Meanwhile, the prices of stocks and real estate have risen to new heights, thanks to the Federal Reserve’s easy money policies and government stimulus checks. Interest rates have ticked up slightly—from historical lows—further adding to inflation anxiety.

Zero Sum

Inflation is a complicated thing and, like most things macroeconomic, tends to be a zero-sum game—where one person wins only at the expense of causing someone else to lose.

Rising wages benefit workers—especially workers in industries hard hit by the pandemic and workers who have not seen meaningful wage increases in recent years. This, of course, means that consumers pay more for the goods and services they consume. Meanwhile, rising real estate prices are good for homeowners, but rising rents put pressure on renters’ household budgets. And rising interest rates generate more interest income for savers, but borrowers pay more on their mortgages, credit cards, and car loans.

Whether inflation is a good thing or a bad thing for you really depends on your specific facts. And the complexity of the equation for your household makes it difficult to predict the impact.

Times They Are A-Changin’

Over the past decade, interest rates have been stuck at historically low levels. In fact, along the way, fears of deflation and negative interest rates repeatedly made the headlines, and policy makers wondered what it would take to get back to a healthy level of inflation.

Along the way, investors, including many nearing or in retirement, struggled to generate income from their portfolios. They were forced to accept lower returns—at least on the fixed income portions of their portfolios—or take more risk to achieve their goals. Thankfully, those who took more risk by investing in stocks were handsomely rewarded (despite a few white-knuckle moments along the way).

Further, while the low-rate environment created income challenges for retirees, they benefited from low inflation during this period. So, even as they shifted to stocks and other riskier investments that generated higher returns, the cost of living barely budged, allowing standards of living to rise. According to Morningstar, a simple portfolio of 45 percent U.S. stocks, 15 percent international stocks, and 40 percent bonds, rebalanced quarterly (fees and taxes aside), would have returned more than 8.8 percent over the decade from 2011 to 2020 while inflation ticked up at a mere 1.73 percent.

Now, it seems that we are entering a new chapter. As inflation and interest rates creep higher, bonds and other fixed-income investments may, at some point, become more appealing. (This, of course, assumes we don’t see a rapid rise or a dramatic spike in rates.) That’s certainly good news for investors, but they should be careful to consider their financial plans before they make any hasty moves.

Out of the Frying Pan

As we sit on the verge of a potentially new and higher inflation regime, it’s important to understand two cognitive biases that become more relevant.

Money illusion is the name for a bias that describes humans’ tendency to think about their wealth and income in nominal dollars—today’s value—rather than real dollars that include the impact of inflation on tomorrow’s purchasing power. The money illusion anchors us to the value of money today and makes it hard for us to grasp, for example, what $100,000 of income will buy us in 10 years. At a 2 percent inflation rate that $100,000 will have only $83,400 of purchasing power in 2031. At 3 percent inflation, that number shrinks to $76,000.

Exponential–growth bias is our tendency undervalue the effects of compound interest. For investments, this means we tend to underestimate future values. For inflation, it means that we overestimate the value of our purchasing power of our savings. Because we are very bad at these calculations, our errors can be massive, especially over long periods of time or at high rates. And, of course, a financial plan for a couple age 65 retiring today should anticipate 30 years of income in retirement. That qualifies as a long period of time.

While these two biases may sound similar, they are recognized as separate behaviors, and, unchecked, they could lead to a big underestimation of the savings needed to fund long-term goals—or an overestimation of your future purchasing power.

One simple way to help overcome these biases and better understand inflation’s impact on your money is the rule of 72. Divide 72 by the annual inflation rate. The resulting number is how many years it will take to cut your purchasing power in half. For example, at a 3 percent sustained inflation rate, your purchasing power will be cut in half in 24 years compared to 41 years based on the 1.73 percent average inflation rate we experienced during the 10 years before the COVID-19 pandemic. That’s a pretty dramatic change for a relatively small inflation uptick.

A Change (Would Do You Good)

Thankfully, the creeping nature of inflation means that you have time to address the risks and plan accordingly. Here are a few tips to help make sure that your financial plan remains on solid ground, whatever the future might hold for inflation.

- Revisit your plan. It is wise to update your financial plan every three to five years—or more often in the event of a significant change to your financial picture or the market environment. Should we determine that the recent surge of inflation will stick around, you should contact your advisor to update your financials and rerun your plan to help ensure that it still makes sense.

- Do a shock test. As boxer Mike Tyson famously said, “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” Make sure your plan includes multiple scenarios, including extreme inflation scenarios, living to 100 (or older!), or a significant market sell-off during retirement—whatever you need to test to make sure you’re going to sleep at night.

- Reserve the right to reassess. Financial planning is not a set-it-and-forget-it endeavor. It’s an iterative process, and you can adapt along the way, as needed. If you determine that rising inflation creates risk for your plan, you may decide to work a few more years, save a little more, spend a little less, or accept the risk, knowing that you can take another look in a year or two.

At present, it is difficult to know how the recent rise in inflation will play out. We may just be experiencing a short-term bout of inflation. Or this may be the beginning of something longer-term. Perhaps we will encounter a mixed scenario, where we see sustained price increases in some areas of the economy while others abate.

Regardless, with a solid plan in place—and the ability to adjust, as needed, to conditions—you will be well on the road toward your long-term financial goals.

The U.S. Federal Reserve also took notice. Previously, the Fed’s comments on inflation risks emphasized patience. As the transitory effects of COVID-19 disruptions faded, declining inflation pressures would allow it to gradually taper monetary policy support, allowing time for the labor market to heal. But in its final meeting of the year, the Fed struck a very different tone as it acknowledged growing risks of longer-lasting inflation pressures and announced a more rapid conclusion of the bond-purchase program launched to support economic recovery in 2020.

While this abrupt pivot seemed to catch markets off guard, many consumers were far less surprised. They didn’t need a Bureau of Labor Statistics report to know that prices were on the rise. All it took was a trip to the supermarket, gas station, or car dealership to feel the sting of higher prices.

However, the extent to which any individual consumer or household felt the tangible impact of rising prices over the past year was driven by their unique pattern of consumption, and their sources of income. While a 6.8 percent CPI print will— very appropriately—grab its share of headlines, the true impact to any individual could be much more or far less.

Beyond the Headlines

Inflation is caused by too much cash chasing too few goods. This can be the result of a hot economy, where jobs are plentiful, wages are high and rising, and consumer sentiment is strong. It can also be caused by supply constraints, such as disruptions in energy markets, supply chain problems, or other interruptions in the normal flow of goods. Or—as was the case in 2021—it can be caused by both.

Over the past decade, price inflation within the U.S. economy has been remarkably tame, often failing to reach the 2 percent threshold considered healthy for economic stability and growth. Across an entire economy, the expectation for modestly higher prices tomorrow provides incentives for consumers to buy today, providing support for healthy consumer spending and demand.

While that’s the macroeconomic effect, inflation’s impact can vary considerably from consumer to consumer.

Those who owe money at fixed interest rates—such as mortgages and car loans—can benefit from inflation, as the burden of fixed payments is reduced over time. In contrast, those whose incomes are represented by fixed payments from savings, bond coupons, or pension payments can see their purchasing power fall.

In other words, the true impacts of inflation are highly personal. Ultimately, the presence of price inflation only affects those who choose to or are required to buy at the new, higher prices.

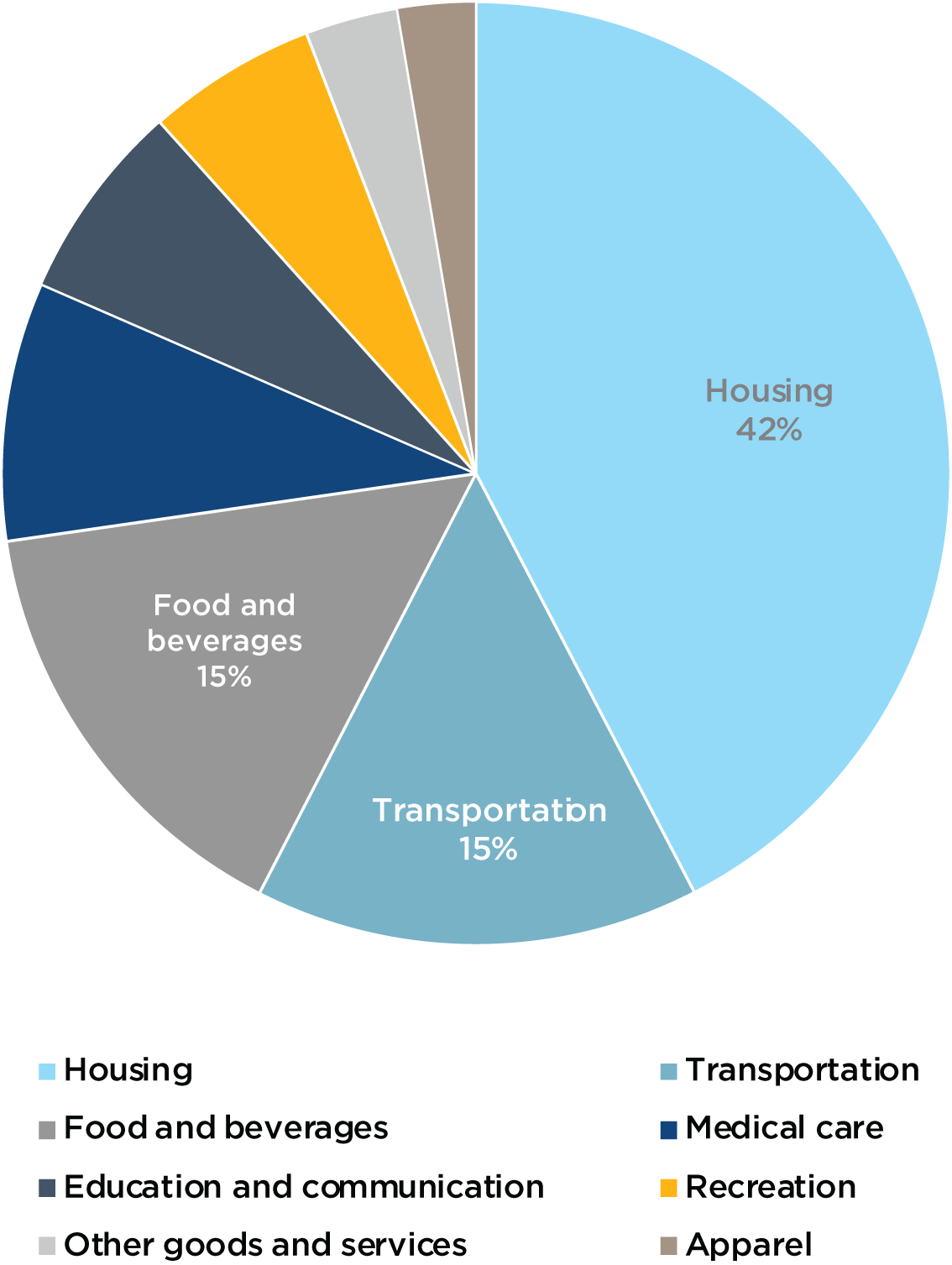

The fact that everyone’s experience with inflation is unique illustrates the challenge faced by economists as they attempt to gauge price conditions across an entire economy. The CPI is designed to reflect an abstract, average U.S. consumer across different geographies and categories of age, income, and other characteristics. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics accomplishes this with a market basket of expenditures created through tens of thousands of consumer surveys and detailed spending diaries each year. These expenditures represent more than 200 categories of goods and services, organized into eight major groups.

The basket of expenditures used to calculate CPI in 2021 was based upon expenditure survey data collected several years ago, in 2017 and 2018. And as shown in Figure One, housing, transportation, and food and beverages combine for nearly three-quarters of total expenditures, making the CPI measure (as well as the average consumer’s pocketbook) particularly sensitive to changes within these categories.

Figure One: CPI Expenditure Weights

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Often, changes in prices are spread unevenly across these categories of goods and services. This has been particularly true over the last two years as pandemic conditions radically altered consumer behavior and preferences, the production and distribution capacity for goods, and the ability to deliver services amid social distancing requirements. And depending upon where higher prices crop up, extreme price changes within a few categories can have an outsized influence on the overall level of the index.

