this the capital preservation bucket.”

“The second bucket—the liquid risk bucket—contains more volatile investments to help grow the portfolio. And the third bucket—the illiquid risk bucket—contains assets that will grow the portfolio but are not able to be accessed immediately,” says Feldman. “If you know your needs are taken care of with the capital preservation bucket, you become more risk tolerant with the excess.”

By separating your assets into buckets like these, a financial advisor can craft an investment portfolio that’s personalized to meet your goals.

Planning for Investment Goals

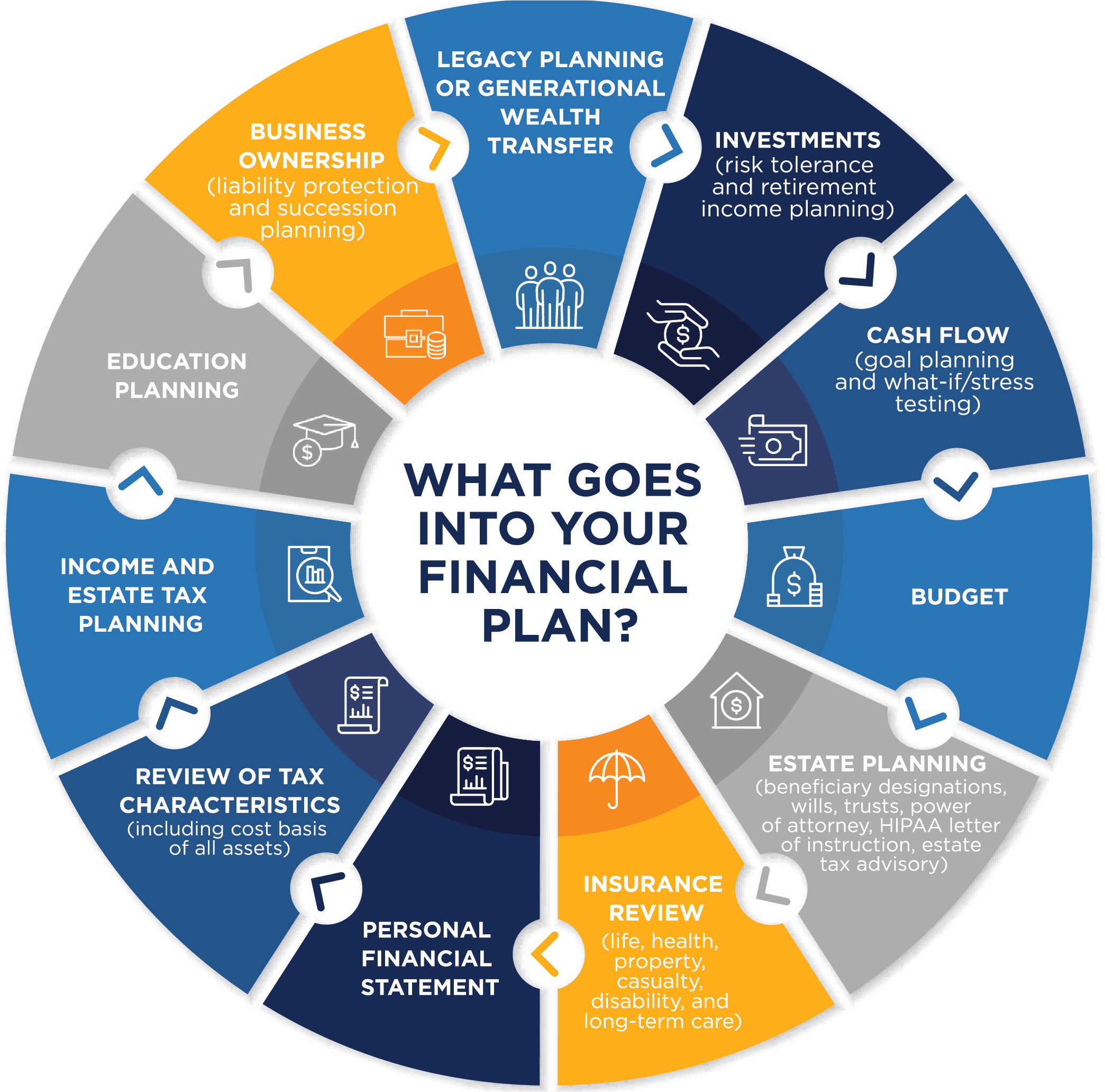

“We do the planning first,” says Briana Smith, CAPTRUST financial advisor. “Then the plan informs how we will manage the portfolio. First, we need to know your cash flow, your long- term legacy goals, your charitable intention—all those things. Then, we can align your portfolio appropriately to reach your goals.” A robust financial plan will take account of your income, expenses, investments, estate planning, insurance, taxes, and more.

Investment planning is one part of financial planning. It involves portfolio construction, selection of investments, monitoring, rebalancing, and trading for clients. It is the merging of investments with financial planning.

What is key, says Smith, is for the financial advisor to have a complete picture of your financial activities, needs, and goals.

The Investment Engine

To create that holistic picture, your financial advisor will strategize your unique investment plan, evaluating available investment portfolios to find the ones that best align with your goals and risk tolerance.

The hidden driver behind this investment plan is the investment team that designs each individual portfolio. This is the group of people responsible for doing deep research and weighing all the crosswinds—in the markets and the global economy—to guard portfolios against outsize losses that would compromise clients’ financial plans.

The investment group is always dealing with uncertainty, but it is also always planning and preparing for a wide range of outcomes. What happens in the markets if a war breaks out tomorrow? What happens if a war abruptly ends? The investment team faces the capital markets every day, making decisions about where they see opportunities and where they take risks, always with your interests in mind.

In other words, the investment team is responsible for developing a range of portfolio options with enough variety that your financial advisor can easily match your individual assets to the goals set by your financial plan. That means offering multiple investment engines that meet the needs and life goals of a large and diverse client base with unique tax profiles and circumstances. And it means balancing the risk and reward of any given security in a portfolio.

Proactive Tax Strategies

Perspectives from tax planning and advisory services are another big piece of the investment planning puzzle. To create a fully optimized investment plan, your financial advisor will pair your portfolio and investment opportunities with income tax strategies.

Eric Ensign, CAPTRUST financial advisor and tax consultant, says most people still think of doing a tax return as if it is only meant to take account of the past. “Most people are looking backward at the tax year that just occurred,” he says. “They’re usually not looking forward to the future with one eye on strategic tax planning.” That’s a potential missed opportunity.

The aha moment is when advisors can find synergies between tax planning, estate planning, and investment strategy that enrich your financial picture.

Tax advisory involves not only planning and strategizing but also considering tax implications and analyzing the tax impact of various investment strategies. As Jennifer Wertheim, CPA, a director of tax at CAPTRUST, explains, “Although tax might not be the biggest driver of a financial plan or financial decision, understanding and being aware of the potential consequences is important so that there aren’t surprises on the back end. If advisors can understand what your goals are, then they can plan and try to make your tax consequences complement the choices you’re making and the choices you plan to make in the future.”

Assembling Your Roundtable

Robust planning is simply not possible unless your financial advisor has all the necessary information at their fingertips, right when they need it. “Unless we’re looking at the tax return right next to the balance sheet,” says Feldman, “we’re going to miss the ways to connect them. We can save people more money when we view those two things together.”

Of course, that can mean more work upfront for you, namely in tracking down and uploading tax reports and account statements. But with recent technology, including secure files and uploads, it’s not as hard as it used to be.

The best-case scenario, says Jeremy Altfeder, CAPTRUST financial advisor, is when clients connect him directly to their other advisors, including tax professionals, insurance agents, estate attorneys, and more. “Then, if you are making big tax payments or moving money around, your CPA can just tell me what needs to happen and copy you on the conversation. Or the estate attorney can send documents directly to me so we can spare you the time and hassle. You probably don’t want to play the middleman, and frankly, you don’t have to,” he says.

This way, your financial advisor can act as a general contractor or project manager on your behalf.

Also, Altfeder says, “If it is only a financial advisor and a client working together, the voice of the financial advisor can sound a lot like the mom from the old Peanuts cartoons: ‘Wah wah wah.’ But when there are multiple perspectives from professionals with different expertise, that group of people is likely to generate better outcomes than one advisor alone.”

Creating this group of experts and putting them directly in touch with each other increases operational efficiency, reduces room for error, and can enhance the overall value of the advice. “You may be wary of bringing more advisors to the table,” says Wertheim, “because you haven’t needed to in the past, or you like to keep things simple, or you want to avoid fees. But having more people in the room—all your professional advisors talking to each other—adds tremendous long-term value that will exceed the short-term cost.”

Reducing Risk

What are the risks of not integrating your investment management with your tax and financial plans? In Feldman’s words, “Suboptimization of the options.” Or as Altfeder phrases it, “If your advisor can see only half of the picture, they can only give you half of the great advice.”

Wertheim agrees: “From a tax perspective, it could undermine your goals. If you aren’t aware that you are going to have a huge tax bill at the end of the year because of whatever strategies you’ve engaged in, it can leave you feeling very frustrated.”

“If you have a gain, yes, you’ll also have a tax bill at the end of the year, but hopefully we can minimize or strategize how to use that gain,” says Wertheim. “If you have a loss, that can also be beneficial. In fact, you might strategically plan to have a loss so that you can use it against something else. The key is to avoid unbeneficial losses.”

By integrating investments, planning, and tax, your advisors create a benchmark and can give you a clear-eyed vision of the future. You can practice scenarios so that you feel prepared. In this way, investment planning creates better outcomes, and it grows your confidence.

“We’re going to constantly test our assumptions about what the excess is,” says Feldman, “and we need you to guide us on how you want to allocate and design your plan. We need you to tell us what happens with the excess. And to the extent that we know there is excess, and the excess is unguarded by taxes, we look for ways to design the excess more tax-efficiently.”

Making Changes

For some investors, this type of long-term planning can feel prescriptive or limiting. Others wonder: What if this financial advisor isn’t the right one for me? What if I change my mind in five years? Remember that nothing is set in stone. Your financial plan is a living document.