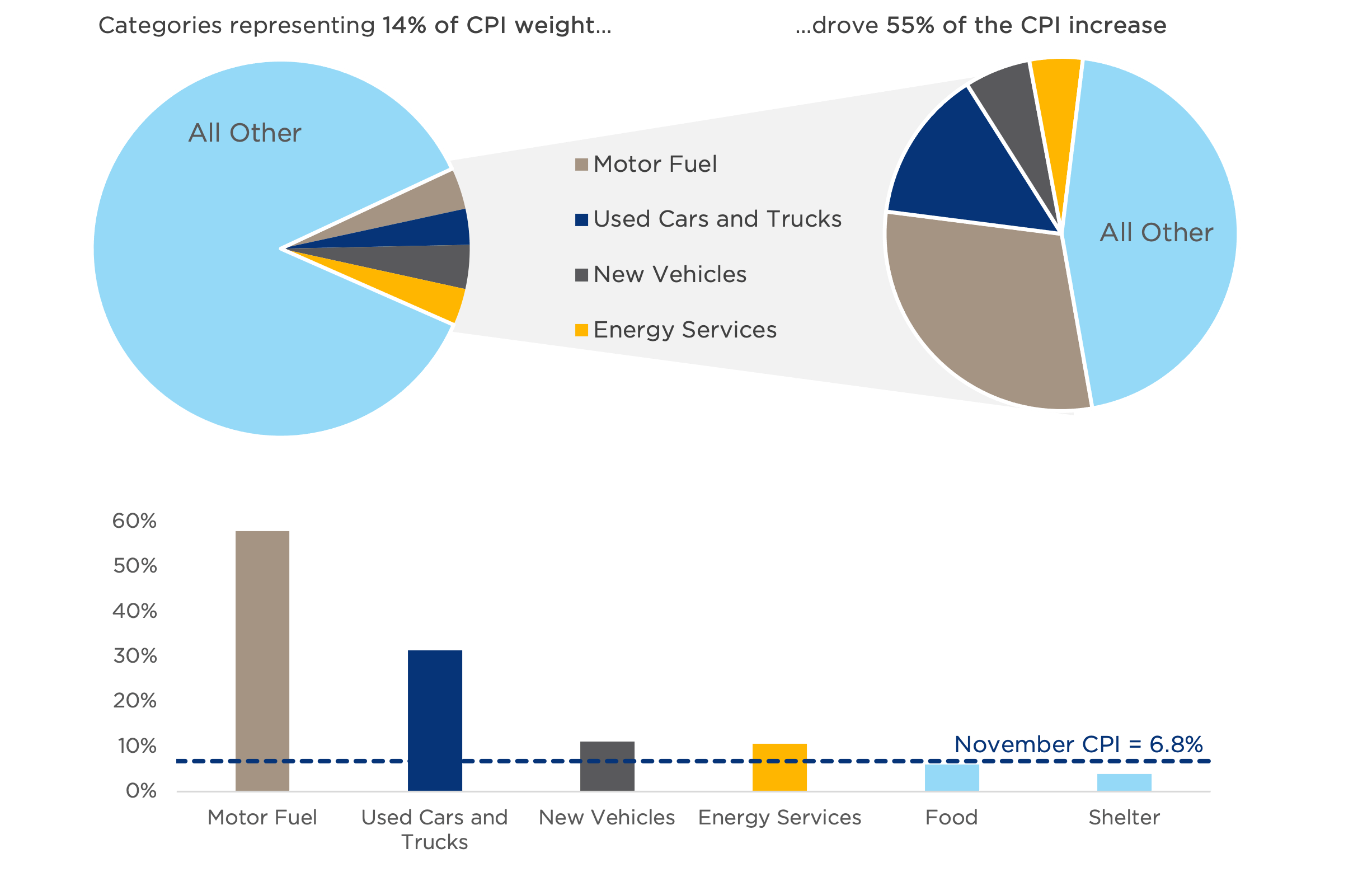

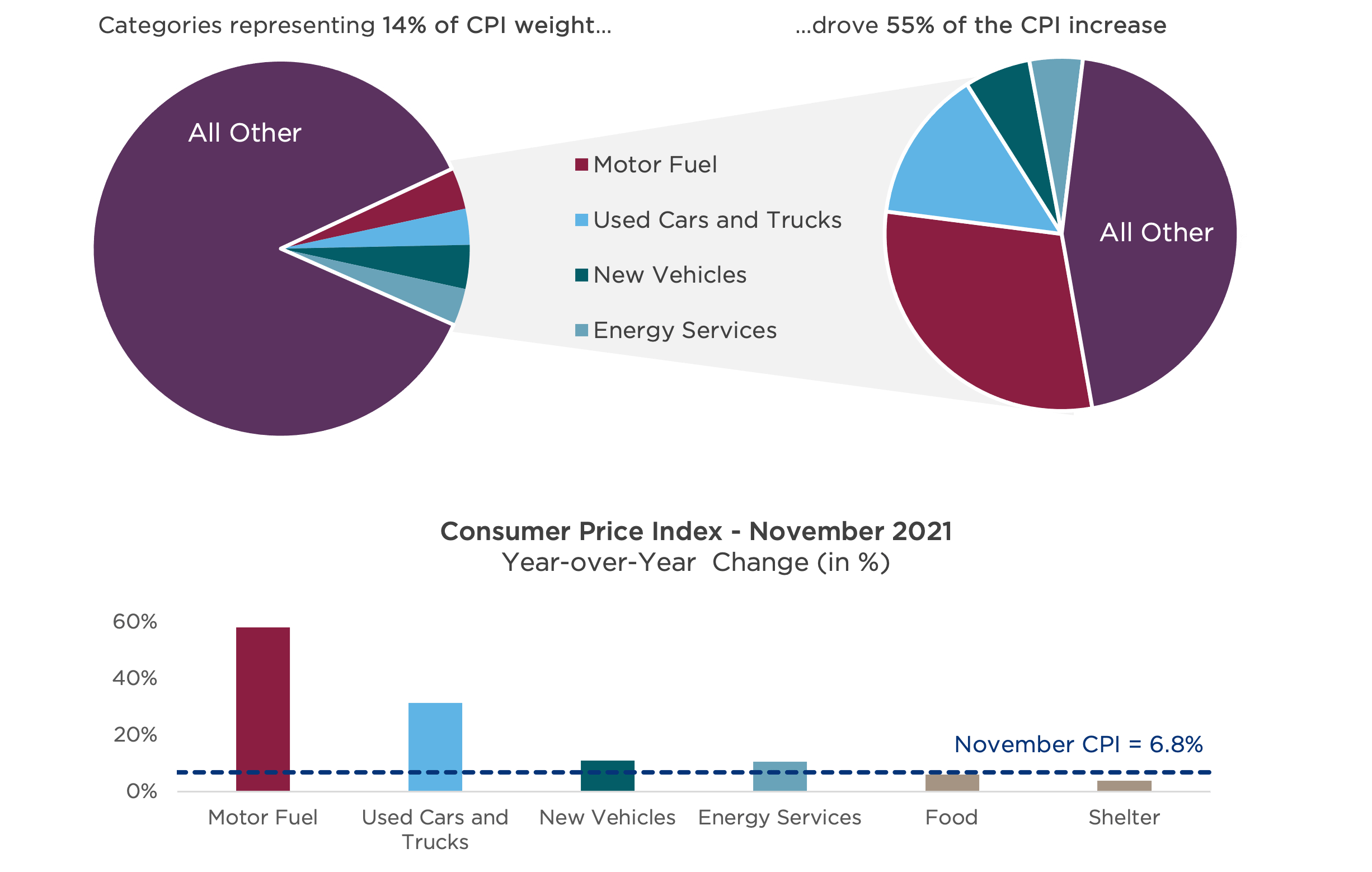

This effect played a major role in November’s CPI measure, as a relatively small subset of expenditure categories tightly linked to the economic reopening—such as fuel and energy—along with categories most affected by supply chain problems—such as autos—drove most of the year-over-year changes in CPI. As shown in Figure Two, the majority of the change in the November CPI was driven by a handful of categories, representing just 14 percent of total expenditures.

Figure Two: November CPI by Category

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Bloomberg, CAPTRUST Research. Selected categories, spending as a percentage of adjusted average annual expenditures (less cash contributions and personal insurance and pensions).

Weights and Measures

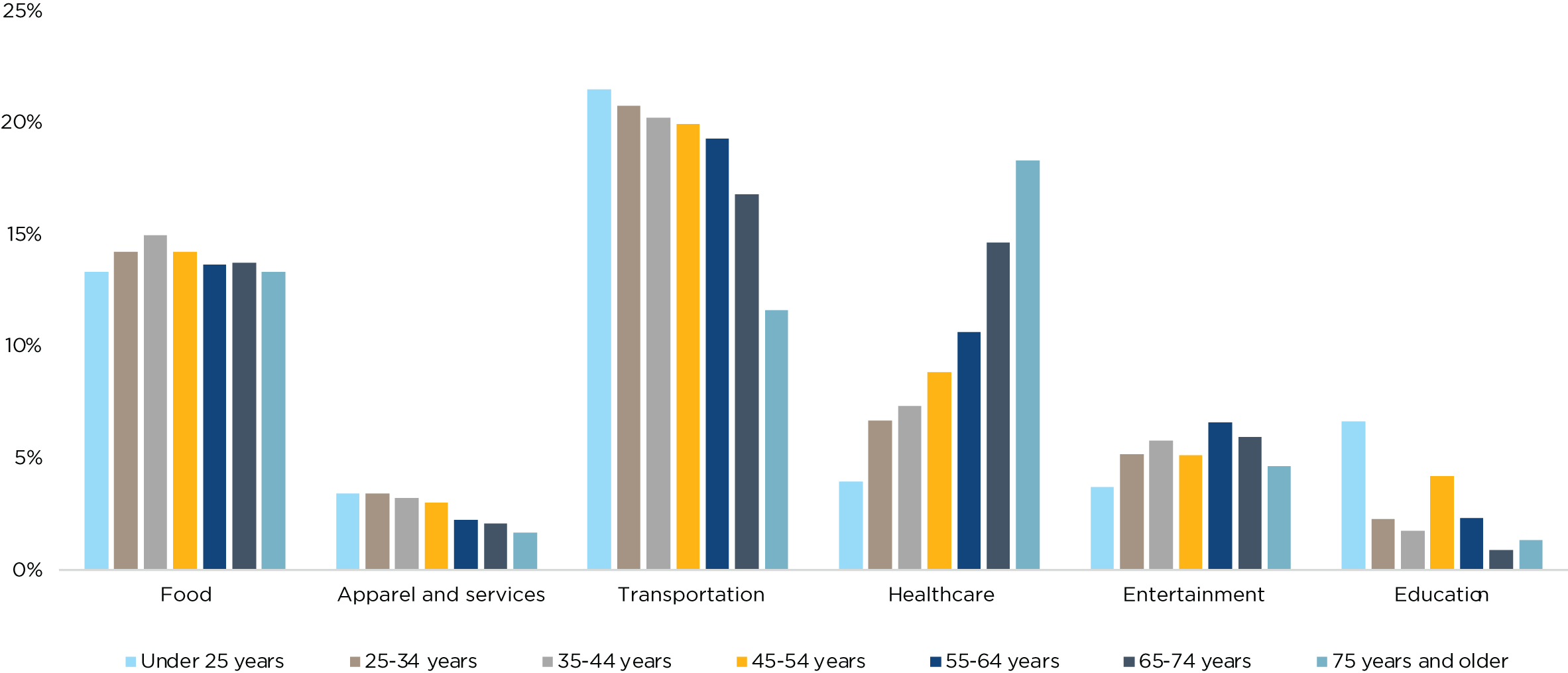

This uneven rise in prices seen over the past year means that different groups of consumers have felt the effects of inflation in very different ways. The dramatic rise in new and used car prices seen in 2021 was primarily felt by the consumers and businesses that needed to buy (or chose to sell) a vehicle. Likewise, expenditure patterns can vary considerably across age, income, and other household characteristics—differences that can be examined in detail with Consumer Expenditure Survey data.

For example, Figure Three summarizes the 2020 consumer expenditure survey results that break down average consumer spending as a percentage of adjusted average annual expenditures (less cash contributions, personal insurance, and pensions), across a range of age segments.

Figure Three: Spending by Category and Age

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (September 2021), CAPTRUST Research

As shown in Figure Three, some spending categories, such as food, don’t tend to vary much across age groups, while others—most notably health care, transportation, and education—can differ significantly. This means that price spikes within specific categories of goods and services can have an outsized impact on certain groups.

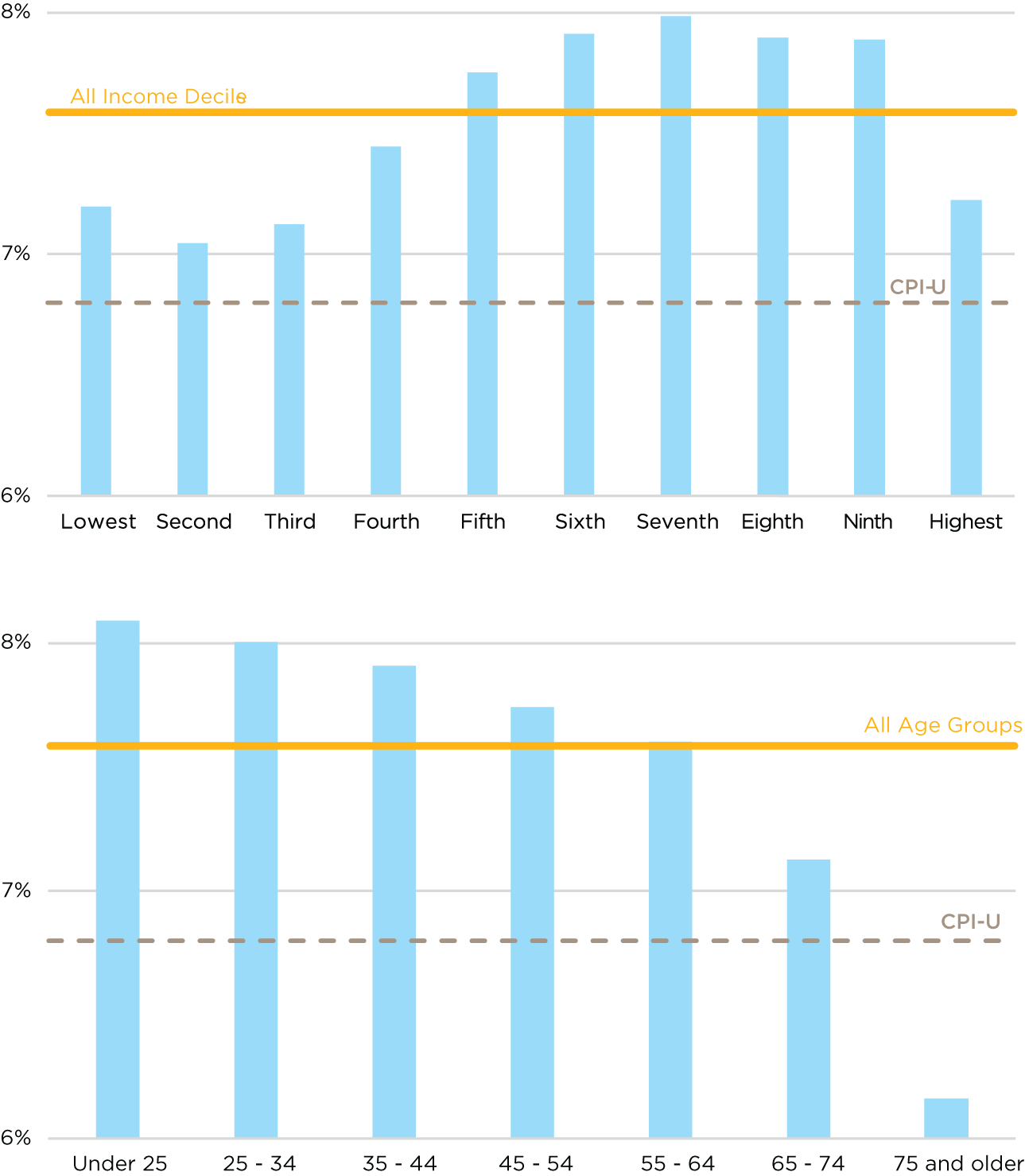

The availability of such detailed data on consumer expenditures allows us to adjust or reweight the November CPI data to illustrate the impact of inflation on different groups of consumers. Figure Four paints a picture of a very different inflation experience across different groups—even when limited to the broad brushes of age and income. When reweighted by differences in spending patterns, price pressures over the past year have been felt most acutely in households that are younger and within the middle- to high- income bands.

Figure Four: Reweighted November 2021 CPI, by Income Decile and Reweighted November 2021 by Age

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Expenditure Survey (September 2021), Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, CAPTRUST Research1

Note that reweighted CPI across all income and age groups of 7.6 percent differs from the November CPI reading of 6.8 percent. This difference is driven by differences in calculation weights due to the different time periods of the expenditure surveys, as well as differences in the populations surveyed (urban consumers for CPI vs. all consumers for the 2020 expenditure data).

Not surprisingly, the differences in inflation experience across groups is primarily driven by the degree to which each group is exposed to the categories (notably, transportation) that have experienced surprising price increases over the past year. Across income segments, the group with the largest share of transportation costs relative to income was the seventh decile, which includes those with 2020 before-tax income between roughly $76,000 and $96,000. When the November CPI results by category are applied to this group, their effective inflation jumps to nearly 8.5 percent.

Similarly, younger consumers tend to spend more of their paychecks on transportation costs relative to older cohorts. Given the complexion of inflation over the past year, this means that younger consumers may have felt the effects of higher prices the most.

The simple exercise above focuses on just one side of the ledger—expenditures—and does not reflect changes in income. If the wages for younger workers increased more than those of other groups, they may still be better off. However, it is still useful in thinking about which groups are more exposed to pockets of inflation as economic conditions change. If inflation pressures were to shift from transportation to health care, for example, as auto prices return to earth while the healthcare system continues to deal with lingering effects of the pandemic, then the inflation burden will likely shift toward older consumers.

But the key takeaway is that everyone’s consumption basket—and therefore their personal inflation experience—is a little different. Like any economic statistic, CPI is an abstraction of a system that’s far too complex to summarize with a single number, in the same way that no one would use the average daily temperature of the entire country to decide what to wear outside this morning. The experience in Phoenix and Anchorage will be very, very different.

Inflation and the Investor

As we move into 2022, there are reasons to believe that many of the inflation pressures described above will begin to ease as pandemic-altered consumption patterns and supply challenges continue to resolve. On the other hand, rising wages and rents may provide continued upward pressure on prices—and as illustrated earlier, changes across categories can affect different groups of people in very different ways.

But in addition to the inflation concerns of consumers are those of investors. Over the past year, one of the most common questions we’ve heard from investors of all types is: What can we do today to protect portfolios against inflation? As is so frequently the case with investment strategy, there is no silver bullet.

Part of the reason for this is a simple timing mismatch. By its very nature inflation is a long-term threat, which means it cannot be fully addressed with short-term tools. Some of the most commonly cited tools in the inflation toolkit— such as inflation-protected bonds, commodities, and gold—have shown an ability to react to short-term changes in inflation expectations but may also expose investors to other unintended risks or otherwise harm the total portfolio’s long-term return potential. Attempts at market timing often do more damage than good, and it can be shortsighted to reposition a portfolio for uncertain short-term risks at the expense of long-term success.

For long-term investors, the single best way to combat inflation is to seek to outgrow it via a diversified growth portfolio that is in line with their goals and risk tolerance.

But what investors can do today is think about what’s in their basket and how their consumption and income patterns are likely to change over time. In this way, inflation represents more of a planning problem than an investment problem, subject to a wide range of behavioral and cognitive biases, which, incidentally, are covered later in this issue. In his latest installment of Money Mindset, VESTED Editor-in-Chief John Curry explains the insidious effects inflation can have on our thinking and long-term financial plans—if you let them. “What’s So Bad About Inflation?” explains two cognitive biases that could lead to a big underestimation of the savings needed to fund long-term goals—or an overestimation of your future purchasing power.

1 Note that reweighted CPI across all income and age groups of 7.6% differs from the November CPI reading of 6.8%. This difference is driven by differences in calculation weights due to the different time periods of the expenditure surveys, as well as differences in the populations surveyed (urban consumers for CPI, vs. all consumers for the 2020 expenditure data).

Yet Alzheimer’s is the leading cause of dementia among older adults, with an estimated 6.2 million Americans currently suffering from it.1 A diagnosis has long seemed like a tragic one-way ticket down a sure path of cognitive decline, and for good reason: Alzheimer’s disease was incurable, untreatable, and believed to be unpreventable.

It isn’t anymore.

In addition to the first-ever Federal Drug Administration (FDA) approved drug that treats Alzheimer’s disease, ongoing research is proving that lifestyle changes within our control can go a long way in delaying or even preventing it.

“That’s the out-of-box thinking,” says John Walker, chief technology officer and founder of uMETHOD Health, a precision medicine start-up. “At every point in this, you can control the progression.”

A Multivariable Problem

Walker’s expertise lies in building complex systems to solve complicated problems, and Alzheimer’s disease might be the most tangled knot he’s taken on. According to Walker, there are 40 or 50 factors at play in causing the disease: genetics, history, blood chemistry, lifestyle—all interacting and confounding.

“This is a multivariable problem,” Walker says, “and the stinker is they interact with each other and they change.”

Between the ages of 65 and 75, 5 percent of people have Alzheimer’s disease. That number rises to nearly 14 percent as we age past 75. By the time we’re 85, more than a third of us will have the disease.2

It’s visible in our brains. Protein fragments of beta-amyloid clump into plaques outside our neurons while the abnormal form of the tau protein tangles up inside them. These and other changes can cause neurodegeneration, inflammation, shrinkage, and atrophy. The changes in our brains lead to changes in our lives, such as memory problems, impaired judgment, depression, and eventually physical impairment and death.

Walker’s company is figuring out which of the interacting, overlapping factors to prioritize when it comes to preventing and slowing disease progression. And his work, and encouraging recent clinical research, is showing for the first time that it’s possible.

An ongoing Finnish study known as FINGER was the first randomized controlled trial to prove that cognitive decline could be prevented through a combination of four lifestyle changes. And a modeling and meta-analysis published in The Lancet last year found that around 40 percent of worldwide dementias could theoretically be delayed or prevented. “It is never too early and never too late in the life course for dementia prevention,” the authors write.

Research has also revealed that we have a much longer window in which to treat the disease—which is present well before any cognitive impairment sets in.

“We know that Alzheimer’s starts 20 years, give or take, before the symptoms of dementia ever start,” explains Eric VanVlymen, a regional and executive director with the Alzheimer’s Association. “Dementia is really the end of a long process.”

The fact that Alzheimer’s begins decades before any mental decline means there is ample opportunity to address it before it causes problems, ideally even pushing the disease progression so far out that we succumb to other ailments before our cognition ever slips.

“A five-year delay in the onset of Alzheimer’s would cut the Alzheimer’s numbers in half,” VanVlymen says.

So how do we do that? What factors are under our control that we can change in order to prevent or slow the progression of this disease?

What You Can Do to Prevent Alzheimer’s

For those who already know they have Alzheimer’s disease, recent FDA approval of the drug Aduhelm offers a big dose of optimism. Though controversial for its accelerated approval and cost, Aduhelm is the first drug to actually slow disease progression. And since it is indicated for those who are not even showing cognitive impairment or have just begun to, it means people may be able to live with Alzheimer’s without ever developing dementia.

But the exciting news that lifestyle changes can slow the progression of Alzheimer’s means popping a pill is only one thing you can do to fight back. The actions you can take are not extreme. They’re not even surprising. “It’s everything your doctor always tells you,” says VanVlymen.

Findings from the FINGER study suggest four lifestyle approaches can help improve cognition among higher-risk elderly people.

First, keep your brain active. And sorry, but soduku might not cut it. “There’s a difference between brain activity and learning,” VanVlymen says. “Active learning is really important.” Second, you truly do have to get off the couch. Physical exercise—even something as simple as walking—is another critical to-do.

Third, research suggests eating a healthy diet is part of the answer. Diets clinically proven to combat cognitive decline are similar to the Mediterranean diet and the DASH diet, which minimize processed foods and encourage vegetables, nuts, berries, and legumes.

Finally, it’s critical to deal with cardiovascular risk factors like diabetes and high blood pressure. “The largest cardiovascular part of your system is your brain,” explains VanVlymen. “So, whatever is good for your heart is good for your brain.”