Unlike the old days, when plans were reviewed only every three to five years, today’s technology allows advisors to make frequent updates and model different scenarios, like changes in spending, market environments, and tax rules. Your financial advisor will also help you edit your plan whenever there is a big shift in your financial situation, whether that means an unexpected gain, the selling of a business, or the loss of a family member.

You can also replan and recalculate when you feel your risk tolerance changing. For instance, if the market takes off, you can probably have a less risky portfolio and still achieve your life goals. Or you can choose to keep the pedal to the metal and leave a bigger legacy behind.

Right on Target

Smith says, “Having a path to follow—that is, the recommendations determined from the plan—and your financial advisor as an accountability partner is the biggest value to having a holistic plan, rather than just setting a portfolio. The plan will provide peace of mind when the market dips and give you clarity on what impact short-term decisions will have on your long-term projections.” Also, “Having a sounding board to discuss your goals and fears before making a big decision helps to make sure you aren’t acting out of emotion,” she says.

For Ensign, the beauty of integrating investments with tax and with financial planning is that advisors can provide more accurate, personalized guidance. Ensign says, “We often find ourselves challenging the investment thesis, which says, ‘This is the right thing to do right now. Sell this and buy this.’ But we can look at a client’s unique situation and say, ‘OK, that might improve the performance report, but for this particular client, it would be absolutely disastrous.’” That’s why it is critical advisors have a variety of portfolio options to choose from.

“It feels almost magical when it all comes together and we can find these big wins for people,” says Ensign. “We do this one thing over here, shift this other thing over there, and suddenly 1+1=3. Those moments don’t come for every client, every month, or every year necessarily. But when they do, that’s a bull’s-eye.”

Every family carries its own keepsakes. Some may have tangible value, such as jewelry, paintings, or baseball cards. Others have sentimental value, like photo albums, baby blankets, or toys. In most cases, the dollar value of these items is far less important than their role in a family’s story.

A Sense of Belonging

For Robyn Fivush, a professor of psychology at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, and author of Family Narratives and the Development of an Autobiographical Self, her grandmother’s candlesticks evoke strong memories. The candlesticks remind her of celebrating Sabbath services together and “make me feel a sense of history and tradition that extends beyond me,” she says.

These family stories “are important for the individual living in the present,” Fivush says. “They give us a sense of meaning and resilience that our family is a source of stability, love, and connection. We’re not adrift; we belong somewhere.”

Passing It Down

Stories and mementos transferred from one generation to the next can have a major impact on the younger generation. Based on her research, Fivush says, younger adults who are told these stories and understand what these keepsakes mean “have higher self-esteem, lower levels of depression, and less anxiety. They are more secure in who they are and consider their family an anchor in a difficult world.”

Not all stories conveyed from grandparent down to the next generation are uplifting. Some families have dark histories that can require a “lot of family story repair work,” Fivush says. But in most cases, these family treasures and tales “provide a cocoon that we’re not alone, that there’s a network of people who love and support us, and that even through difficult times, we can be resilient,” she says.

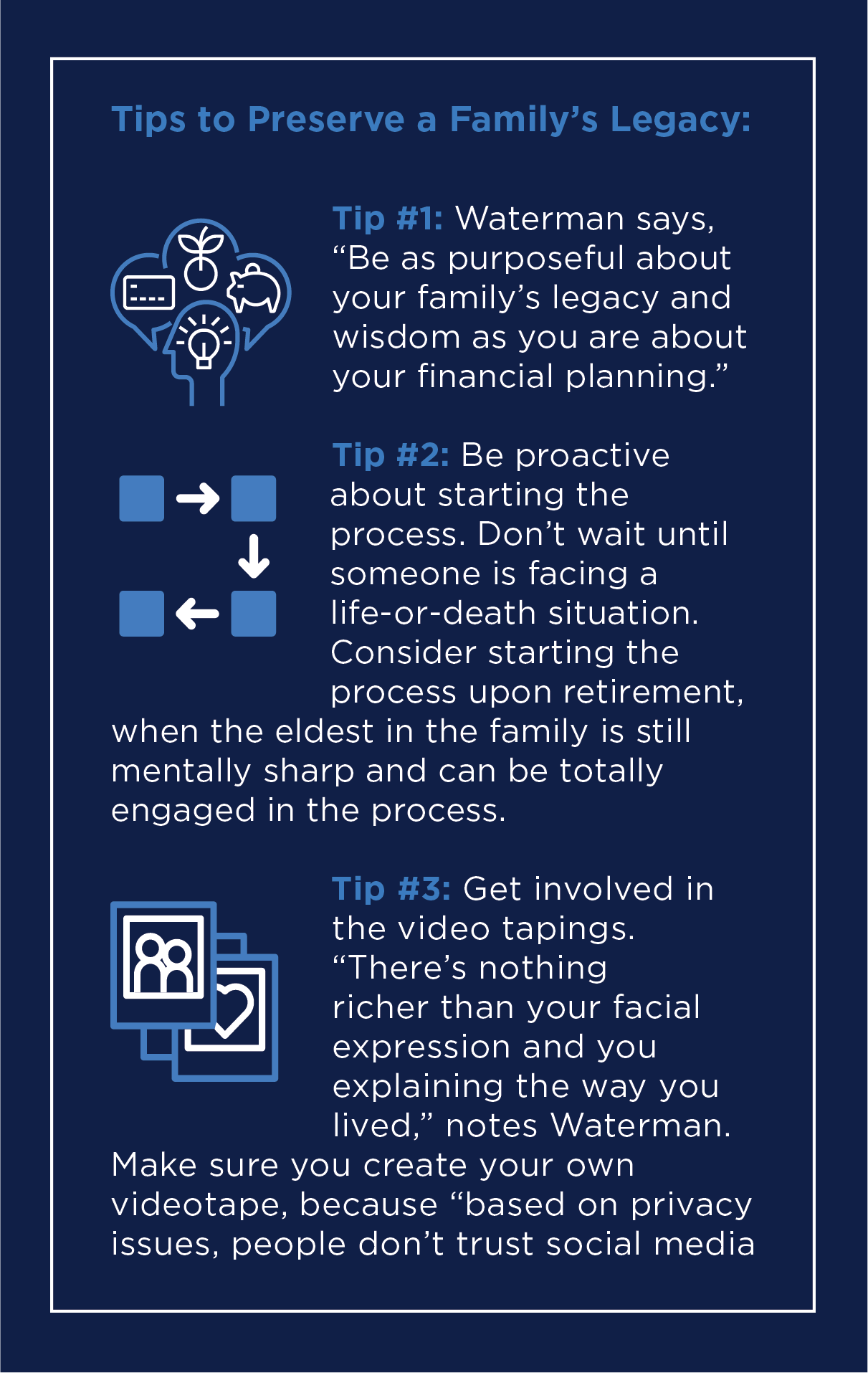

For Adrienne Waterman, the cofounder and CEO of Not Forgotten, a company that produces digital archives of families, the focus of heirlooms “is preserving intergenerational wealth and wisdom and will also help you secure your family’s financial future.” It helps pass the torch from the family’s past into the family’s future.

Waterman acknowledges that family valuables, such as jewels, diamonds, and watches, help build intergenerational wealth, but for many, “the intoxicating stories behind the creation or acquisition of that heirloom make them priceless for a family.”

Not Forgotten helps preserve a family’s traditions through video interviews, hybrid storage for physical tapes and digital media, and video archives. Waterman says that a family’s story invariably focuses on several themes—its lessons, values, mission, and family traditions. These can include family Christmas traditions or their story of survival. Its videographers attend memorial services and film eulogies to ensure a family’s legacy is preserved.

Waterman says the best time to start preserving a family’s history occurs at a pivotal moment in a family member’s life, like a grandparent’s retirement, a grandchild’s graduation from college, a couple getting married, or the birth of a first child. When a younger family member begins creating wealth and building their own family, that is also a propitious time to start the process.

When Denise May Levernick, a blogger at The Family Curator, received a trunk filled with her grandmother’s old photos, papers, and memorabilia, she became the family archivist to sort it all out. In the process, Levenick learned a few secrets from her family’s history, including stories of a kidnapping, a custody battle, and a disappearance that turned out to be an elopement.

The family knowledge gained through these heirlooms has had a positive effect on her son, who resides in the Boston area. He learned that his great-grandfather was a drummer and soldier in the Revolutionary War. When he took his children on the Freedom Trail and traveled to Concord, Massachusetts, seeing locations from the war meant a lot to them because of their family heritage.

When keeping these family mementos in a family of multiple siblings, Levenick advises picking numbers out of a hat so everyone has a chance to get their first choice and no one feels slighted.

How to be a Family Archivist

Here are a few additional tips that Levenick offers when a family member becomes the family archivist:

- Decide on exactly what your role is. In most cases, you’re preserving items for future generations.

- Be selective about what you keep. You don’t have unlimited space. Scan and digitize photos to save space.

- Pay attention to storage. Buy some office supply folders because they’re acid-free. Don’t keep things in the garage or attic because the temperature fluctuation can ruin them.

- Move papers into archival storage boxes or metal filing cabinets in your house, and keep them away from light, which ruins documents, photos, and textiles.

Financial advisors can also play a role in helping their clients assemble these family heirlooms because it’s part of a “holistic approach to retirement planning that goes beyond money,” says Steve Morton, a CAPTRUST financial advisor based in Greensboro, North Carolina. “Since advisors help with estate planning, finding ways to preserve family heirlooms can be part of that process.”

Morton says that when his dad died, there was a trunkful of photographs left, but Morton didn’t know who most of the people in the photos were. Cousins? Friends? Ideally, assembling these family mementos should take place before the death of a loved one.

Letting a loved one know what a favorite pendant meant to someone, where they bought it, and what it symbolizes turns an object into a family memory, says Morton. Preparing a video to explain what the heirloom means helps children or grandchildren understand its significance. “Understanding the story deepens the meaning,” he says.

Almost every family Waterman has dealt with has been surprised by the outcomes of seeing family members interviewed and recorded. “None of us sit around the dinner table and say, ‘Dad, what’s your secret to your happiness?’ In a video, what you learn about people you love is extraordinary.”