Because these four things were tested all together, researchers have yet to tease out what lifestyle changes pack the most punch. But taken with other research findings, there are plenty of things under our control that seem to matter.

“You actually have to sleep,” laughs Walker as he refers to a chart with dozens of factors at play in cognitive health. Avoid smoke and even air pollution if possible. Try to reduce your stress levels. And Walker says everyone should be asking their doctor for routine blood exams that check for the amino acid homocysteine; buildup can cause dementia, yet is easily treated with vitamins.

“It’s a brain toxin,” he says. “And it’s just a two-dollar blood test, but it appears that no doctors ever do it.”

Not that every fix is feasible. It might be easy enough to get help for sleep apnea or start a walking routine. But living next to a highway? That’s harder to fix. And since the past has a way of affecting your present health, comorbidities and medical history like previous head traumas or mid-life obesity will continue to influence your risk factors decades later.

The goal, says Walker, is finding out where you stand so you can get to work on the things you can influence. That’s something uMethod offers, and after working with about 5,000 people, Walker has seen this personalized approach to brain health pay off. “Doctors will tell you about their patients who just are quite astonished that they can come back in six months and say, ‘I feel so much better. I’m thinking better,’” he says.

The Future of Preventing and Treating Alzheimer’s

The Alzheimer’s Association and others are racing to figure out how lifestyle changes can slow the disease progression, digging down to isolate which activities are most protective, and combining the data with brain scans that will show whether those changes have observable effects on the brain.

In the next year or so, there will likely be approval for another two drugs to treat the disease, which VanVlymen hopes will create market pressure and drive prices down. “We’re going to be treating this disease with disease-modifying drugs that, frankly, we’ve never had,” he says.

At the same time, scanning for Alzheimer’s will get more accessible and cheaper—and therefore more equitable. And greater access to personalized medicine will help people know exactly what they can do to keep their brains healthy, and how their brains respond to treatments and changes.

The future of diagnosing and treating Alzheimer’s disease is full of hope. But when it comes to protecting ourselves and our loved ones, it is empowering to know we don’t have to wait.

1 Alzheimer’s Association, “Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures,” alz.org, 2021

2 Ibid

Since then, they’ve taken a 7,000-mile train trip, toured the country in their RV, and purchased a second home near their daughter, son-in-law, and three-year-old granddaughter. Their primary home, a 2,000-square-foot cabin in Blue Ridge, Georgia, is a step up from the vacation cabin they first moved to after selling their big family home in Atlanta.

Recently, they added a woodworking shop that doubles as a writing studio for Gilbert, who is the author of a blog, The Retirement Manifesto, and a book, Keys to a Successful Retirement: Staying Happy, Active, and Productive in Your Retired Years.

“We’re in the go-go years,” says Gilbert, 58. “We’re young, we’re healthy, we’re traveling. We are not worried. We are enjoying ourselves.”

Are the Gilberts crazy not to worry? Or are they on to something?

They are definitely on to something.

While many American retirees do indeed need to scrimp in order to keep paying their bills, many others have a nicer problem, financial researchers say.

If these well-funded retirees don’t start spending more of what they have, they may die with their nest eggs largely intact or expanded—even if they never consciously decided to do so.

While surviving family members, charities, or other beneficiaries may appreciate such sacrifices, there’s a price, says Sarah Asebedo, an assistant professor in the school of financial planning at Texas Tech University. “The downside is life not lived,” she says. “If you don’t pull the money out, if you don’t spend it, what are you missing out on? What are you holding back on? What are you giving up?”

The things you could miss out on—from travel to family time to doing good works—are exactly the things you probably saved for in the first place, she and other experts say.

The Retirement Consumption Gap

In the dry lingo of academia, this underspending problem is called the retirement consumption gap. It’s unclear how common this somewhat enviable affliction is. But recent research provides some clues.

One study published in 2021 in the Journal of Financial Planning found that just 18 percent of newly retired Americans had enough wealth to keep spending at preretirement levels. But a funny thing happened as people settled into retirement.

Almost everyone, at every wealth level, spent less. In most cases, this was a good move, a matter of right-sizing spending to fit available resources, co-authors David Blanchett and Warren Cormier reported. They found that 10 years into retirement, 48 percent of households had the resources to support their spending.

But because well-funded households typically cut back on spending, as well, many actually spend much less than they could afford.

“We see too many households err on the side of not spending when they’re younger in retirement” for fear of running out of money when they are older, says Blanchett, who is managing director and head of retirement research for PGIM DC Solutions, the global investment management business of Prudential Financial.

Another study, also published in the Journal of Financial Planning in 2021, found that average retirees in the top three-fifths of income spent less than they took in from Social Security, pensions, investment earnings, and other income sources. The researchers, led by Asebedo’s Texas Tech colleague Christopher Browning, then looked at how that consumption gap might affect overall assets over a 30-year retirement under various investment scenarios.

Their conclusion? Even if a generous 40 percent of the portfolio was set aside for late-in-life medical expenses and bequests, a retiree with a mid-level income might underspend by as much as 8 percent. The wealthiest retirees might use 47 percent less than they could safely spend.

“Retirees in the top quintile of financial wealth were spending nowhere near an amount that would place them in danger of running out of money,” the researchers concluded.

Understanding the Underspending Mindset

Mike Gray, a CAPTRUST financial advisor based in Raleigh, North Carolina, says he sees plenty of people who haven’t saved and invested nearly enough to keep up their spending in retirement. These folks may have enjoyed six-figure incomes, nice homes, pricey vacations, and other trappings of a comfortable lifestyle, but they never saved more than the bare minimum in a 401(k) plan. Many are unpleasantly surprised to learn that they must live more modestly in retirement, he says.

But Gray also sees plenty of potential under-spenders among diligent lifelong savers. For example, take a couple who have $3 million in retirement accounts and are used to living well within their means, Gray says. “If spending doesn’t change during retirement at all, and they don’t do any travel or anything outside the realm of their normal budget, what ends up happening is that their asset base grows year after year after year until they pass away.”

All of a sudden $3 million is $12 million, Gray says. “You show them that and say, ‘OK, what do you want to have happen with this?’ And their eyes kind of go wide and they say, ‘Oh, wow, I never thought about that.’”

But nudging people to spend more isn’t a simple matter of showing them an eye-popping projection. That’s because good savers often have personality traits that make them uneasy spenders, Asebedo says. In one study, she and Browning found some of the lowest portfolio withdrawal rates among people who showed the highest levels of conscientiousness.

“These are the quintessential savers, the budgeters, the ones who have all the checklists,” she says.

Spending more may literally make such people queasy, Asebedo says.

“We expect people to just flip a switch once they get to retirement. We say, ‘OK, it’s time to take money out, it’s time to spend.’ And I think we underestimate what kind of a psychological leap that can be for a lot of people because of the years and years of blood, sweat, and tears and self-control it took to put that money in. It actually can feel painful and nauseating for some people to pull money out.”

Blanchett agrees. “People spend all these years socking away money … then all of the sudden to change that mindset from ‘save, save, save’ to ‘spend, spend, spend,’ that’s just not easy.” He says many people envision their portfolios as “this gigantic pot of money” that must be protected because it can never be replaced.

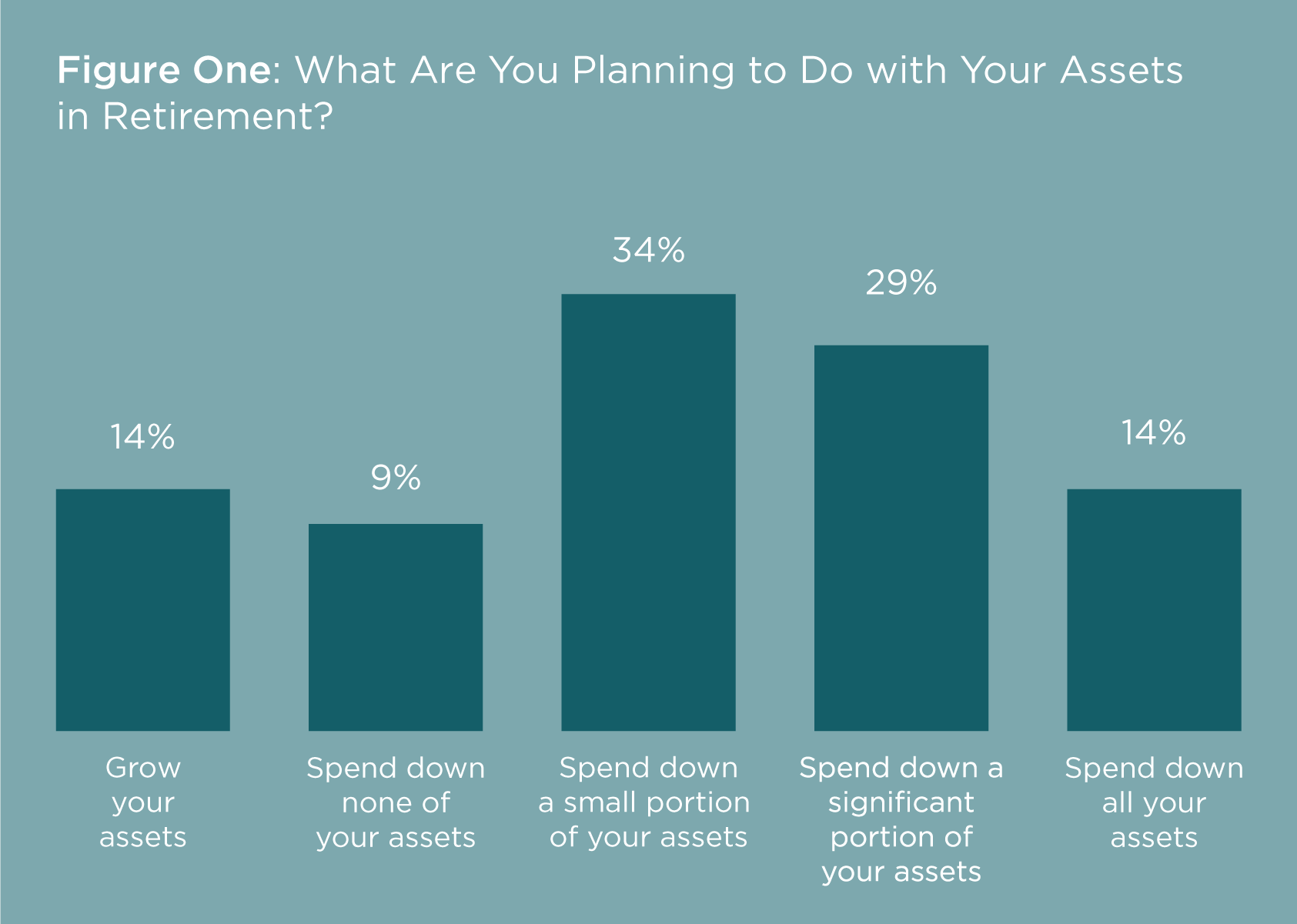

In fact, according to a September 2020 Employee Benefit Research Institute survey of 2,000 Americans ages 62 to 75, only 14.1 percent think they’ll spend down all their assets. Moreover, as shown in Figure One, nearly 60 percent plan to grow their assets in retirement, leave them untouched, or spend them down only a little.

Source: Employee Benefit Research Institute

The objections to spending go beyond gut feelings, of course. People who retire at 60 or 65 are worried about their healthcare needs if they live to be 90 or 95. Or they are worried they may need to financially support an aging parent or a struggling adult child. Some are highly motivated to leave large sums to their children, though Gray says such folks are in a distinct minority. Some have other bequests in mind. Many are worried about maintaining their lifestyles if markets tank in the future.

The secret to loosening the purse strings without losing peace of mind? It’s all about planning.

Enjoying the Well-Planned Retirement

Allen Chamberlain, a retired schoolteacher and librarian from Richmond, Virginia, might seem like the sort of person who would have trouble spending her retirement savings.

Chamberlain, 68, says she grew up with parents who “were pretty remarkable savers, even though they were not high income.” She tried to follow in their footsteps during her working years, contributing as much as she could to her retirement plan and sticking to a conservative but effective investment strategy. She also received an inheritance from her thrifty parents.

Before she retired at age 65, she worked with her financial advisors, including Gray, to come up with a plan for making her money last. “I came up with a budget of what was really necessary and what was important to me, and that helped me see what was possible,” she says.

Under her plan, she gets a monthly income from her portfolio that goes straight into her checking account. With that income, along with Social Security, she says she lives a comfortable but not extravagant life.

One luxury she allows herself and has budgeted for is regular extended trips overseas to visit her grown daughter, Evie, who lived for several years in Edinburgh, Scotland, and now lives in Zurich, Switzerland.

Chamberlain says her planning also allows for flexibility. She says that when she wanted to withdraw $30,000 to renovate two bathrooms in the home she shares with her partner of 31 years, she checked with her CAPTRUST advisors.

They reassured her that the expense would not throw her long-term plans off track or force her to cut corners. “They were able to assure me that ‘you’ve got this,’ because of the careful planning in place.”

Planning is also the secret to the Gilberts’ active lifestyle. Before he retired, Fritz Gilbert says he and his wife decided they could safely withdraw 3.3 percent each year from their portfolio. That’s in the conservative range recently endorsed by some financial forecasters worried about future market downturns, Gilbert notes.

His plan also includes spending less in later years when healthcare costs typically rise but other wants and needs tend to decline. The Gilberts also plan to leave a pool of money available in case either of them needs costly long-term care.

“You’ll never alleviate all the risks, but you do what you can to alleviate the most likely risks,” Gilbert says.

And then, he says, you live your life and, ideally, think very little about money. Like Chamberlain, Gilbert has a paycheck sent monthly to his checking account. And that money, he says, is money he feels very comfortable spending.

On a typical day at home, he is exercising, writing, or building something in his workshop. His wife is busy running a nonprofit called Freedom for Fido that provides doghouses and fences to families that would otherwise leave their dogs on chains.

One week a month, they load up their own four dogs and head to their condo in Alabama to spend time with their daughter and her family. When money builds up in their checking account, they spend and enjoy it—because, Gilbert says, that’s why they saved it in the first place.

“We are not recklessly optimistic,” he says. “But we live optimistically.”

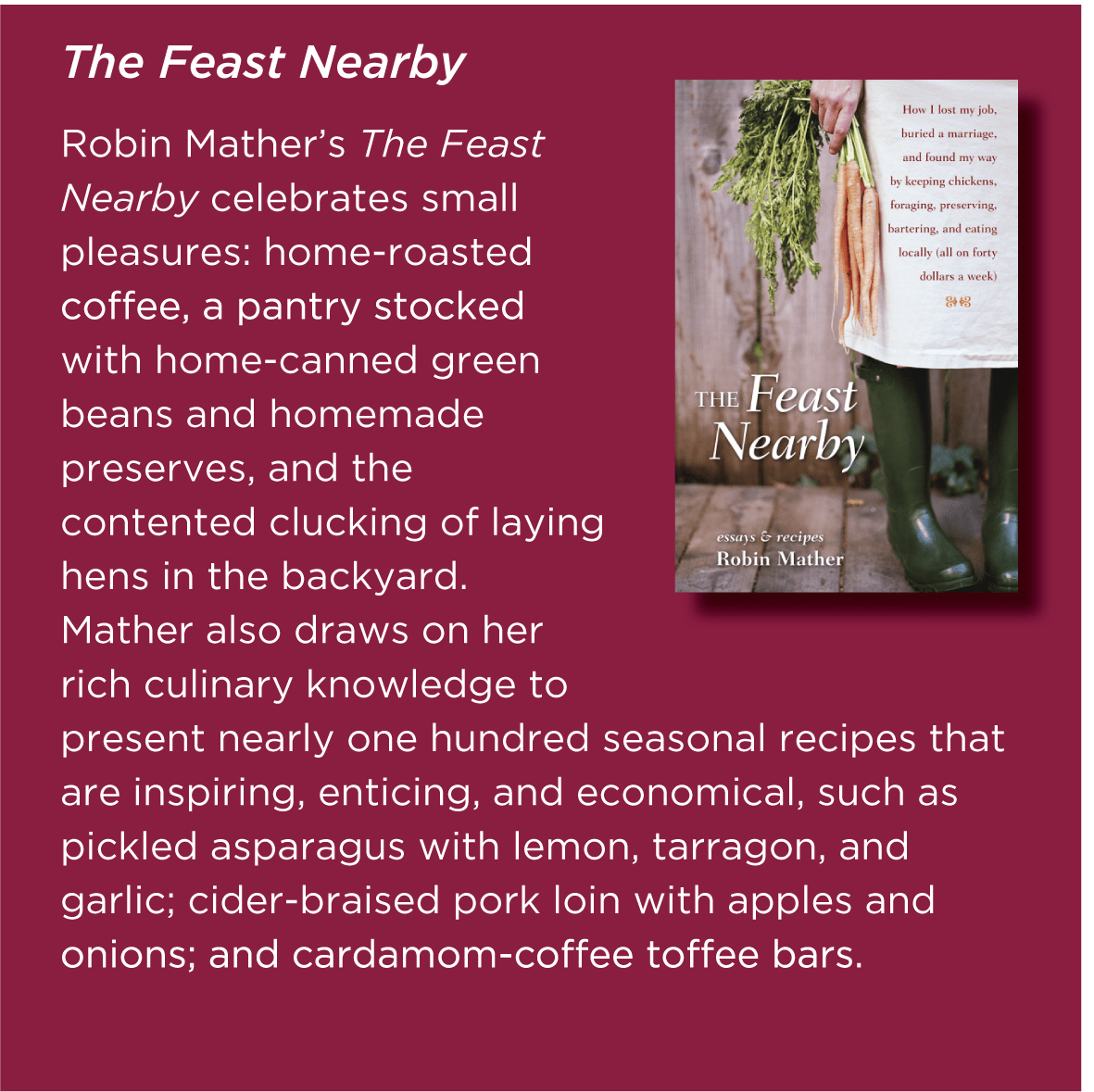

“Food is a key that unlocks everything,” says Robin Mather, a food writer for more than 40 years and author of The Feast Nearby.

“It unlocks the cultures of our neighbors, it unlocks our own history, and it unlocks the history around the world,” Mather says, whose forebears came from Wales to work in the coal mines in Iowa. When she makes Welsh cakes (similar to scones) or cawl (a kind of lamb soup), Mather says she thinks about her family’s journey.

Marcela Curry, of Raleigh, North Carolina, agrees that food is a way to maintain a link to your home and culture.

“For me, because I am an immigrant to this country, it’s a way to stay connected to where I’m from and a great way to stay connected to who I am,” the native of Chile says. “As I’ve gotten older, it’s interesting how being an immigrant has become more important to me,” Curry says.

Adapting to Change

The traditional foods you grew up eating might not be quite the same here as those your family prepared in its country of origin. Don’t be disappointed if you can’t replicate a traditional dish exactly as you had it there.

“Recipes for traditional foods are living things that evolve over time,” Mather says. “You see that in a lot of Italian recipes.” Some of the ingredients they were working with just weren’t available in the U.S., Mather says. For example, mortadella (a cold cut meat mixture) and sausages were nowhere to be found. “The Italian immigrants had to improvise on the spot.”

That would also be true for many African and Asian people, Mather says, who couldn’t find the fruits and vegetables they were familiar with when they came to this country. They had to alter traditional dishes, while others had to change recipes to keep costs down.

“When I was the food editor at The Detroit News, I had a colleague whose grandparents emigrated from Armenia, and as a teen, he lost his mother to breast cancer,” Mather says. “He was desperate to create his mother’s recipe for kibbeh (spiced grain and meat shaped into balls).”

One day, she says, he burst into her office and said, “‘I got it, I got it! I figured it out!’” What he discovered was that his mother couldn’t afford the traditional ground lamb, so she used a mixture of three-quarters ground beef and one-quarter ground lamb. “That was the taste he remembered,” Mather says.

Another consideration is that ingredients might be the same, but the flavor of the dish will be different, Curry says. “Chile is mountainous; volcanic soil is everywhere. The flavors of food are going to be different,” she says. “A cup of milk in the U.S. will taste very different from a cup of milk in Chile,” Curry says.

Beef and pork might have a different taste because of the way the animals were raised and what they were fed. “If you go to the southern part of Chile and you have lamb, you will remember it,” Curry says. “The flavor and the smell of lamb when it’s cooked there is sweet; it’s just divine.”

Explore from Home

If you’re not able to travel, food is the best way to start learning about another culture or country, Curry says.

“I had to teach myself to eat spicy food because I had never had it.” When she got to the U.S., because she spoke Spanish, when Curry went to a Mexican restaurant, people assumed that she knew the food, she says. “I had never had Mexican food before, so I had no idea what the menu was about,” Curry says. “But being exposed to Mexican food made me think, ‘Wow, the world is full of interesting stuff. What other kinds of foods are out there?’”

Exploring cultures through specialty cookbooks is one way to start. However, if you want to prepare a traditional dish, the recipe might call for ingredients that aren’t available locally. Mather recommends turning to online vendors such as Penzeys Spices and The Spice House.

Curry advises checking your television listings.

“On Netflix, Taco Chronicles walks you through the food culture of Mexico.” It’s a fascinating way to learn about Mexican culture, Curry says. “A taco is not just a taco; the filling represents the food that is being grown in that region in Mexico.” TV is rife with shows about food from all corners of the world today: British baking, Asian street food, Mexican asado, and more.

Local festivals are also a good way to explore a culture through cuisine. For example, where Mather lives in Arizona, there is the Tucson Meet Yourself festival. Other local resources you might find helpful could include ethnic and international grocery stores, specialty street markets and food stalls, cooking classes, cultural centers, and neighborhood churches.

Travel to the Source

“If money is no object, I would travel to a place where I could sign up for a series of cooking classes,” Mather says. “Working with someone in the country of your heritage, you’ll get a clear idea of how that food fits into your culture.”

Curry enjoys exploring food when she travels. “I just go and salivate walking through the markets. I’m drawn to the smells when I walk by, and I have discovered some absolutely amazing things,” she says.

If you’re planning a trip, she advises doing a little culinary homework before you go. “Do the research, and it’s not that difficult to figure out what good food is really all about,” Curry says.

And she practices what she preaches. “When I travel for work, I’m notorious for disappearing, and you will find me at a restaurant, hopefully a Chilean or other Latin American restaurant,” Curry says. “The more styles of food you try, the more you understand how your food culture connects to others.”

Making Connections

Food can also be a way to tell your children about family history. Mather advises cooking with kids while telling stories about your parents and grandparents. Talk about the history of the dish, where it originated, and where it’s eaten today. Host a potluck for family, friends, or community and have each person bring a special dish to celebrate their culture. Or use a holiday, birthday, or the anniversary of a loved one’s passing to celebrate their life with a special meal.

Curry says families frequently share their histories and cultures with their communities through food. “Food is a great way to transfer knowledge from one generation to the next and a great way to expose friends to another side of your personality.”

Curry celebrates Chilean Independence Day with her family and friends by making empanadas (baked meat pies) and ensalada chilena (a salad with tomatoes and onions) served with wine from the South American country. Her empanadas have inspired more than one person to visit her homeland.

Go backward, but also sideways and forward, Mather advises. Are you getting to know your own background? Your neighbor’s background? A culture in which you have an interest? No matter what, food is the key that will open any door.

“Whatever your heritage is, eating the foods of that culture can help you connect to that heritage,” Mather says. “And if you’re fortunate enough to have memories of a person who emigrated, it will help you remember that person, as well.”

At the age of 39, Entin suffered a massive stroke. Since then, he has been fighting his way back—not only to rebuild his body, but to launch a second act helping other stroke survivors.

“God wanted me to take a new journey, a new path. I call it a stroke of luck,” says Entin, 49, of Tarzana, California.

Go, Go, Go

Entin’s drive to create new businesses started early. At age 21, while earning a degree in business administration and management with an emphasis on entrepreneurship, he was featured on the cover of the business section of the Los Angeles Times for launching a teen dance club.

After graduation from the University of Southern California, he produced feature films, commercials, music videos, and a television show. He became one of the first fight managers in the mixed martial arts world, representing big names in the field, such as Mark Kerr and Tim Sylvia.

Later, he moved from Los Angeles to San Diego to work with two start-up companies, collaborating with basketball legend Shaquille O’Neal.

“I was raising money, building my companies, all the time looking for something new,” Entin says. “I was always connecting people. I was wound up too fast and too hard. I was go, go, go. I didn’t slow down, and something was bound to happen.”