Several specialized companies help preserve these family heirlooms and provide time capsules and video memories, such as Not Forgotten, Try Saga, Farewelling, Lastly, Memorify, and Safe Beyond.

Q: With the high prices of gas, I’m considering buying an electric vehicle. But is it really cheaper in the long run than a gas-powered car?

Over time, yes. Although electric vehicles (EVs) are often more expensive to purchase than their gas-powered counterparts, EVs generally cost 4 cents less per mile to operate than a gas-powered car, saving you $8,000 over 200,000 miles. Eventually, your savings will outweigh your initial investment. Here’s how.

U.S. gas prices have been volatile in recent months due to shortages and supply-chain issues caused by the labor crunch and the war in Ukraine. Average prices for regular gas topped $5 per gallon in mid-June, according to AAA. Although prices have dropped since, sticker shock at the pump was enough to make many people consider switching to an EV car.

When comparing electric and gas cars, you should factor in the purchase price, ongoing fuel and maintenance expenses, and any tax incentives you might get. As an example, let’s compare the gas-powered Lexus ES 250, which has a base price of around $41,000, with an electric alternative: the Tesla Model 3.

The Tesla starts at $47,000, so it’s more expensive upfront. However, assuming you drive the car for eight years, the Tesla ends up cheaper in terms of total cost of ownership. In fact, after taking into account fuel, maintenance, insurance, taxes, and other costs, the Tesla works out to be 4.8 percent less expensive according to a February 2022 analysis by the data-technology firm Atlas Public Policy.

When it comes to trucks, with their significantly higher fuel consumption, there is an even greater cost difference.

The Ford F-150, which starts at around $31,500, would really hurt the wallet the next time gas hits $5 a gallon, costing a whopping $180 to fill the optional 36-gallon gas tank. Looking at the total cost of ownership over eight years, the electric Ford F-150 Lightning, which sells for around $40,000, is much more economical, at 17.1 percent less than the gas-powered version.

In general, EVs have lower maintenance costs as well. Note though that expenses will vary depending on whether you’re charging at a free, public station or one with a per-minute fee or you’re plugging your car in at home at night, when electric rates are lowest.

Also, consider that more federal tax credits could be available to eligible EV owners in the coming years. Starting next year, the Inflation Reduction Act will remove the current cap on the number of $7,500 tax credits that are available for each auto manufacturer, meaning that popular EVs will be eligible again. However, there will be a new income cap of $150,000 per individual ($300,000 per couple) to receive the credit.

Starting in 2024, buyers will gain the ability to transfer the tax credit directly to an auto dealer. This means consumers should be able to get $7,500 off of the purchase price at the time of purchase instead of having to pay first and claim the credit on their tax filings later.

Q: My children have already graduated from college, and I have leftover 529 funds. What should I do with them?

Children sometimes thwart our best-laid plans, but having extra money in a 529 college-savings plan is a pretty good outcome. Families can end up with leftover college funds for a variety of reasons, such as when a student gets their education paid for through military service or chooses to pursue a business idea instead of attending college.

As you probably know, 529 plan contributions are made with after-tax money and can offer a state tax benefit depending on where you live and which plan you used. When they’re used for qualifying expenses, distributions are tax-free and penalty-free. But when they’re used for nonqualified distributions, you’ll be on the hook for income tax plus a 10 percent penalty on the earnings.

One exception is if the student received a scholarship. In that case, you can withdraw the equivalent amount with no 10 percent penalty, although you will have to pay income tax on the earnings (not the principal).

If you were diligent in saving for college but now have unused funds, there are a number of ways you can use the money with little to no tax consequences.

To maximize 529 plan benefits for leftover funds, first look for another qualified way to use the money, keeping in mind that there is no time or age limit. Might your child pursue a graduate degree or a different field of study later on? If so, you could leave the funds in the account and let them grow tax-free.

Otherwise, consider whether someone else in the family might have educational expenses coming up. The 529 plan owner can change the beneficiary to another family member at any time with no tax consequences. And the definition of family includes a sibling, spouse, child, cousin, son- or daughter-in-law, brother- or sister-in-law, aunt, uncle, niece, nephew, and many other relatives. You’re even allowed to make yourself the beneficiary.

Qualified expenses include undergraduate or graduate tuition at accredited institutions, as well as room, board, books, and computer equipment. In addition, the SECURE Act of 2019 expanded allowed expenses to include K−12 tuition of up to $10,000 per year at a private, public, or religious school.

The SECURE Act also classified student loan payments as a qualifying expense. You can use up to $10,000 per beneficiary toward outstanding education loans. Ideally, someone in your family can take advantage of these funds.

Before you make any decision about your leftover 529 funds, check with your financial and tax advisors to make sure you know the impact on your specific situation. A financial advisor can also help you prevent or minimize overfunding.

Q: Some economists are predicting a recession, and I’m in my early 60s. How could this impact my retirement?

The decision to retire is complex and personal, more so when the stock market is volatile and the economic climate is so uncertain. But all the planning you’ve done over the years, such as analyzing various scenarios with your financial advisor, will come to good use in these final years of your career.

Even if gloomy forecasts are making you feel anxious, one of the cardinal rules of investing is to stay invested. Remember: Market timing is a fool’s errand. You’d need to have access to a magic crystal ball—not just once, but twice—to be able to know just when to get out of the stock market and when to get back in.

Instead of doing anything drastic, consider taking these financial steps to best position your retirement plan in case of a recession.

Take stock of your financial plan. Revisiting and updating your projected household expenses is paramount. That way, you’ll have a thorough understanding of the income needs from your portfolio.

You should also work with your financial planner to test the resilience of your nest egg against market fluctuations by rerunning projections and layering on several different what-if scenarios.

Calculate your cash cushion. The amount you need is based on personal preference. Building your portfolio buckets may help you become comfortable with the amount of cash you should hold. We recommend keeping about a year’s worth of expenses in cash as an emergency reserve. As you approach retirement, it can make sense to increase this amount, depending on your other sources of retirement income.

Recessions normally don’t last longer than a year. Having a cushion will insulate you from being forced to sell equities in a falling market.

Use tax-loss harvesting. With taxable accounts, it’s always prudent tax planning to be proactive about realizing any capital losses. They can be used to reduce your tax bill by offsetting previously realized gains. Anything you can do to give yourself an edge will help in the long run.

As always, you should speak with your financial and tax advisors about your personal financial situation before you make any decisions. If you don’t have a thorough financial plan that addresses your retirement under various market and economic conditions, now is a good time to consider one.

While that may sound thrilling to some, no doubt others are terrified about the prospect of pulling 5 Gs—an acceleration fast enough to cause riders to black out—from the height of a 40-story building. During peak summer, up to 1,400 thrill seekers per hour get to experience Kingda Ka.

Got Veloxrotaphobia?

How do you feel about roller coasters? Do you enjoy the thrill of trying out a new coaster with unknown twists, turns, and inversions? Or do you suffer from veloxrotaphobia—more commonly known as coasterphobia, the fear of being on a roller coaster?

The good news is that you have a choice. Peer pressure aside, if you find yourself at Six Flags Great Adventure, you can choose not to ride Kingda Ka. Instead, you can try out one or more of the other 13 coasters operating in the park. Presumably, you can find one to your liking. Or you can keep your feet firmly planted on the ground.

The stock market—with its breathtaking rises, falls, dips, and corkscrews—has been a metaphorical roller coaster over the past couple of months, even the past couple of years. But, like at Six Flags, you have the ability to dial in the level of thrills you can stomach with your investment strategy.

Dialing It In

Finding the right mix of stocks, bonds, cash, and other investments is critical. Building a portfolio with too many thrills can create anxiety and lasting fears about market losses, causing you to knee-jerk react when the inevitable market turmoil hits or, worse, deter you from investing at all. And too few thrills may keep you from fulfilling your financial needs due to insufficient returns over time.

The impact goes beyond strictly financial. “If a client goes to sleep every night worrying about their portfolio, it’s not a good sign,” says CAPTRUST Principal and Financial Advisor Justin Pawl. “That’s no way to go through life. Investments represent savings from the past and future financial security, so it’s understandable that clients have an emotional reaction to the fear of losing both.”

Therein lies the challenge of getting it right—balancing the need for returns with a ride that the client can stomach. While every investor wants outsized returns, remember: Those returns don’t come without risk. “The key is for clients to understand their risk tolerance and for their portfolios to reflect that tolerance,” says Pawl. Of course, finding the right risk level for yourself and your financial goals is easier said than done.

Part Science, Part Art

Financial professionals and academics have explored many ways to divine investors’ risk tolerance, including questionnaires, software, and simulators. Monte Carlo simulators, for example, illustrate risk by using historical or projected returns and are excellent tools for helping investors understand the impact their decisions have across many potential future market outcomes— many of which will be very good.

An investor who is in thinking mode is likely to see the benefits of a riskier strategy and weigh the probabilities in a rational way. That’s why “even the best tools, like Monte Carlo simulations, may actually lead to higher perceived risk tolerances,” says Jim Underwood, CAPTRUST senior director and portfolio manager.

While some tools are better than others, even the most sophisticated tools fail to capture the emotional element of investing. They depend on the parts of your brain responsible for rational thinking and do not fully capture the impact of your fight-or-flight response when market turmoil strikes.

“The emotional reaction to market volatility is the primary risk for investors, because unlike roller coasters, where the rider is buckled in to ensure they finish the ride, investing doesn’t have any seat belts,” says Underwood.

“I think investors most often get the emotional part of investing through downturns wrong, because when markets are selling off, it is always accompanied by a lot of negative information,” says Pawl. “Investors underappreciate the toll it will take on them because, on top of declining account values, all the news is bad. Breathless ‘breaking news’ media reports, conversations with friends and colleagues about how awful the market is, and sensational internet forums add fuel to the fire.”

It’s important to remember that volatility is not risk, says Pawl. “Crystallizing losses in a down market, creating a permanent capital loss, is risk.” This emotional reaction happens when the amygdala— the part of your brain responsible for the fight-or- flight response—activates, releasing stress hormones and preparing your body to either fight for survival or to flee to safety.

When emotions are running high, the decision-making process becomes compromised, and it’s easy to lose sight of the analysis and discussion that led to your portfolio strategy.

Finding Perspective

“Unfortunately, risk tolerance is often only knowable after the fact, when you have exceeded it,” says Underwood. As always, you can employ strategies to help manage your emotions and set the stage for future market volatility.

Talk it through. Experience—living through numerous market cycles—matters and highlights the value of a financial advisor or other trusted sparring partner who can provide perspective when your amygdala kicks in. Many people process their thinking by speaking, so talking through your feelings and anxieties can be a helpful way to expand your thinking. The more viewpoints, the better. Open discussion will add nuance to your ideas and help ensure you are thinking rationally. Your brain literally cannot process fear when you’re having a rational conversation with a friend.

Rerun your plan. Just after a market pullback is always a good time to revisit your financial plan. A sound financial plan will take into account a wide range of market scenarios. Knowing, for example, the portfolio hurdle rate needed to fund your important life goals can provide both the information required to dial in an appropriate level of portfolio risk and the confidence that you’re on the right track. You may find that it will be quite easy to achieve your goals, so you can worry less about market pullbacks and won’t need to take an extraordinary amount of investment risk to get there.

Reflect while it’s fresh. History is also a good teacher and can help blend the art and science of risk taking. “We’ve just been through a big market pullback, and while we’re not back to previous highs, markets are likely to recover,” says Underwood. “Is it time to ride the same roller coaster again, or should you find one that is designed to be less thrilling?” Make sure you don’t pass up the opportunity to reassess your feelings while the memories are still fresh. “A week after you ride, the thrill is gone,” he says.

If the drops, dips, and winding turns of our recent roller- coaster stock market make your head spin, you may be on the wrong ride. But don’t head for the hills. Remember that you can find a less thrilling ride, one that you will be comfortable revisiting. At a minimum, you should take this opportunity to reflect on your feelings to better learn the art of fine-tuning your risk tolerance.

On October 13, the Social Security Administration announced an 8.7 percent increase in Social Security benefits to account for rising inflation. This is the largest cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) since 1981 and amounts to an extra $146 a month for the average retiree, according to the Social Security Administration.

Since 1975, Social Security benefits have been adjusted automatically based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which is a measure of price fluctuations in goods and services. In the third quarter of each year, the Social Security Administration compares the average CPI for July, August, and September to the same timeframe in the previous year and increases Social Security benefits accordingly.

The intention is for each year’s COLA to keep pace with each year’s average inflation so that Social Security recipients will have equivalent buying power despite price increases. Social Security is the single largest source of retirement income for most Americans.

This 8.7 percent COLA goes into effect with December 2022 benefits, which means most recipients can expect to receive the higher amount starting in January 2023. All recipients can expect to receive letters in December detailing their specific benefit rate for next year. You can verify your increase by logging into your account on the My Social Security website.

To understand more about how the 2022 COLA may affect your personal finances, talk to your financial advisor.

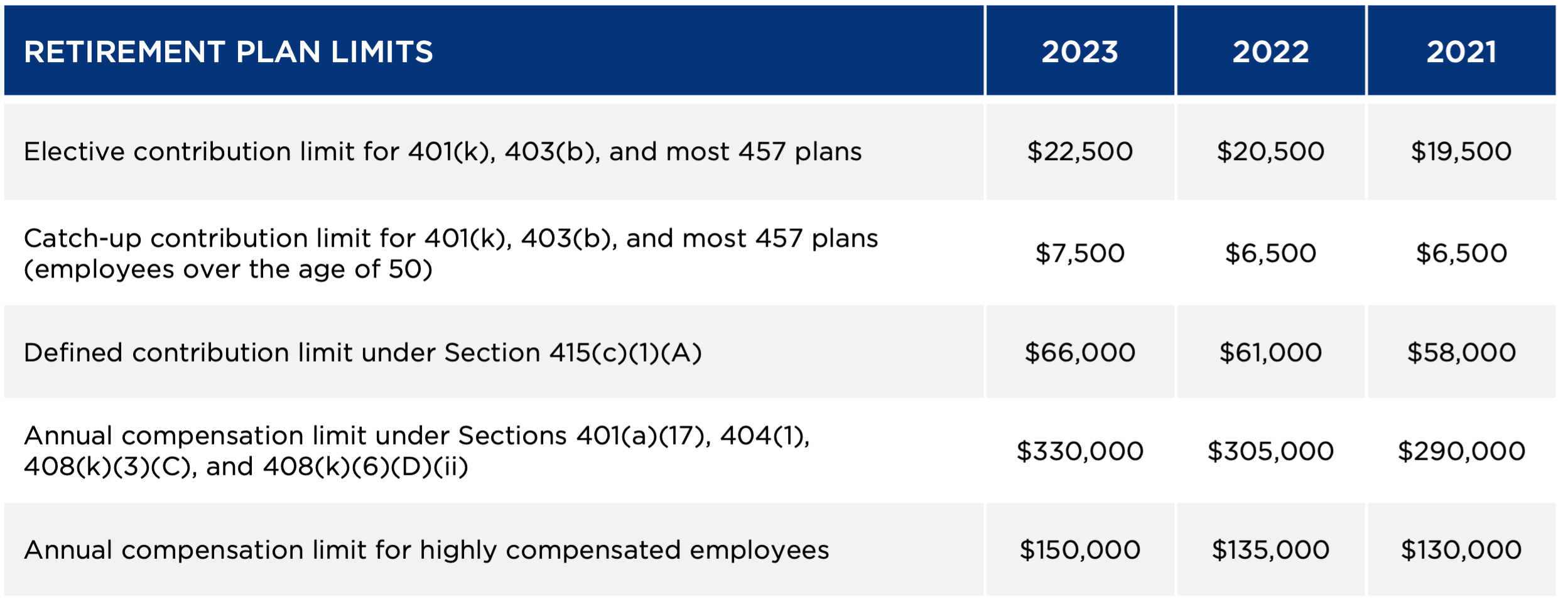

The Internal Revenue Service announced its annual update to dollar limitations for pension and other retirement plans for tax year 2023. Some of the retirement plan-related limitations are changing because the annual cost-of-living increase met the statutory threshold that triggers their adjustment. The table below provides a few highlights.

For more information, please contact your CAPTRUST Financial Advisor at 800.216.0645. Click here to download a copy of this table.

Nonqualified deferred compensation (NQDC) plans allow employers to offer tax-deferred savings opportunities to key employees, typically executives. Unlike qualified plans—like 401(k)s, defined benefit pensions, or profit-sharing plans—NQDCs operate mostly outside of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). This makes it possible for employers to offer them only to a subset of employees and to create a level of flexibility not permissible within qualified plans.

The benefits to employees are clear: Participants can make pre-tax contributions of their base salaries, bonuses, or other compensation in one tax year, then withdraw the assets—and therefore pay income tax on them—in a later year. In the meantime, the deferred funds can be self-directed in a portfolio that is typically similar to the employer’s qualified plan menu and allows the possibility of growth.

The biggest advantage to employers is the ability to leverage NQDC savings as an executive benefit when hiring, retaining, or rewarding employees. In today’s tight talent market, NQDC plans feel especially attractive, and the industry is seeing a steady uptick.

Industry Uptick

In recent years, the NQDC industry has seen a shift to larger plans, and total assets have increased 130 percent, from $80 billion in 2015 to $183 billion in 2021, according to the 2021 “PLANSPONSOR NQDC Market Survey.” As the Government Accountability Office shared in a January 2020 report on private pensions, the vast majority (83 percent) of S&P 500 companies now offer nonqualified plans.

There is also an increase in employee participation. In fact, according to the same PLANSPONSOR survey, 66 percent of employees who were eligible to enroll in their employer’s nonqualified plan chose to participate, up from 53 percent in 2018.

“These trends can be attributed to historically low unemployment and the greater need for employee retention,” says Katie Securcher, a manager on CAPTRUST’s nonqualified executive benefits team. “For employers looking to expand their holistic benefits offerings, nonqualified plans offer a way to further entice key executives to join and stay at their organizations.”

Discretionary Eligibility

Part of the uptick may also be the result of several key plan design elements that have increased in popularity in recent years. These features allow nonqualified plans to have a greater degree of flexibility that benefits both the employer and employee. The first is flexibility in who is eligible to participate.

“While nonqualified plans can, in theory, be open to employees at many different levels, they are typically focused on those employees who are limited in other retirement savings vehicles that plan sponsors offer,” says Jason Stephens, senior director of nonqualified benefits at CAPTRUST. For many organizations, this means taking a strategic approach that focuses on a few employees at the top of the organization.

As an example, in 2022, under ERISA law, 401(k) participants could save a maximum of only $20,500 and plan sponsors could provide a match on savings up to only $305,000 of compensation. An executive who earns $500,000 a year is therefore only able to save a combined total of $41,000, or 8.2 percent of their salary, with dollar-for-dollar employee matching. But retirement best practice is for employees to save 10 to 15 percent to maintain their current lifestyle.

These limitations mean highly compensated executives who are contributing the maximum amount and receiving generous employer matches still would not be able to maintain a retirement lifestyle that aligns with their expectations. NQDC plans can provide an additional savings opportunity that will help them bridge the gap.

Typically, these plans are designed for no more than 10 percent of a total employee population, although in practice, they have been more limited. Eligibility is most commonly based on job title or base salary. In recent years, Stephens says, organizations are expanding eligibility to attract new hires and retain valuable employees who may have been previously ineligible for the company’s NQDC plan.

In its “2021 NQDC Market Survey,” Plan Sponsor Council of America (PSCA) found that 6.1 percent of total employees were eligible to take part in nonqualified plans in 2020, up from 5.2 percent in 2018.

“Determining who is eligible for nonqualified plans means finding the right balance for your organization,” added Stephens. “It’s the balance of identifying employees who will truly benefit the most from this type of plan but also not overextending the benefit. Having a bit more discretion in who can participate can be impactful in the recruiting process, especially if those employees are leaving behind a nonqualified plan at their previous organizations.”