By age 39, Entin was on top of the world. He lived on the beach in San Diego with his wife and two daughters, then ages 18 months and four years. “I love being a dad,” he says. “I was born to be a father. We were always off to the beach, the zoo, Sea World.”

Like a Sledgehammer

By this time, Entin was involved with teaching entrepreneurship skills to Navy SEAL veterans. He also trained with them in mixed martial arts. “I loved the sport. I loved athleticism,” he says. But in the fall of 2011, when Entin was doing a mixed martial arts workout, he got choked out.

“I passed out and wasn’t able to tap out,” Entin says. He went home that afternoon knowing something was wrong with his throat.

For about four weeks after the incident, Entin continued to run his business and jet around the country despite the pain on the right side of his throat. On Thanksgiving weekend, he and his family were celebrating the holiday with friends in San Luis Obispo, California, when things got worse.

“I woke up the night of Thanksgiving, and the room was spinning,” Entin says. “It felt like someone was bringing a sledgehammer to my head.”

He walked to the bathroom. “As I looked in the mirror, the left side of my face was drooping badly. My face was ash gray,” Entin says. “I couldn’t speak, and I lost movement in my left arm.” At that moment he asked his wife, Stephanie, to call his dad, a retired medical doctor in Tarzana.

“I think my son is having a stroke,” Dr. Allen Entin said. “Call the paramedics right now.”

Entin was rushed to a nearby hospital, then medevacked to Santa Barbara Cottage Hospital, where Alois Zauner, a top neurosurgeon, began treating him.

After several procedures didn’t work, Entin was put in a coma for 10 days. Then the surgeon performed a craniectomy and temporarily stored a piece of his skull in his abdomen to reduce the swelling on his brain.

When Entin awoke from the coma, his father told him he was a paraplegic, paralyzed on his left side.

“I couldn’t stand up. I couldn’t walk,” Entin says. “I had a helmet on my head to protect my brain. I had a feeding tube. I had a peripherally inserted central catheter line going from my arm into my heart, and I had a scar on my head shaped like a horseshoe.” He was also frail, having dropped from a fit 175 pounds to 140.

I Can, I Shall, I Will

Entin was taken for inpatient neurorehabilitation at a hospital near his home in San Diego. “The first neuropsychiatrist who got a hold of me ran a couple of quick tests, and she said, ‘The right side of your brain is dead. Don’t think about driving, working, or walking for a long time.’”

He fired her.

Then he brought in a team of people who believed in him and adopted his new mantra: I can. I shall. I will. “I kept saying to myself every day, ‘Put yourself in the mindset that you can do anything and nothing is impossible.’ I knew if I kept moving,” Entin says, “I was going to keep improving.”

What motivated him the most was the thought of not being able to hold, hug, or kiss his daughters. Entin says the greatest joy of his life comes from spending time with Savannah, now 14, and Shiloh, who is 11. “They are my why. My daughters are the reason I wanted to walk again, not sit in a wheelchair.”

So, he worked from early morning until the evening, even calling in medical professionals on the weekends. “I called it my boot camp,” Entin says. “I couldn’t even sit up straight. I lost the whole left side of my body from my vision to hearing to swallowing to walking. I had to relearn to walk, dress, shower, and use the toilet.”

After his stint in rehab, he went back home, but it was too hard on his wife to take care of two young children and him, so Entin moved back in with his parents in Tarzana. “I needed to heal. I needed to do my therapies,” he says.

Of course, there were days and moments when he wanted to give up.

“The physical side is painful. But the emotional trauma and the mental anguish was harder than the physical stuff at times,” Entin says. His rehabilitation took a toll on the people he loved—his parents, his family, friends, and his marriage, which ended in divorce. “Everybody felt so helpless, so angry, and so exhausted because they didn’t know what to do for me.”

A sense of humor helps, he says: “Humor heals, but it takes time to get through the pain, the sorrow, the depression, and the darkness.” Once you get through that, he says, your light shines brightly on everybody.

Transforming Lives

About 800,000 Americans suffer a stroke each year, and approximately two-thirds of these individuals survive and require rehabilitation, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Many survivors can have prolonged recovery and some are left with residual neurological deficits. In fact, complete recovery can take months or even years.

That is why, in 2018, Entin founded strokehacker.com and the associated Stroke Hacker Community, with one simple goal in mind: helping others hack their strokes or traumatic brain injuries (TBIs).

His work includes one-on-one coaching, encouraging survivors to face new challenges in their lives and helping them begin to plan a recovery road map.

When Entin is not doing national TV appearances or podcasts to tell people what’s possible with a resilient attitude, he works with the families of survivors.

“You have to get the people around the traumatic survivors involved,” Entin says. His neurologist, S. Thomas (Tom) Carmichael, chair of the Department of Neurology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, agrees. “Survivors need a team of supporters,” Carmichael says. “They need a network of people who will help them recover, and they need a process.”

In addition to strokehacker.com, Entin has created Move 2 Improve, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit foundation working on rehabilitating those who have suffered TBIs. Between his endeavors with the nonprofit and strokehacker.com, Entin’s goal is to help transform the lives of 1 million people overcoming any kind of traumatic injury—whether it’s a stroke or spinal cord injury—by 2030.

“Sean is an enormous force for good for those around him,” Carmichael says. “He sees the good in people and brings out the best in them, urging them on to further achievement.”

Entin never gives up, says Gloria Rios, his athletic trainer for the past five years and co-founder of the Stroke Hacker Community. “He always has hope, even when he’s down,” Rios says. “The one thing he didn’t lose through his stroke is his drive to excel and continue to look out for other people.”

Entin does rehabilitation three times a week and is seeing improvements. But the signs of stroke are noticeable. “My left arm is still weak, my left fingers don’t work as well as they should, and I walk with a limp,” he says.

However, he is not angry about what happened to him.

“This was God’s way of me becoming someone new and better,” Entin says. “My stroke gave me a deeper understanding of kindness and compassion and most importantly, allowed me a chance to make a difference for others.”

The Stroke Hacker

Recognized as a thought leader and speaker in the stroke survivor community, Entin is helping survivors and those around them find new ways to work through challenges, break through plateaus, and begin planning their recovery based on tailored advice.

The Stroke Hacker methodology uses a simple, yet powerful approach.

Ask the important questions. What is your current situation and what do you want to achieve? What is your perspective on your situation, and how does that need to change to get there? What are you doing to accomplish your goals, and what behaviors do you need to change?

Assess opportunities. Each stroke survivor’s situation is unique and so are the opportunities available to them. With the support of the Stroke Hacker Community, those overcoming TBIs will have an expert in their corner to help them navigate the host of offerings and opportunities, such as modified therapies to best serve individual needs and custom planning to get them closer to recovery and independence.

Work together to achieve the unbelievable. Overcome difficulties and achieve a new reality with a shared commitment and accountability. Your success is Stroke Hacker’s success.

For those who have suffered brain injuries, the Stroke Hacker Community is a place to share stories, accomplishments, and tips for improving overall health and wellness after a TBI. Subscribe at strokehacker.com to start receiving tips and insights into TBI recovery, or visit Stroke Hacker on social media.

If 2021 could be summarized in one word, it would be dichotomy—the sharp contrast between our financial lives and our daily living. The fourth quarter capped off a year that witnessed robust growth of all kinds, including both positive examples, such as rising home and financial asset prices, levels of household wealth, corporate earnings and profits, and wages, along with a troublesome rise in areas such as virus case counts, order backlogs and delays, and price inflation.

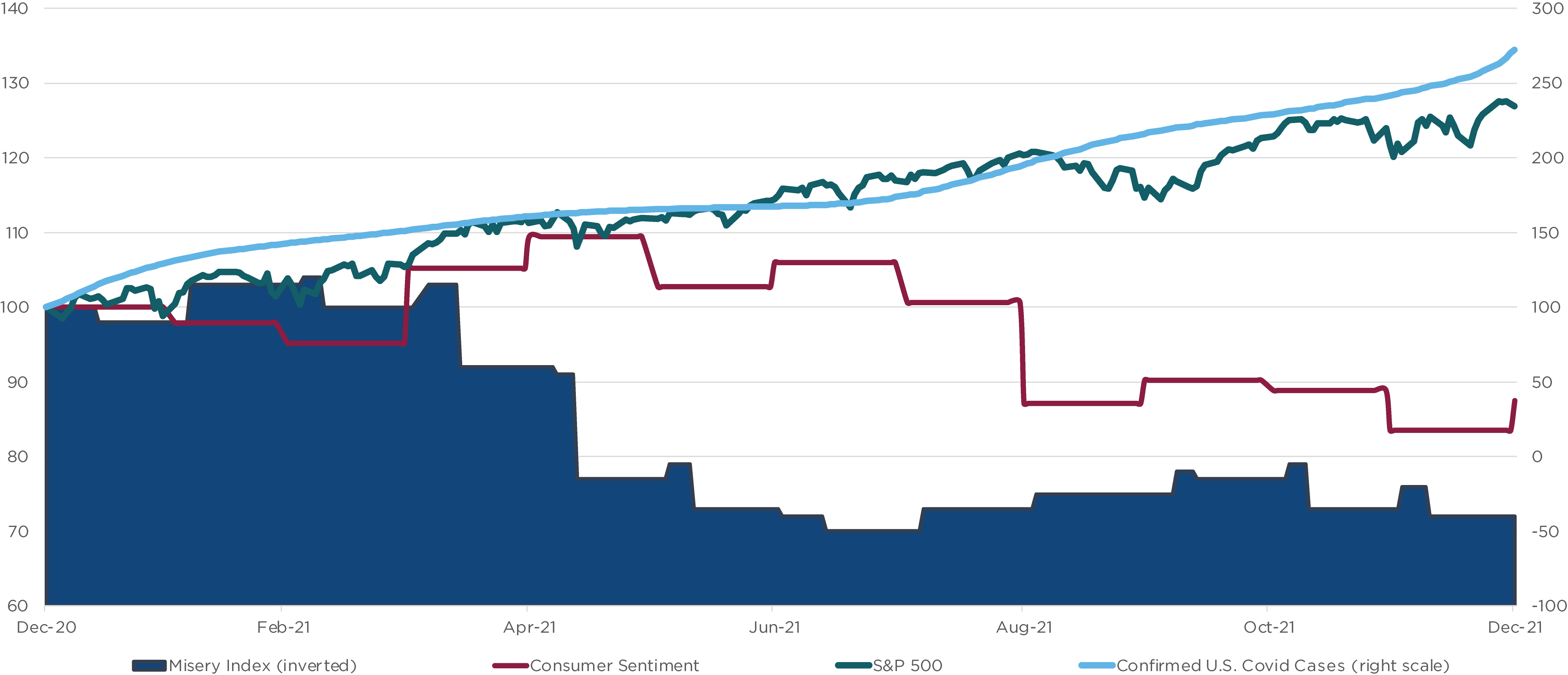

Figure One illustrates this split between financial success (with the S&P 500 Index up 29 percent) and our daily lives, as illustrated by declines in consumer sentiment, the rise in COVID-19 cases, and the increase in the so-called Misery Index.

Figure One: Financial Euphoria vs. Real-Life Challenges (2021)

Sources: Bloomberg, CAPTRUST Research

When you combine 2021 returns for the S&P 500 with similar results in 2020 and 2019, we have just concluded a three-year run in U.S. equities that ranks in the top 10 since 1928. The index showed a price return of more than 90 percent during this period. More impressively, U.S. stocks rose by more than 800 percent (or more than 18 percent annualized) since the Financial Crisis market bottom in 2009. It has truly been an exceptional run.

Given all the turmoil of the past few years, investors should celebrate these results. But they should also remember that returns of this size are abnormal, having been shaped by equally abnormal economic and policy conditions. And while we all hope for and crave a return to normalcy in our daily lives, a return to normal for investors may require adjusting our expectations.