Cost and Operational Efficiency

Another aspect contributing to the increased popularity of NQDC plans is the low initial and recurring costs of offering these plans. “Obviously, there will be fixed costs relative to some of the operational aspects of the plan, but when you look at those fees in totality, the per-person expense to have this offering on the table is usually small,” says Stephens.

For efficiency, most plan sponsors (61.2 percent) bundle their NQDC plans with the same administrator that is managing their qualified retirement plan, according to PSCA. “Administration is simply more efficient when you’re sharing information with just one party,” Stephens says, “and bundling helps create a cohesive experience for participants too, so it’s mutually beneficial.”

It’s worth noting that, in recent years, a few of the large qualified recordkeepers have acquired some smaller nonqualified recordkeepers, allowing for better bundled solutions and improved operational efficiency.

Contribution Flexibility

Perhaps the most attractive feature of NQDC plans is their flexibility to include both sponsor and participant contributions. According to PSCA, while nearly all plans (93.5 percent) allow participants to defer their base salary and bonus pay (90 percent), until recently, many plan sponsors didn’t allow for employer contributions. Now, both matching and discretionary employer contributions are becoming more common.

“There’s huge flexibility in the amount that employers can contribute,” says Securcher. “If they build the right provisions into the plan, employers can basically give a contribution to all participants within the NQDC plan or a subset of NQDC participants, can assign different vesting schedules to different individuals, or can simply let the employer discretionary contribution option lie dormant until they need or want to leverage this provision.”

Securcher explains, “Some organizations smartly incorporated employer discretionary contribution allowances when they created their plans, but they’ve never used them. Now, faced with a competitive labor market, they might say ‘OK, let’s give people bonuses via NQDC plans because we need to keep our folks here.’ They’re a good option to have available, even if you’re not going to utilize them all the time.”

Another popular employer contribution formula allows discretionary non-matching contributions plus a restoration match designed to fill the gap between 401(k) contribution limits and Internal Revenue Service (IRS) limits.

Distributions and Withdrawals

There are two key points to understand about NQDC plans and distributions. First, these plans are not useful solely for retirement. Second, unlike a qualified retirement plan, when taking withdrawals from an NQDC, participants must schedule distributions in advance.

For participants who want to take a withdrawal, there are six lawful types of triggering events: a fixed date, a separation from service, disability, death, a change in ownership of the company, or an unexpected emergency that could not have been planned for, like a sudden medical expense. A large tax bill, volatility in the stock market, or a change in the company’s financial health are not considered triggering events.

Usually, NQDC plans incorporate what’s called a fixed date election, in-service election, or specified payment date election. “They all mean the same thing,” says Securcher. “Basically, the employer is giving each employee the option to pick a date in the future when the employee is still working with this company, and that’s when the account will start paying out.”

Fixed date elections are helpful to participants because they allow people to plan for big expenses that aren’t tied to retirement goals, like sending a child to college or buying a second house. “Of course, the money is taxable when it’s distributed,” says Securcher, “but unlike a 401(k) plan, if you take money out of an NQDC before you are 59 1/2, you won’t be penalized.” Some plans only offer lump-sum payment options, while others offer the option for installments.

Participants can elect the time and form of fixed-payment accounts during enrollment. Typically, the date or form of payment associated with a fixed-payment account can be changed, but those changes are subject to 409A restrictions. According to PSCA, more than 60 percent of plan sponsors allow for emergency withdrawals, but 83.3 percent of those organizations report that none of their participants took one in 2020.

Enhanced Investment Menus

By default, and for administrative simplicity, most plan sponsors simply mirror the investment options available in their qualified plans. Securcher and Stephens say roughly half of CAPTRUST clients choose that option.

But because NQDC plans are not subject to laws regarding fiduciary responsibilities, they sometimes have broader investment menus than qualified plans. This is another attractive benefit to employees, especially if your key executives represent a different investor profile than your employee base. They may be saving for specific life goals, may have a more advanced understanding of investments, or may have better access to outside advice.

For instance, one participant may want to defer their entire compensation for five years in preparing to pay for a parent’s long-term care. Another participant may want to use their NQDC plan as a retirement savings vehicle over the course of the next 20 years. These choices will drive different investment behaviors that may require an expanded investment menu.

Retention Features

NQDC plans work as an employee retention tool not only because they are attractive savings vehicles but also because employers are allowed to apply discretionary retention features. For example, an employer may choose to give the employee a large bonus that vests over the course of five to ten years, thereby incentivizing retention.

Unless a plan has specialized provisions, typically a separation from service will trigger a distribution. This can cause a large tax bill for employees who leave the company unexpectedly. In some cases, leaving before retirement can also result in the forfeiture of unvested employer contributions.

“The level of choice that a plan sponsor has in how it designs its NQDC plan will vary by recordkeeper,” says Stephens, “but overall, these plans are highly flexible and highly attractive to executives, especially in today’s talent market.”

An NQDC offering can help you attract new executive talent but also retain and reward your current team. After all, turnover is costly, and executive turnover costs even more.

For employers who are just getting started, Securcher says, “Build the provisions in now as a safeguard. Then, you can bring them out later with the big guns if you need them; for instance, when you’re building out your executive team. And for existing plan sponsors, if you don’t have an NQDC plan in place, talk to your financial advisor about possibly adding one in the future.” Your financial advisor can help you determine the best plan design for your organization and your future needs.

The economy, like the growing season, is cyclical. Farmers know when to plant seeds so that crops peak at just the right time. Along the way, they rely on weather forecasts and real-time measurements of soil conditions to fine-tune their use of water and fertilizers. They do this because the stakes are high; the upfront cost to put a crop in the ground is enormous, and a failed harvest would be disastrous.

The Federal Reserve and other global central banks are, likewise, tenders of the global economy. They can adjust monetary policy to provide stimulus when conditions slow down and tighten when growth and inflation overheat, just as farmers can adjust nutrient applications to speed up or slow down crop maturation.

But unlike farmers, the Fed lacks real-time feedback. When it pulls a lever to tighten conditions, the extent of that change will likely not be fully known for six to 18 months. It’s always operating in the dark.

Today, it is widely believed that the Fed acted too late to effectively curb inflation. They didn’t get the seeds in the ground fast enough. Now, they’re making up for lost time through the fastest tightening cycle in the modern era, effectively driving a massive tractor at full speed at midnight. If they move too fast or understeer, they could plow right through a fence and push the economy into a recession.

Third-Quarter Recap

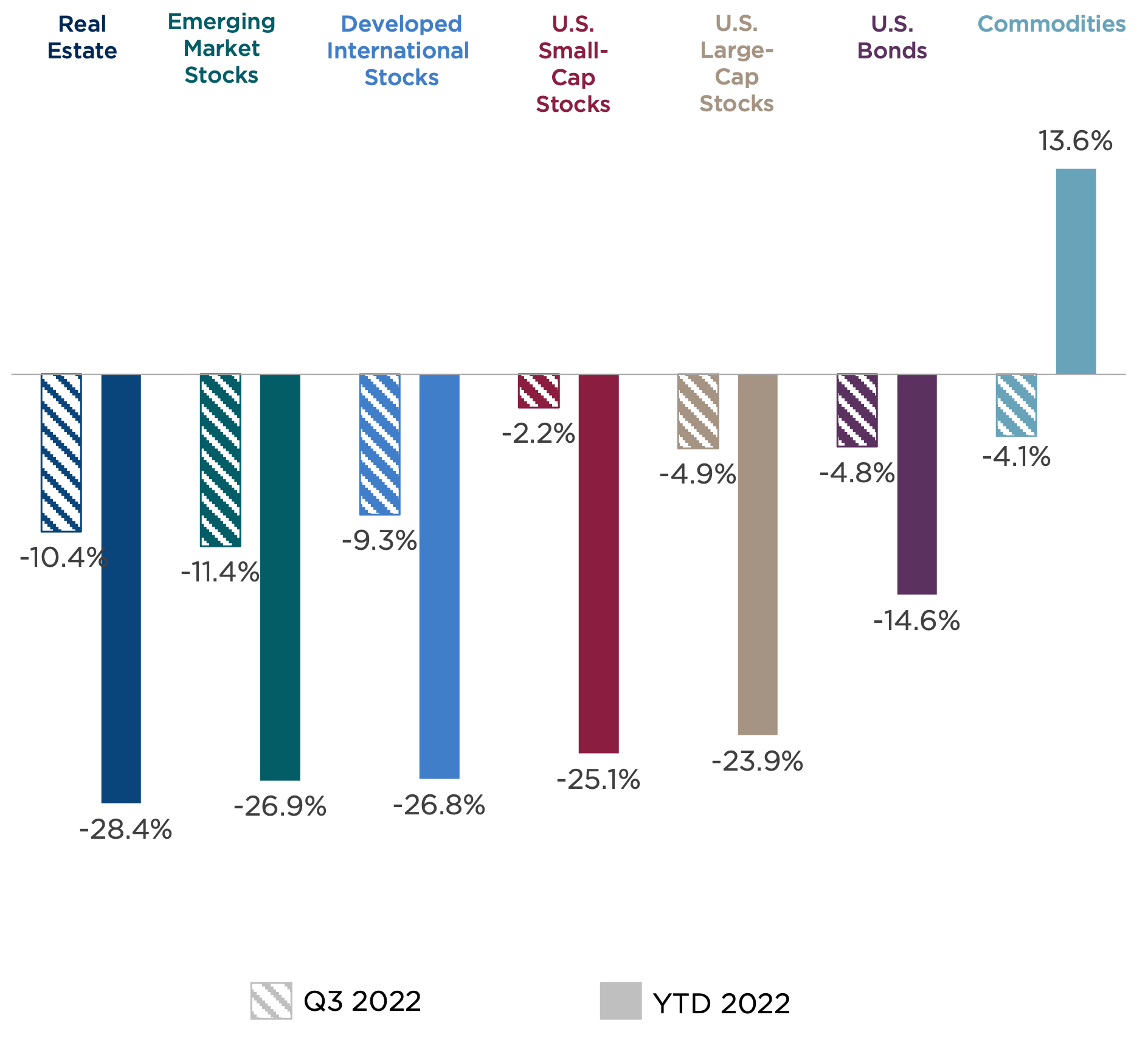

All major asset classes ended the third quarter with losses, ranging from 4.1 percent for commodities to 11.4 percent for emerging markets. It was a mirror image of second-quarter results that showed the same pattern of diversifrustration, leaving even well-diversified investors frustrated.

Figure One: Asset Class Returns (Third Quarter and Year to Date 2022)

Sources: Asset class returns are represented by the following indexes: Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (U.S. bonds), S&P 500 Index (U.S. large-cap stocks), Russell 2000® (U.S. small-cap stocks), MSCI EAFE Index (international developed market stocks), MSCI Emerging Market Index (emerging market stocks), Dow Jones U.S. Real Estate Index (real estate), and Bloomberg Commodity Index (commodities).

U.S. equities delivered a wild ride during the quarter, with large-cap stocks rising by more than 10 percent by mid-quarter before plunging into negative territory, resulting in a 4.9 percent loss for the quarter. Small-cap stocks fared modestly better than their large-cap counterparts, and growth stocks outperformed value stocks for the quarter.

Outside the U.S., European stocks faced further declines amid the ongoing war in Ukraine and resulting energy shortages, which grew worse after simultaneous leaks were discovered on two major gas pipelines. Led by rising energy costs, Eurozone price inflation reached double-digit levels in September. Within emerging markets, the growing prospects for slowing global trade, continuing struggles in China, and an exceptionally strong U.S. dollar created significant headwinds.

For bond investors, this no-good, very-bad year grew worse in the third quarter as core U.S. bonds declined by another 4.8 percent, bring their year-to-date return to negative 14.6 percent. This represents the worst-ever return at this time of the year, eclipsing the prior largest drawdown by a wide margin, as seen in Figure Two. One reason for this outsized reaction is that starting rates were so low; if you start a rate-hike cycle with a 5 to 7 percent yield, the income stream helps offset the price declines caused by rising rates. This year, we began with a 10-year Treasury yield of just 1.5 percent, leaving little yield cushion to offset price declines. Rising interest rates and concerns about potential recession also added to 2022 difficulties for public real estate.

Although commodities also declined 4.1 percent for the quarter, it remains the only major asset class with positive returns (13.6 percent) on a year-to-date basis.

Figure Two: Core Bond Prices on Pace for Historic Losses (1976-2022)

Sources: Bloomberg, CAPTRUST Research; Data as of 9.23.2022

While these returns will leave any investor feeling glum, there is a silver lining. Existing bond prices fell as their yields rose. This means that long-term investors can now pick up bonds with the potential to provide meaningful income. Even 10-year Treasurys are now paying yields approaching 4 percent: their highest level in more than a dozen years.

The Pest in the Field: Inflation

When markets are volatile, it’s important to attempt to cut through the noise and focus on the main event. Currently, all eyes are fixed on inflation and the Fed’s attempt to control it.

Consumer Price Index (CPI) data for the month of September all but cemented the Fed’s course toward another outsized 0.75 percent rate hike next month. CPI increased by 8.2 percent from a year earlier, which was a slight decline from the August reading. However, core CPI, which excludes some of the more volatile categories such as food and energy, which are less affected by monetary policy, rose to 6.6 percent from a year ago, the highest level in four decades.

Another issue with the inflation we’re experiencing today is its source. Some inflation can be classified as demand-pull inflation, which happens when strong consumer demand outpaces supply, causing prices to rise. This type of inflation was felt during and after the pandemic, as consumers raced to buy goods during lockdown, then rushed to consume services as the economy reopened. Demand-pull inflation tends to be reactive to Fed policy moves.

In contrast, cost-push inflation occurs when supplier costs increase, whether through rising input and energy prices, production bottlenecks, supply-chain disruptions, or higher wages. These issues are less affected by the Fed’s toolkit and may require other forms of policy change to move the needle.

Laser-Focused Fed

The goal of any central bank is to establish economic confidence by keeping inflation low and stable while supporting an environment for a healthy labor market and growth conditions.

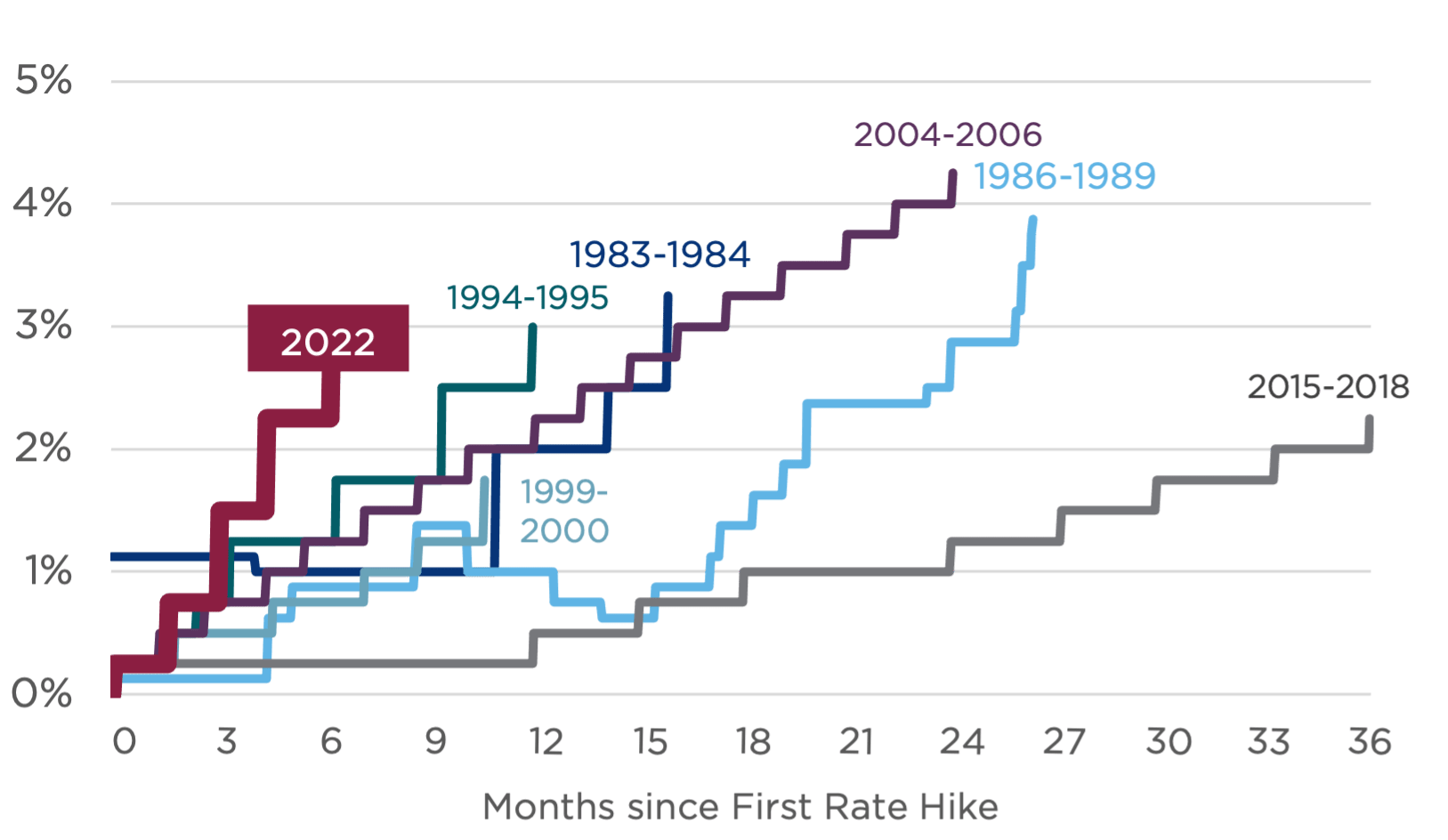

However, the high and rising level of inflation has sharply narrowed the Fed’s focus. High inflation that risks becoming entrenched has prompted the Fed to act far more swiftly than ever before, as the steep incline in Figure Three shows. Continued strength in the labor market provides room for this hawkish stance. The Fed seems resolved to tighten until inflation comes under control, even if it causes pain elsewhere in the economy.

Figure Three: The Fed’s Historical Tightening Pace

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, CAPTRUST Research

How did the Fed get itself into this position? As stated, Fed policy acts with a lag. It’s like trying to park a truck with the steering wheel and brakes on a 60-second delay. It seems the Fed temporarily forgot this fact in early 2021 as inflation began to accelerate but was explained away as temporary or transitory. Yet, even as it became clear late last year that inflation was a growing problem, the Fed did not raise rates until March.

The Fed’s objective is to engineer a soft landing—containing inflation without triggering a recession. But historically, this has been difficult to achieve, notwithstanding the added complexity facing the economy today. Over the past 60 years, throughout the course of eight recessions, we have seen only one true soft landing, suggesting that the odds of a Goldilocks outcome are poor.1

The last nine months are a stark reminder of what life is like when we have elevated inflation and an aggressive Federal Reserve. Markets especially dislike such policy uncertainty because it is not driven by fundamental or technical factors that can be analyzed but, rather, by the decisions of a small group of people and their various spreadsheet models, both of which are opaque.

Recession Complexion

Assuming that a soft landing isn’t achieved—a hope that’s growing dimmer by the day if you trust the continued and worsening inversion of the yield curve—then the next question on investors’ and business leaders’ minds is what the subsequent recession would look like.

Despite the significant market reaction so far this year, there are several positive signs that provide hope that even if the economy slips into recession, it could be a shallow and less painful one. Such factors include:

1. The Labor Market

One fact that has bolstered the Fed’s aggressive policy this year is the continued tightness within the labor market. There are still approximately two job openings for each unemployed worker today. And like any scarce resource, we could see hoarding behavior for talent within companies, which could prevent the mass layoffs that often accompany a recession.

2. Housing

With declining home sales and mortgage rates that have more than doubled from 3.2 to 6.9 percent this year, we expect to see weakness in the housing market. However, mortgage balances have increased only modestly over the past 20 years, while home equity has soared. This equity cushion should help keep a housing correction from becoming a crisis.