Fourth Quarter Recap

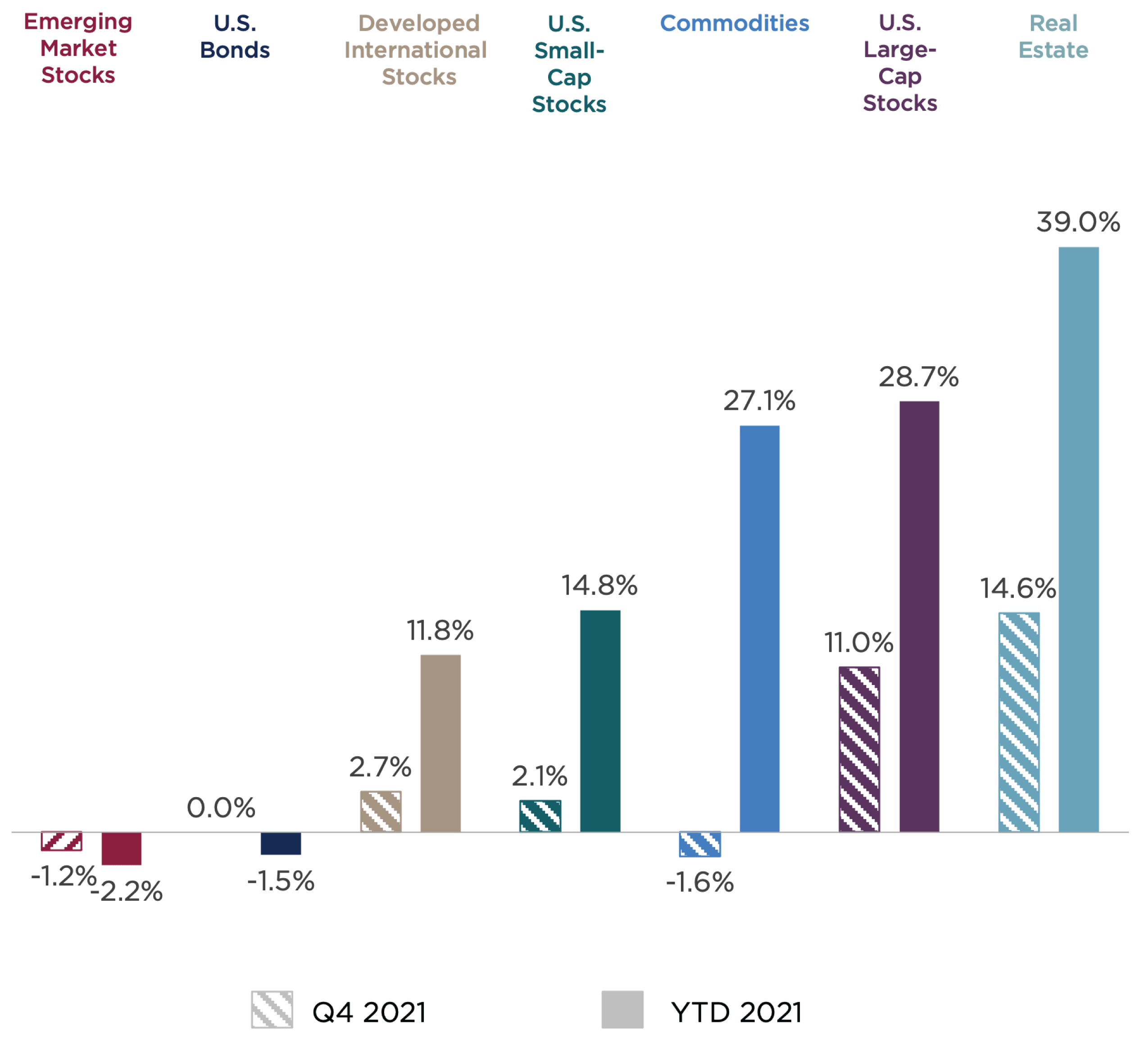

Despite bouts of volatility fueled by virus and policy uncertainty, supply chain woes, and inflation worries, most asset classes posted solid returns in 2021, led by economically sensitive sectors that benefited from reopening trends. Figure Two summarizes asset class returns for the fourth quarter and calendar year 2021.

U.S. large-cap stocks delivered solid returns for the quarter and the year. Notably, the S&P 500 Index failed to show a drawdown of much more than 5 percent during the year and reached new record highs on 70 different days, stats that underscore the steady march higher seen within domestic large-cap stocks during 2021.

Small-cap stocks lagged their large-cap peers but still posted solid, double-digit returns. Along with value stocks, small-cap stocks performed well during the year, as these more cyclical firms benefited from continued progress toward full economic reopening.

International developed market stocks also posted healthy returns for the year, even as China cast a dark cloud over emerging markets. Fueled by a rebound in oil prices, commodities advanced by more than 27 percent for the year despite a fourth-quarter pullback amid rapid spread of the omicron variant. Public real estate added to gains in the fourth quarter despite virus concerns, following steady advances over the course of the year.

Figure Two: Major Asset Class Returns for the Fourth Quarter and 2021

Sources: Bloomberg; CAPTRUST Research. Asset class returns are represented by the following indexes: Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (U.S. bonds), S&P 500 Index (U.S. large-cap stocks), Russell 2000® (U.S. small-cap stocks), MSCI EAFE Index (international developed market stocks), MSCI Emerging Market Index (emerging market stocks), Dow Jones U.S. Real Estate Index (real estate), and Bloomberg Commodity Index (commodities).

Fixed income investors shrugged off rising inflation concerns during the quarter as Treasury yields barely budged, leading the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index to tread water in the fourth quarter. Core bonds suffered a rare (albeit, very modest) loss just over 1.5 percent for the year, representing only the fourth decline for this index in the last 45 years.

Diversification showed benefits within fixed income during the year. Continued strong appetite for risk led to positive returns within credit sectors. Outside the U.S., international bonds faced steeper losses as the dollar strengthened, with the Bloomberg Global Aggregate Bond Index showing a loss of 7.1 percent.

Returning to Normal

In contrast to the steady rise in stock prices witnessed over much of last year, 2022 has gotten off to a rockier start with broad weakness across global equity indexes. Investors are processing several significant challenges and risks facing markets in the year ahead as some of the powerful tailwinds that have propelled markets over the past two years begin to reverse.

The first major change that markets must navigate is the slowing, stopping, and then reversing of the flow of extraordinary stimulus supplied by governments to stave off recession and permanent economic damage over the past two years. Given the rapid snapback in asset prices and economic activity, these policies seem to have been successful, even as they stoked inflation pressures and the potential for market excesses that investors must now grapple with.

Stimulus Fading

On the fiscal side, direct financial support to households will slow dramatically in 2022. Many households face the prospect of no direct government support for the first time since 2019. These programs provided a lifeline to those facing unemployment and financial hardship during the crisis. They also fueled the boom in consumer demand that exacerbated global supply chains already stressed by pandemic-related production interruptions.

The end of government transfer payments represents the first of several important handoffs that must occur smoothly in 2022. Government stimulus has meaningfully and artificially boosted disposable personal income over the last two years. But with stimulus checks in the rearview mirror and child tax credits, student loan forbearance, enhanced unemployment, and eviction moratoriums ending, consumers will need to make up the shortfall through higher wages. This will likely represent a headwind to consumer spending in the year ahead.

Inflation Forces Fed’s Hand

The second major policy shift is the abrupt reversal of course by the Federal Reserve and other global central banks as inflation pressures originally viewed as the temporary effects of economic reopening have advanced into uncomfortable territory for policymakers and consumers.

During the pandemic, we saw a spike in demand for products that were in short supply—everything from work-from-home equipment and exercise gear to cars and trucks—as chip shortages constrained production. In November, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) posted a shocking 6.8 percent year-over-year increase, representing its highest uptick since 1982.

The Misery Index referenced above combines the level of inflation with the unemployment rate, and even while significant progress was made on employment, high levels of inflation worsened the misery of many consumers.

So far, much of this inflation has stemmed from a subset of categories tightly linked to the reopening, such as fuel and energy, along with categories most affected by supply-chain problems, such as autos. As shown in Figure Three, categories representing less than 15 percent of the CPI drove the majority of the increase.

Figure Three: November CPI by Category

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Bloomberg, CAPTRUST Research

Although the blockbuster November CPI reading was largely isolated within a few categories, it prompted a swift and significant reaction by the Federal Reserve. In mid-December, just days after the November inflation results were released, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell surprised markets with an abrupt pivot toward a more inflation-fighting stance, starting with the accelerated wind-down of monthly bond purchases that paves the way for interest rate hikes by early 2022.

Despite this timing, the Fed’s policy pivot was likely fueled by changes in other economic data less widely cited within the financial media, such as increases in employment cost indexes that could translate into broader and more extended inflation risks, as well as continued improvement in jobs data indicating that the labor market was rapidly healing. The risk is that employers facing higher labor costs must raise prices across a wide range of goods and services, creating a self-reinforcing inflation spiral.

Policy Error Risk

This backdrop raises what may be the most significant risk to markets in 2022: a policy error on the part of the Fed and other global central banks. This risk always exists during periods of economic transition, as the growth baton is passed from the public sector during times of economic stress back into the hands of the private sector. But the risk now is exacerbated by the unique nature of the pandemic and the unpredictable path of the virus—factors that fall well outside the margins of the Fed’s typical business-cycle playbook.

If the Fed waits (or has waited) too long to begin tightening, the risks rise that inflation pressures have passed the point where typical containment measures will be effective. If they act too soon or aggressively, policymakers risk stalling a fragile economic recovery amid lingering pandemic uncertainty.

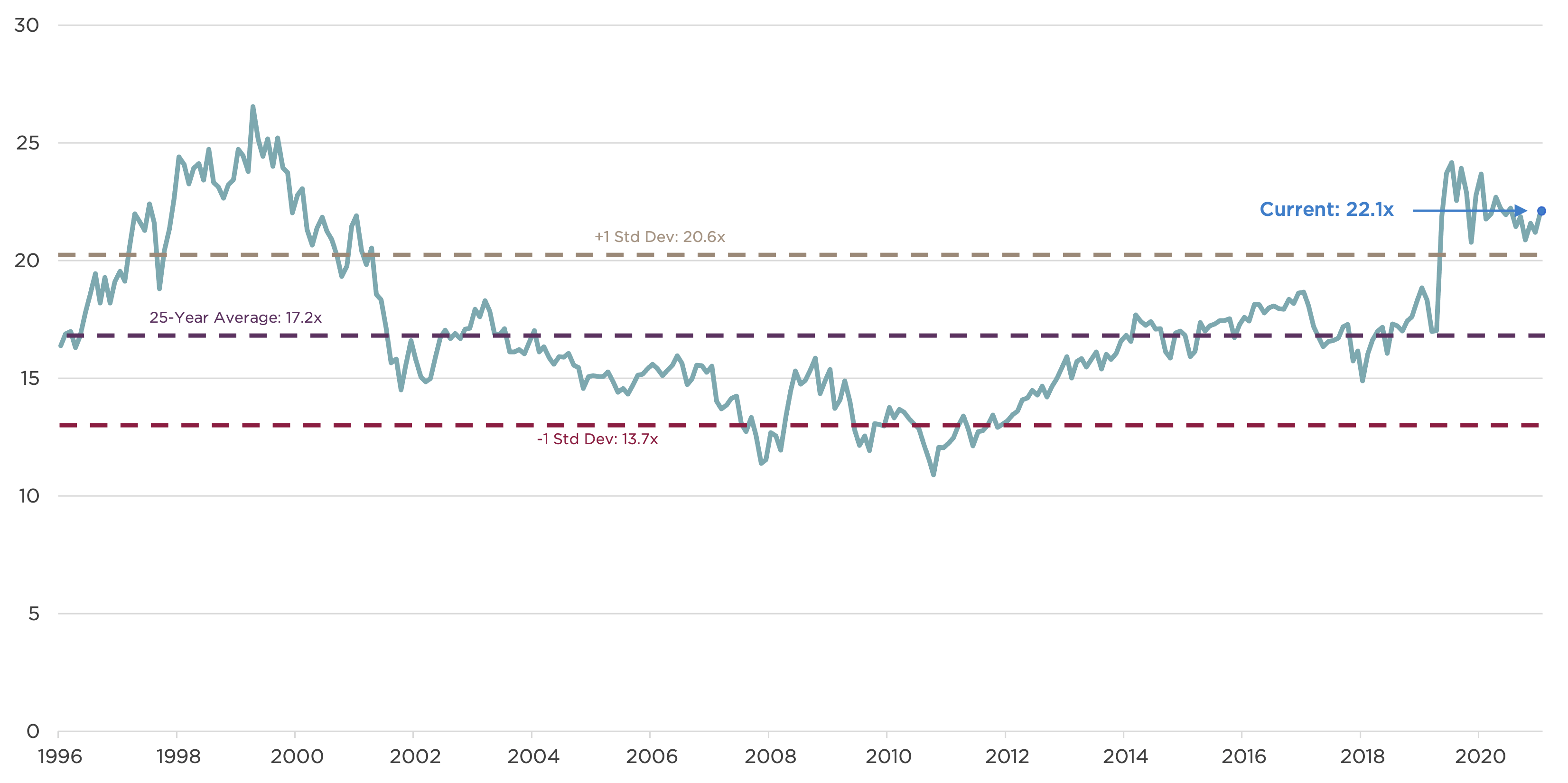

Stretched Valuations

Finally, the level of prices across major asset classes are elevated today compared to historic levels. Prices for U.S. stocks relative to earnings far exceed pre-pandemic levels, while low levels of Treasury yields and historically narrow credit spreads imply lower future returns for core bonds if interest rates rise or if economic conditions soften. As shown in Figure Four, at the end of 2021, the forward price-to-earnings (P/E) multiple for the S&P 500 Index stood just above 22, well in excess of its 25-year average of 17.