3. Strong Balance Sheets

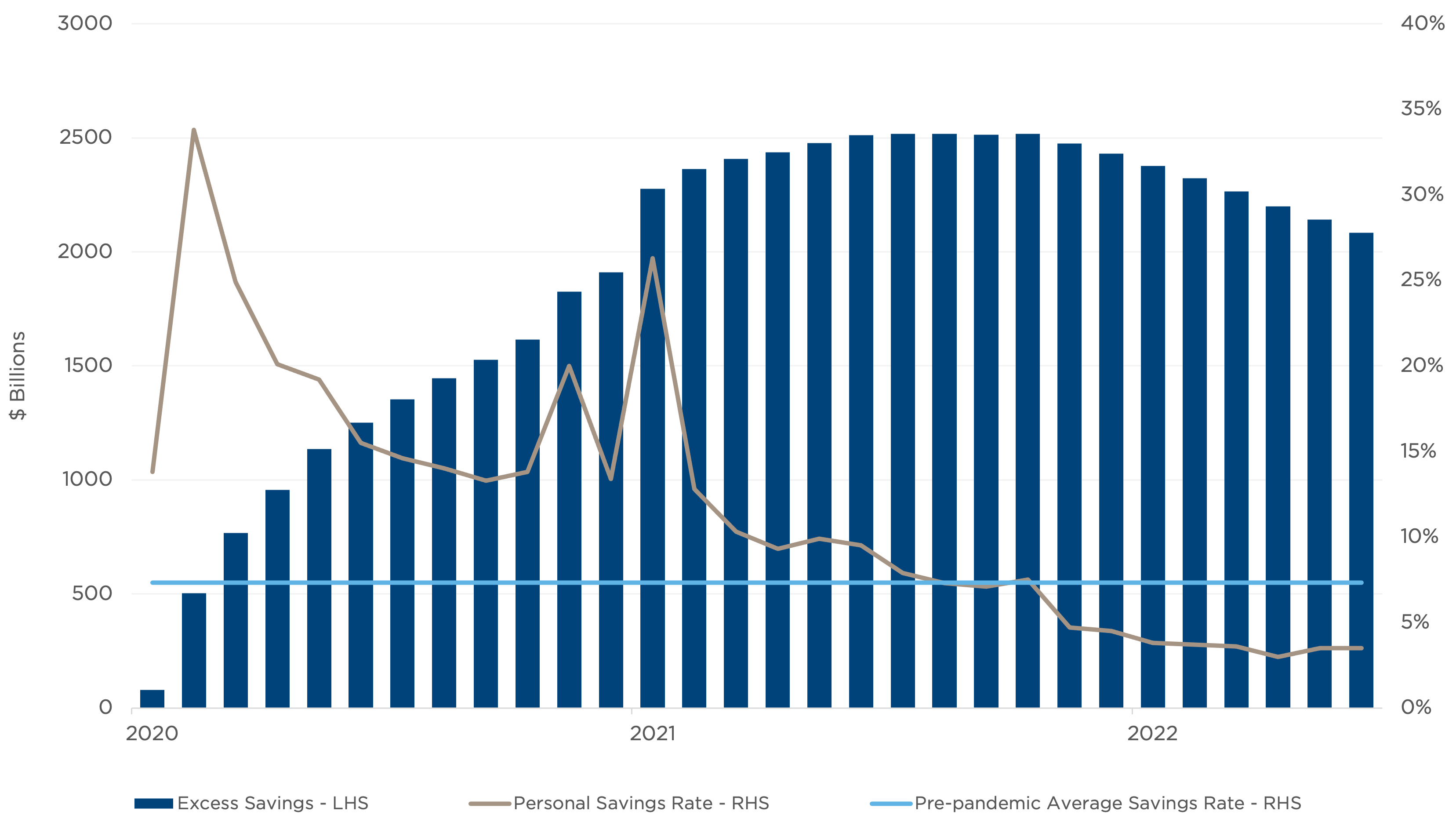

Despite low levels of consumer confidence, consumer spending has remained robust. This is due in part to strong household balance sheets that maintain a $2 trillion surplus of excess savings. However, spending began to slow in August, and the personal savings rate and levels of revolving credit have both deteriorated, suggesting that households are dipping into savings and tapping into home equity and credit cards to maintain spending or compensate for rising prices. Figure Four shows the volume of excess savings and the personal savings rate since the pandemic began in March 2020.

Figure Four: U.S. Excess Savings

On the flip side, while these sources of strength suggest a mild recession, it very well could be a longer recession as well. Typically, the Fed can turn on a dime at the first sign of recession to help soften the blow with lower borrowing costs. But this time, in an inflation-driven recession, it likely won’t have this luxury.

While the Fed could take other actions to ease financial conditions—such as suspending its quantitative tightening program—the prospect for rapid rate cuts is slim. In short, the length and severity of the recession will be driven by how high and sticky inflation proves to be relative to the Fed’s pain tolerance as the economy slows and unemployment rises.

What Might Happen

We believe the chances of a recession next year have increased to greater than 50 percent. However, stocks typically reach their bottom before the onset of a recession (or in hindsight, when it is declared). Much of the pain has already been priced in.

As we’ve said many times, the economy isn’t the market, and the market isn’t the economy.

The outlook for stocks remains clouded by uncertainty, which usually translates into volatility. Stock prices have declined significantly this year, while profit margins have remained elevated. As a result, measures of valuation, such as the price-to-earnings ratio, have fallen from well above their long-term average to below average.

On one hand, lower valuations improve the outlook for long-term stock investors, particularly when combined with depressed investor sentiment. But so far, we have witnessed a bear market in valuations but not earnings. As the risk of recession grows, stocks could come under further pressure through declining fundamentals while an exceptionally strong U.S. dollar dilutes the overseas earnings of U.S. companies.

Amid this global uncertainty, the competitiveness of the U.S. economy has never been more visible. While we may not be able to escape a recession, our economy is more resilient than those of much of the rest of the world, benefitting from abundant natural resources, a well-developed infrastructure, a stable financial system, and high levels of productivity.

Cautious Optimism

There is a Chinese proverb that explains, “The corn is not choked by the weeds but by the negligence of the farmer.” As large, dynamic, and resilient as the U.S. economy may be, it cannot escape trouble caused by the policy decisions—or mistakes—of a small group of people. We are witnessing this reality today within the UK, where policymakers appear to be fighting themselves with fiscal stimulus and tax cuts amid high inflation that the Bank of England is trying to control.

Given the high degree of uncertainty facing the markets today, we are maintaining our cautious outlook. At the same time, we are watching for signs that the worst is behind us. Until then, in a world with an expanding range of potential outcomes, the best defense is, as always, a well-diversified portfolio aligned with your personal risk tolerance, time horizon, and financial goals. The signs are pointing toward a bountiful crop, even though we can’t predict the weather for the rest of the year.

1Source: PSC Research, March 2022

Twenty years ago, the role of the defined contribution plan sponsor was to help participants accumulate as much money as possible in their retirement plan. The participant’s role was to invest appropriately and be patient. Plan sponsors kept participants focused on maximum accumulation, while working behind the scenes to build a sound retirement plan that the average participant could rely on. Today, that’s no longer the case.

“It’s not just about accumulation or the typical participant anymore,” says Jennifer Doss, senior director of the defined contribution practice at CAPTRUST. “It’s about helping each individual plan participant with a decumulation strategy that meets their unique needs, so people are ready and able to draw a steady stream of income from their accumulated savings. It’s about personalization.”

Accordingly, Doss says her team has seen a swell in questions about how to leverage tools and resources related to the personalization of retirement income planning, including questions about retirement income services and products offered at many recordkeepers and asset managers.

Why is this subject top of mind for plan sponsors? “Participant trends are a big factor,” says Michael Sasso, principal and financial advisor on CAPTRUST’s institutional retirement plan team. “But also, recent technological advancements and innovative product development are starting to drive interest.”

Retirement Industry Trends

With most of the baby-boomer generation having already met the traditional retirement age of 65, the defined contribution industry continues to see net outflows in participant numbers and assets. Yet a higher percentage of plan participants are staying in plans after retirement.

In fact, the percentage of retiree participants has more than doubled in recent years. According to J.P. Morgan’s 2021 “Retirement by the Numbers,” the number of participants remaining in their DC plans three years after retirement was more than two times the same data set from only 10 years earlier—42 percent in 2021 versus 20 percent in 2009. These numbers show that more plan participants are using their retirement plans as investment vehicles after leaving the workforce.

“From the participants’ point of view, fiduciary oversight from the plan sponsor is a benefit to staying in plan after retirement,” says Sasso. “Plus, you’ll likely see lower investment management costs than what you are likely to acquire on your own, thanks to the buying power of the aggregate plan assets.”

At the same time participants are realizing the benefits of staying in plan post-retirement, employers are realizing how retiree participants can benefit the plan itself. “Plan sponsors are seeing better scale and better pricing power with vendors and investment managers when retirees keep their assets in the plan,” says Doss. “Retiree participants tend to have larger balances so preserving those amounts for longer benefits everyone.”

Why Personalize

Until recently, plan sponsors needed to focus on providing the best possible plan for the highest number of their participants. “They were putting the foundational pieces in place for the future of the industry,” says Doss, “but those building blocks were generic by necessity. Mass personalization just wasn’t possible.”

Now, technological advancements have improved the industry’s ability to customize each participant’s retirement experience. Those advancements have opened the door for plan sponsors to create holistic retirement income programs. “A few examples,” says Sasso, “are managed accounts that can now consider nine or more data points for defaulted participants—versus the prior one to three—plus advanced account aggregation abilities and withdrawal programs for people in the decumulation phase.” He also points to better retirement planning and projection tools that are now commonplace across the industry.

Another important trend: More employees now look to their employers for financial wellness and education. They want help both saving and investing well. “Plan sponsors are increasingly interested in learning what they can do to help participants customize their plans and turn accumulated savings into a somewhat predictable stream of retirement income,” says Sasso.

“As an industry, our mantra has historically been ‘get employees in the plan, get them saving enough, and get them invested well,’” says Doss. “Autoenrollment and qualified default investment alternatives (QDIAs) helped us make huge strides in those areas, but we’re still not doing enough for retirement income,” she says.