Figure Four: S&P 500 Index Forward P/E Ratio

Sources: Bloomberg, Robert Shiller, NASDAQ, CAPTRUST Research.

It’s important to note that P/E multiples have declined steadily over the past year even as stock prices moved higher, as growth in company earnings far outpaced price gains. Looking ahead, we believe that stock prices will continue to be driven by operating results more than multiple expansion. With rates at historic lows and a tightening policy environment, there is less reason to expect significant gains in price-to-earnings multiples.

Not surprisingly, the types of stocks facing the most pressure in the rocky early weeks of 2022 are in the most speculative corners of the market, such as young and unprofitable technology firms that soared in 2020 and the first half of 2021. High-growth, smaller-company stocks tend to be highly interest rate sensitive, because they are valued today on the growth expected to occur far into the future, and rising rates translate into higher opportunity costs while that uncertain growth materializes.

Outlook: Strong, but Slowing Growth

Amid the risks and headwinds described above, we believe that the outlook for both the economy and long-term investors is bright. The U.S. continues to lead a global economy that remains strong. Even if growth fades from the current elevated levels, there remains optimism for positive, although more muted, returns likely with bouts of volatility.

In the decade prior to the 2020 pandemic, the growth of real gross domestic product (GDP) within the U.S. remained rangebound between 1.6 and 3.1 percent. Estimates for 2021 real GDP growth are significantly higher, between 5 and 6 percent, even after accounting for the effects of inflation. Even as rates of GDP growth return to Earth, the U.S. economy is likely to continue to enjoy above-trend growth in 2022. One important driver of continued growth is the strength of household balance sheets. Consumers have amassed trillions of dollars in excess savings over the past two years that will continue to support consumer spending.

We also expect corporate profit growth to slow and return to more normal levels as businesses face higher costs of doing business. The ability of companies to navigate labor shortages and price pressures will be company- and industry-specific, opening the door for material differences in performance within markets based on differences in cost structure and degree of pricing power.

As always, there is a host of unknowns. Although the highly transmissible, yet milder, omicron variant may pave the way for the shift to more normalcy, the path of COVID-19 has proven to be anything but predictable. Meanwhile, a combination of more aggressive government regulation and intervention, a slowing economy, and a real estate crisis have elevated risks within China, adding to geopolitical risks of Russian aggression in Ukraine and policy uncertainty from U.S. midterm elections.

Back to Normal

Our best educated guess for 2022 is that the year will bring a return to normalcy for both our financial lives and our real, everyday lives. We hope that pandemic-related disruptions will be significantly reduced, which should lead schools, businesses, entertainment, travel, and the host of other aspects of our lives to return to normal—or at least not as disrupted as the last two years have seen.

Likewise, it wouldn’t surprise us to see capital markets and financial assets return to more normal behavior. Stocks will likely see more muted returns with increased bouts of volatility. Bonds and other assets like real estate should also see calmer waters. We would be happy with this outcome for 2022: trading the sky-high returns of stocks over the last three years for a return to a more normal—and healthier—regular life.

Editor’s note: While sports metaphors may be clichés, as in this case, they often provide a laboratory for helpful life lessons. Whether you are a fan or not, I hope you will indulge this golf story as a vehicle for a few important investment (and life) lessons. I hope you’ll read on regardless.

Heading into the final hole, Jean van de Velde held a seemingly insurmountable lead. All he had to do was score better than a triple-bogey seven, and he would be the champion of the 128th Open Championship. The victory would be the first major tournament win by a Frenchman in more than 90 years.

Despite holding a three-stroke lead on the final hole of a major tournament, van de Velde pulled out his driver. Fortunately, his tee shot ended on the 17th hole. He was fortunate because the shot was so far right that it carried the water bordering the 18th fairway. Following the errant tee shot, van de Velde could still play it safe and cruise to victory. However, he chose the more aggressive strategy, attempting to reach the green with his second shot. After ricocheting off a grandstand and bouncing off a rock in the Barry Burn, the second shot settled in an area of deep rough.

Van de Velde’s challenges continued as his third shot landed in the water, followed by his fifth shot finding the deep greenside bunker. When the ball finally found the hole on his seventh shot, he had lost his insurmountable lead and, ultimately, lost the Open Championship in a playoff.

The events that led to van de Velde’s collapse at the 1999 Open Championship are similar to the challenges investors frequently face, and the outcomes can, unfortunately, be the same. Many investors learn their major investment lessons the hard way.

Here are a few thoughts to expedite your learnings—or remind you of a few timeless lessons.

Know the Score

Many have questioned whether van de Velde actually knew he was three strokes ahead. Over the past 30 years, we have seen numerous examples of investors with seemingly large leads pull out their driver when all that is required to win is to keep the ball in the middle of the fairway. Typically, these investors have not paused to check their score and continue their strategies focused on building a lead.

Investing is a competition, but an investor’s only opponent is the important financial goals he or she sets for the future. Unfortunately, there are no easy-to-observe scoreboards along the course, so investors rarely check their scores—or, potentially more harmful, they check the market’s scorecard to determine if they are winning.

In the absence of knowing the score, the required decision must be to try for more.

It’s about Time

Another important investing lesson surrounds time. Time is a uniquely critical variable in nearly every decision. Time can be a risk and a risk-reducer. Too much time is a potential risk, and too little time is a potential risk. Consequently, it is imperative to understand how time impacts a decision’s risk profile.

The stock market has been incredible at healing itself. While individual companies have come and gone, with sufficient time, the market has always recovered. Historically, the simple formula for investment success has been: Protect the downside, and the upside has taken care of itself.

While the formula is simple, it’s not easy. Protecting the downside does not mean attempting to avoid the downside; that’s likely a formula for failure. Van de Velde would not have been in a position for victory if he had not taken calculated risks of loss along the way. Rather, protecting the downside is about never being forced to turn a potentially temporary decline into a permanent loss, which most often happens when time runs out.

Van de Velde’s mistake was not triple bogeying a hole. Rather, it was triple bogeying the final hole when he had the most to lose and, more importantly, the least amount of time to recover. Saving for retirement requires emotional discipline, financial sacrifices, and adequate time to capture the full power of compounding.

An early mistake in the investing journey can be overcome; a late mistake, when the stakes are highest and time is shortest, can be catastrophic.

Probability, Not Magnitude

Napoleon Bonaparte said, “The greatest danger occurs at the moment of victory.” Unfortunately, many investors can’t even define what financial victory looks like, and for those that can, it’s terribly difficult to declare it. The thrill of winning is often more fun than acknowledging “I’ve won,” so they overconfidently continue to play the same game, focused on what can go right, and they never stop to question what can go wrong.

The decision to hit his driver on the final hole will forever be questioned. Not because of van de Velde’s abilities—his aggressiveness and execution on the 18th hole was one of the primary contributors to his large lead, having birdied the hole two out of three previous rounds—but because the risk far outweighed the reward. The reward for being right was to win by three (or more) strokes. The risk of being wrong was to not win at all.

Following the death of his dear friend Joseph Heller, The New Yorker published this classic poem written by Kurt Vonnegut:

Joe Heller

True story, Word of Honor:

Joseph Heller, an important and funny writer

now dead,

and I were at a party given by a billionaire

on Shelter Island.

I said “Joe, how does it make you feel

to know that our host only yesterday

may have made more money

than your novel ‘Catch-22’

has earned in its entire history?”

And Joe said, “I’ve got something he can never have.”

And I said, “What on earth could that be, Joe?”

And Joe said, “The knowledge that I’ve got enough.”

Not bad! Rest in peace!

It is critical for investors to clearly define what success looks like to them, and if they are fortunate to be able to declare victory, stop the game and be thankful for having enough.

Comprehensive Financial Planning

An individual’s investment strategy is just one element of your comprehensive financial plan. The planning process helps you clearly define what victory means. It identifies the future financial goals that you are competing against and establishes a strategic spending-saving-investment game plan focused on maximizing the probability of success—not the magnitude of success! Finally, it provides the necessary context you need to accurately check your current financial scorecard and allows you to know how much longer you need to compete.

Heying (pronounced Hi-ing), 50, who has a Bachelor of Science degree in social work as well as a Master of Pastoral Ministry degree, grew up in Ossian, Iowa. The youngest of seven siblings, she learned the value of caring for the less fortunate from her devout Catholic parents.

“My oldest brother has Down’s syndrome,” Heying says. She remembers her parents were told to put their disabled son in an institution and move on with their lives. “But that was not the choice they made,” she says. Instead, Heying grew up with a fierce understanding of making room for everyone.

After graduating from college, she worked for more than a decade as a social worker and pastoral minister for St. Stephen’s Human Services, an independent nonprofit organization fighting poverty and homelessness. There, she learned firsthand how important car repair is for people who are underserved.

“I heard it repeatedly,” says Heying. Clients told her, “I can’t afford to get my car fixed, and I’m going to lose my job.” Without the ability to pay rent, they could easily find themselves living on the streets.

Oftentimes, she helped someone push a broken-down vehicle around the block so it wouldn’t get towed.

Clients would live in their cars when they couldn’t get a bed at the homeless shelter, Heying says. One client stayed in his automobile so frequently that when he applied for a job, he would give his address as 1994 Nissan Maxima Avenue.

“The details of the stories were different, but everything depended on a car repair,” she says. She was plagued with a recurring thought: Somebody should do something about it.

The Pros and Cons

Heying began agonizing over returning to school to become an auto mechanic. She loved her social services career and was still paying graduate school loans. “I wrote a pro and con list, and there was nothing in the pro column,” she says.

“You know it’s a calling—or something bigger—when you make a list and there is nothing in that pro column, but you can’t stop thinking about it,” Heying says. “There was no logical reason to do it, but I kept seeing the need and thought, ‘Somebody needs to make this happen.’”

So, at age 38, Heying enrolled in a two-year associate degree program in auto technology at Dunwoody College of Technology. “I went into the whole thing reluctantly,” Heying says. She walked into the first day of class thinking, “Why am I taking out more student loans to get a degree I don’t particularly want to get, that I don’t know if I’ll be good at, to meet a need I don’t know how to meet?”

Shutting Out Self-Doubt

Heying had changed the oil in her motorcycle a few times but knew little else about auto repair. “I’m good at organizing people and talking about feelings,” Heying says. “Those are more my wheelhouse than fuel injection.”

She remembers her first day of class at Dunwoody. Automotive instructor Dave DuVal told the students to face the wall where the crankshafts were hanging. Heying didn’t know which way to turn, so she followed the lead of the young men in the class. “I was very much a novice,” Heying says. “It was a huge and humbling learning experience.”

Heying doubted her decision for months, she says. “The whole thing was awful. I loved Dunwoody, let me be clear, but in a program that is designed largely for 18-year-old boys, there is a different energy and style that involves a lot of yelling and drill-sergeant-like talking.”

She often thought she didn’t fit in and considered giving up. “Halfway through the first semester, I could not flare brake lines for the life of me,” Heying says. “I couldn’t do it, and, one day, I burst into tears.”

Embarrassed and humiliated, she was ready to quit, but DuVal talked with her. Heying told him about the need in the community for reasonably priced auto repairs. That day, DuVal told Heying she had a great vision and committed to helping her every step of the way.