As behavioral economist Dr. Shlomo Benartzi explains on CAPTRUST’s “Revamping Retirement” podcast, “Right now, a lot of the tools and the guidance are really geared toward the two percent in [retirement plans] that have million plus.” A vocal advocate for automatic features like auto-enrollment, auto-escalation, and auto-invest QDIAs, still, Benartzi says, “I don’t think auto features [are] the right solution for decumulation. What’s the difference? I think the difference is that, over our lifespan, we do accumulate assets, but we also accumulate differences, which requires more personalization.”

Solutions and Tools

The best thing plan sponsors can do to support a personalized retirement income planning experience is pay attention to participants’ evolving needs. Ask questions, do research, and respond with plan features that meet those needs as they align with your overall employee benefits strategy. “Decumulation planning has to be personalized in order to be effective,” says Sasso, “because retirement income is too individualized to solve through product alone.”

His advice to plan sponsors: “Start by defining the goals and objectives for your plans, then work backwards into solutions.” In other words, start with the end in mind. Here are four solutions and tools plan sponsors should consider.

1. Education and Advice

Participants want consistent access to independent third-party advice, and financial wellness support. To meet that need, plan sponsors should tap the expertise of financial advisors, and take advantage of digital features. “Participants need help planning and investing to meet their unique goals for retirement,” says Sasso. “They need education, they need access to planning tools, and they need advice from independent experts who are genuinely invested in their success.”

Some topics plan sponsors might explore are budgeting in retirement, charitable giving, when and how to take Social Security, the benefits of staying in the plan after retirement, and how much to withdraw to meet specific goals. Plan sponsors should consider offering access to one-on-one guidance, small group sessions, or organization-wide education, depending on the needs of their business.

2. Withdrawal Options

It is increasingly rare for plan sponsors to offer only one lump-sum withdrawal option to participants. Instead, systematic withdrawals have become a standard offering from most recordkeepers. Digital tools from these recordkeepers allow participants to explore different withdrawal timelines and payment options, then implement and change their selections over time. Having options around how and when they can withdraw their assets encourages plan participants to stay in plan after retirement.

3. Guaranteed Options

Traditionally, conversations about retirement income have focused on annuities, and of course, annuities can be an important resource for participants who are in or nearing retirement. Especially for retirees, they provide valuable protection against market volatility. However, they can be costly and complex to implement and understand.

Some of the newer guaranteed investment products include the use of traditional in-plan annuities but offer more alternatives for customization around their use. They can now integrate with existing asset allocation programs or be offered as standalone options in a plan.

“If you learn that your participants are looking for pension-like income guarantees, you might want to consider these newer annuity options,” says Sasso. “They are currently the only retirement income solution that can meet that goal.”

Another option is out-of-plan annuity placement services, which allow individuals to withdraw and convert a portion of their retirement account balance into an annuity, while still providing access to institutional pricing. These out-of-plan annuity placement services can be a good option for plan sponsors that don’t want to offer annuities in-plan but want to give guaranteed access to participants.

4. Non-Guaranteed Options

Non-guaranteed investment options also have emerged to help plan participants create a steady stream of retirement income or achieve their income-focused objectives. This list includes target-date funds, income- or yield-focused strategies, and managed payout funds. Several fund companies also offer income-mandated strategies that focus on producing a specific annual yield.

One important piece to note is that these investment options can be used in combination with systematic withdrawals to further customize the participant investment experience while also establishing a reliable monthly income. “If it’s done well, it should feel like getting a monthly paycheck,” says Sasso.

5. Managed Accounts

Managed accounts are another useful tool for plan sponsors that want to provide a personalized decumulation experience, especially managed accounts that include individualized withdrawal advice and Social Security guidance. Although managed accounts were historically used only by high-net-worth individuals, technological advancements have democratized their use.

Today, the typical managed account will evaluate around a dozen data points for an individual participant and create a personalized portfolio designed to meet each person’s unique needs and desires regarding retirement income. These accounts can incorporate many of the tools described above, like systematic withdrawal services and in-plan guaranteed investment options. Although they should not be considered a silver bullet for personalization, when implemented as part of a retirement income program that includes one-on-one advice and financial wellness services, managed accounts can be an effective tool for plan sponsors.

Getting Started

Retirement income planning should be a holistic service, not a single product offering. To stay responsive to participant trends and take advantage of technological advancements, plan sponsors should consider changes to their DC plans to improve the after-retirement experience for participants and help ensure a smooth transition from accumulation to decumulation, as employees become retiree participants.

“Tools alone won’t solve the retirement income problem,” says Doss. “The key is understanding that tools must be accompanied by solutions and advice about how to use the tools. Also, not every participant will need or want to use the same tools, which is why a holistic approach to retirement income makes sense for plan sponsors.”

“To get started,” Doss says, “consult with your plan advisor and recordkeeper; these key partners can help you figure out which options are available and right for your participants and your unique organization.”

Thoughtful Dismissal of Fees Case by U.S. Court of Appeals: Process Prevails

In a thoughtful and thorough decision, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit has affirmed dismissal of a suit alleging overpayment of fees and improper use of actively managed funds. Smith v. CommonSpirit Health (6th Cir. 2022). CommonSpirit was sued alleging that:

- actively managed mutual funds should have been replaced with less expensive, better-performing, passively managed mutual funds,

- underperforming investments were imprudently retained,

- plan recordkeeping fees were too high, and

- investment expenses were too high.

We recently reported on Hughes v. Northwestern University, the Supreme Court decision that seemed to make it more difficult for plan fiduciaries to have fees cases dismissed. CommonSpirit is the first circuit court of appeals decision to analyze these issues since the Hughes decision was handed down.

The court in CommonSpirit grounded its decision in investment basics, noting the relatively recent advent of index funds, the range of investment options available, and the variety of investors who may prefer distinctly different types of investments. The judge provided a thorough review of bedrock principles that apply to plan fiduciaries as they carry out their duties and how their actions will be evaluated if called into question. He initially noted the context in which fiduciaries’ decisions are made, saying:

[W]hether the [fiduciary] is prudent in the doing of an act depends upon the circumstances as they reasonably appear to him at the time when he does the act and not at some subsequent time when his conduct is called in question.

In the last analysis, the circumstances facing an ERISA fiduciary will implicate difficult tradeoffs, and courts must give due regard to the range of reasonable judgments a fiduciary may make based on her experience and expertise.

In response to the argument that investors should be skeptical of an actively managed fund’s ability to outperform its index benchmark, the court noted that:

[Actively managed funds are] a common fixture of retirement plans, and there is nothing wrong with permitting employees to choose them in hopes of realizing above-average returns over the long life span of a retirement account…. It is possible indeed that denying employees the option of actively managed funds, especially for those eager to undertake more or less risk, would itself be imprudent.

The judge noted that, for a claim to survive a motion to dismiss, the allegations in the complaint must show that it is plausible that a breach occurred, not that it was merely possible or conceivable, saying:

[A] showing of imprudence [does not] come down to simply pointing to a fund with better performance.… In addition, these claims require evidence that an investment was imprudent from the moment the administrator selected it, that the investment became imprudent over time, or that the investment was otherwise clearly unsuitable for the goals of the fund based on ongoing performance…. [It is] largely a process-based inquiry.

This reinforces the importance of ongoing monitoring of investments and taking appropriate action. The plaintiffs alleged that comparative underperformance of 0.63 percent demonstrated imprudent retention of a fund. The judge challenged the plaintiffs’ use of five-year results as a primary basis for replacing a fund, saying:

Precipitously selling a well-constructed portfolio in response to disappointing short-term losses, as it happens, is one of the surest ways to frustrate the long-term growth of a retirement plan. Any other rule would mean that every actively managed fund with below-average results over the most recent five-year period would create a plausible ERISA violation.

Sustaining dismissal of the recordkeeping fees claim, the judge noted that the plaintiff failed to provide sufficient facts that could move the allegation from possibility to plausibility. There were no allegations that the fees paid were excessive relative to the services received.

The investment management fee was also dismissed because sufficient facts were not alleged. The judge observed that the plan offered investments with fees ranging from 0.02 percent to 0.82 percent, with an average fee of 0.55 percent. This range and the average were evidence that the plan included a variety of actively and passively managed funds. He concluded with the familiar statement that “Nothing in ERISA requires every fiduciary to scour the market to find and offer the cheapest possible fund (which might, of course, be plagued by other problems).”

This case is good news for plan fiduciaries. It is sure to be relied on as they defend the numerous suits filed in this area.

Have a Thoughtful Reason for Not Using the Least Expensive Share Class

About a month after its decision in CommonSpirit, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals addressed a claim not made in CommonSpirit and partially reinstated a fees case that had been dismissed by the district court. One allegation in the newer case was that the plan’s fiduciaries imprudently offered more expensive share classes when less expensive share classes of the same investment were available. The judge noted that different investments of the same strategy or type that are more or less expensive or perform better or worse are not reasonable comparators that allow a court to conclude that a claim is plausible. However, when the funds being compared are different share classes of the same fund, there is a fair comparison that can support a plausible claim.

The court was quick to point out that a variety of not-yet-known factors could “exonerate” the plan fiduciaries. This could include such things as revenue sharing that benefits the plan or limited eligibility for the less expensive share class. The case was sent back to the district court for further proceedings. Forman v. TriHealth, Inc. (6th Cir. 2022).

New Cybertheft Lawsuit Filed: $750,000 Missing … and Not Restored

Through a series of well-orchestrated steps, cyberthieves managed another theft of plan assets from a plan administered by Alight. A participant’s entire account balance of $751,431 was stolen, and Alight has not restored her account.

Paula Disberry worked as an executive for Colgate-Palmolive from 1993 to 2004 at various locations around the world and participated in Colgate-Palmolive’s 401(k) plan. From time to time she checked her account online and intended to leave it in place until she reached age 65. When she tried to check her account online in August 2020, she was unable to access her account because she had the incorrect username and password. She contacted the Colgate-Palmolive benefits department. In September 2020, when she was 52, she was informed that her entire account balance had been distributed to an individual with an address and bank account in Las Vegas, Nevada. Investigation of the theft revealed that: