Today’s graduates also face a very different environment from their older siblings, cousins, parents, and grandparents. Instead of the anxious yet still carefree final months on campus, many students endured a more solitary experience from their dorm rooms or apartments—or their parents’ basements. They will also enter a job market that is far from normal. The pandemic has altered the landscape for how and where work is done, and it’s unclear how many of these changes will persist once the crisis has passed.

Even so, there will be no shortage of financial wisdom showered upon new grads from commencement speakers, proud parents, well-wishing relatives, and friends on social media. The advice they receive will likely include financial rules of thumb that have, in many cases, been passed down through generations, like a battered, leather- bound portfolio or briefcase.

Rules of thumb are simple frameworks to help us make complex decisions based on limited information and imperfect knowledge of the future. Some, like the widely used rule of 72, are rooted in math, while others are

driven by behaviors. Either way, their value is that they don’t have to provide perfect predictions to be useful. Instead, they serve to nudge us toward more successful behaviors and provide simple frameworks to consider the long-term consequences of everyday decisions.

Even if the current environment is very different from the past, there is always value in learning from people who have survived and thrived amid any number of challenges, shocks, and prior tectonic shifts in how we live and work. Many of the financial tips offered to graduates 50 years ago remain just as true today—while others have likely changed.

Budget

What hasn’t changed. The most fundamental driver of lifelong financial success is the ability to set and keep to a budget. You can only save or invest what you don’t spend, and this simple truth forms the basis for perhaps the most famous financial axiom of all time: Pay yourself first.

This phrase, coined in a 1926 book on personal finance, titled The Richest Man in Babylon, has certainly stood the test of time and has been expanded over the years with additional parameters. The 80/20 rule, for example, suggests spending 80 percent of take-home pay on needs and wants, with the remaining 20 percent aimed toward savings or debt reduction. This provides a useful, simple framework for the budget-savvy.

But after the initial shock subsides—Wait, you want me to reduce my paycheck by 20 percent? —the natural next question is what to do with that money. There is no shortage of competing and worthwhile priorities, including paying down college debt, saving for retirement, or building toward a down payment on a home. But the experienced advice-giver will have a ready answer: The rainy day fund. Conventional wisdom calls for three to six months of living expenses kept safe in a savings or money market account that may be just a little inconvenient to access, thereby reducing the temptation to raid the piggy bank.

This is sound advice indeed, and what’s great about the second tip is that it requires knowledge of the first. After all, you can’t plan for six months of living expenses until you know what those expenses are.

What may have changed. Fortunately, today there are many tools, apps, and services to simplify and automate the process of creating a budget. Instead of legal pads or spreadsheets, a smartphone app will scan accounts to track and categorize spending. Other apps will round purchase amounts up, turning spare change into gradual progress toward the rainy day fund. But as for the size of that fund, today’s environment may call for a more customized approach to the standard six-month target.

Even before the pandemic, there was already a shift underway toward more flexible, independent work arrangements—the so-called gig economy. And all else being equal, gig workers probably need an even larger emergency fund for two reasons: to smooth out the more variable nature of their income and to protect against events (illness or even a flat tire) that prevent work. And as many experienced during the pandemic, unemployment benefits for gig workers are also less clear.

Workers in more traditional jobs may also need to adjust the six-month target to the current environment. A contemporary and clever twist on the six-month rule is to take the current unemployment rate (in percentage points) and keep that number of months’ expenses in reserve, at a minimum. But with a recent unemployment rate of 6.1 percent, this takes us right back to where we started: a six-month target. Things may not be so different, after all.

Debt and Credit

What hasn’t changed. As with budgeting, the most basic advice with respect to debt management is both simple and timeless: Live within your means. Whether drawn from a philosophical basis—such as the belief that money doesn’t buy happiness—or from the practical recognition that debt reduces flexibility and limits future choices,

debt management is a key to financial wellness.

In addition to the stress that accompanies a high level of debt, debt carries tangible costs. Establishing a solid credit history and high credit scores can lead to far more attractive loan terms.

Credit decisions can also influence career paths, both directly and indirectly. Increasingly, employers include credit checks as part of their preemployment background checks. Just as importantly, keeping debt levels under control can mean the difference between being forced to remain in an adequately paid but miserable job or one with limited potential for future growth versus having the flexibility to pursue opportunities that sometimes require a nonlinear path toward a more rewarding career.

What may have changed. For today’s graduates, there are two important factors that are different from those of prior generations: the prevalence of student loans and the historically low interest rate environment. Over the past decade, the amount of student loan debt outstanding has reached more than $1.7 trillion—an amount far above both credit card and auto loan balances.[1]

Another difference is the current interest rate environment. Over the past three decades, the overall level of interest rates (as measured by the benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury yield) has steadily declined. As shown in Figure One, rates for consumer borrowers have generally followed suit, aside from credit cards, which have retained their steep premiums.

In the short term, low rates represent a boon to those early in their careers, as they reduce the monthly maintenance cost of debt. And unlike savers later in their careers, the opportunity cost of low interest rates on savings or money market balances is typically low. The risk is that low debt service costs lead to overextension, particularly if borrowers make decisions on how much of their car, house, or even graduate school degree they can afford based solely on the current, historically low monthly payment. Although we don’t know what interest rates will look like a decade from now, they’re unlikely to be significantly lower.

Homeownership

What hasn’t changed. When we think of debt, the natural next topic is homeownership and the classic bit of financial advice that forms the very cornerstone of the American dream: Save 20 percent toward a down payment and buy your first house as soon as you can.

The fundamental financial case for homeownership has not changed. Owners build equity in an asset that they can use, enjoy, and improve with sweat equity, in addition to the potential tax benefits. This is in addition to the less-tangible, nonfinancial benefits such as a greater ability to personalize a home to the owner’s needs, the

notion of putting down roots, establishing a stable home base for raising a family, and enjoying a greater sense of community.

What may have changed. Even with mortgage rates at historically low levels, soaring home prices have pushed home affordability out of reach for many potential buyers.

One contributor to this delay may be that people are forming households later in life than previous generations. Dual incomes can be important for many first-time buyers.

Holding aside these financial aspects, the current reality is that homeownership may not be right for everyone. Today’s workers are far more mobile than they were in prior generations. A 2019 Department of Labor study reported that workers held 5.7 jobs on average from ages 18 to 24 and an additional 4.5 jobs from 25 to 34.

However, it is important to note that this study only included individuals born between 1957 and 1964 and therefore may underrepresent the degree of mobility in today’s younger workforce. And the 2020 pandemic may have only accelerated this trend. Another recent survey conducted by Harris Poll exclusively for Fast Company showed that the majority (52 percent) of U.S. workers are considering a job change in 2021, and as many as 44 percent have plans to do so.

Considering the up-front costs of buying a home, another common rule of thumb is that buyers should plan to remain in their homes for at least five to seven years just to break even. Unless the home’s location could support four to six job changes, on average, during that period, renting could be more attractive than buying.

Even so, delayed homeownership doesn’t eliminate the need to save for the eventuality of buying a home, and the key is to begin to accumulate equity elsewhere. Home prices (and, therefore, down payments) are likely to increase over time, and without accumulating liquid savings that can grow at a similar rate, a purchase five or ten years hence becomes that much more difficult.

Investing For Retirement

What hasn’t changed. Saving and investing for retirement have long been fertile grounds for financial wisdom. And for good reason. For those in their early 20s, retirement is maybe 40 or 50 years away. With such a long period before the payoff is realized, it’s even more difficult to make sacrifices today.

The gold standard retirement savings rule of thumb is to save 15 percent of pre-tax income, including any employer contributions. For those who are able, this sets an excellent trajectory that can dramatically increase the likelihood of retirement success. But with the competing priorities already discussed—student loans, credit card payments, and building a rainy day fund—it can be difficult for many new graduates to hit this target right out of the gate. But all is not lost. Experienced advice-givers have a few more go-to tidbits to pass along:

Maximize the match. Even if you can’t hit the 15 percent target, do everything you can to maximize your employer’s contributions, even if this means slowing down your progress toward other savings or debt reduction goals.

Set yourself on autopilot. Many 401(k) and 403(b) plans offer automatic escalation features that increase paycheck deferrals by, for example, 1 percent each year—a level hardly noticeable for most people.

Check progress regularly. Even if your goal is still several decades away, set milestones and checkpoints to measure and celebrate success. This can take the form of retirement planning sessions with a qualified retirement plan advisor. If this kind of service isn’t available, even simple measuring guidelines can make progress feel much more tangible and attainable. Figure Three shows one such benchmark based on target retirement balances by age.

Look, but don’t touch. Given the job-switching behaviors already discussed, younger workers will face the temptation to take a distribution instead of a rollover when leaving a job. Such premature distributions are a common mistake that should be avoided whenever possible. What seems like a small sum of money can have massive implications on long-term success, particularly after early withdrawal penalties.

What may have changed. Given workforce trends already discussed, one piece of advice many of us may have once received is becoming less and less applicable: Find a good company, build your career there, and retire with a comfortable pension. Today, it’s estimated that only 15 percent of private-sector workers have access to a traditional pension plan, according to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Another common, but outdated, rule of thumb for retirement investing is the rule of 100—investors should subtract their age from 100 to set the percentage of their portfolio to hold in stocks. Over the past two decades, the industry has invested massive resources in studying the best approach to asset allocation over a retirement saver’s career. The rule of 100 may leave retirement savers underexposed to equities both at the beginning of their career and toward the end, when their accumulated balance must support several decades of spending.

A more modern approach is, once again, to take advantage of automation. Many retirement plans today offer age- based target date funds or other solutions that offer diversified portfolios with set-it-and-forget-it convenience. In addition to eliminating the need for manual adjustments, these solutions may also reduce investors’ temptations to make changes in response to short-term bouts of volatility.

Finally, most retirement plans today offer a Roth option—the ability to save after-tax dollars today and receive qualified distributions tax-free in retirement. Although everyone’s tax situation (and view around future taxes) is different, a simple rule of thumb is that if your current tax rate is lower than you expect in retirement, you should direct at least some retirement savings toward Roth. If nothing else, the ability to choose between taxable and nontaxable buckets can be a powerful planning tool.

Those in the position to offer financial advice to those just setting out can make a huge impact—assuming, of course, that the advice is heard, understood, and relevant to the current environment.

Ambitious young readers of Fortune magazine’s 1956 article, “Twenty Minutes to a Career … Or Not,” were advised to consider the standard 20-minute job interview as an event that would settle their careers for life and that they should consider a job offer in terms of a lifetime career. Simply considering the number of bankruptcies, corporate mergers, and acquisitions since then, it is unlikely that many of the class of ’56 retired from their first jobs.

The best advice is always good advice that is followed. And often, it’s the stories of our own struggles and mistakes that have the greatest impact. No matter our level of success, there are always things that we would have done a little differently—and these are likely the most impactful lessons to pass along to the next generation.

[1] 2024 Student Loan Debt Statistics: Average Student Loan Debt – Forbes Advisor

The point of the exercise: making sure each spouse would know what to do if the other were not there—especially if one of them died.

“I think a lot of people are afraid to think about those situations,” says Brennan, a former hedge fund manager who quit her job to start the financial education website smartmoneymamas.com.

But thinking about a spouse’s death is something every married couple should do because not thinking about it can leave you unprepared for one of life’s most difficult transitions. When a spouse dies, money is not the only thing on your mind, but it can be more or less of a burden depending on what you do before and after the loss.

Couples who discuss and plan for every possible scenario, including dying together or separately, soon, or far in the future, after a long illness or quite suddenly, are less likely to be blindsided by the financial fallout, says Mike Gray, a CAPTRUST wealth management advisor working in Raleigh, North Carolina.

“When you do this kind of planning, you have to put on the dark glasses, not the rose-colored glasses,” he says. “The bad stuff, even though it’s remote, might happen.”

And when it does happen, knowing exactly what to do about money, at least, can make a horrible situation just a bit more manageable.

Before a Spouse Dies

Most people know the basics of estate planning: You draft and sign wills and set up trusts, perhaps along with letters of intent to make sure your wishes are fully understood. You also assign powers of attorney to those who would handle financial and healthcare decisions if you became incapacitated. Likewise, when you sign up for life insurance or open a new 401(k) account, you name beneficiaries for those funds in the event of your death.

But if the documents detailing your last wishes are sitting in physical or digital files somewhere, gathering real or virtual dust, that is a problem in and of itself.

For example, a spouse you expected to act as executor of your estate may no longer be suited for that role years later if he or she develops cognitive impairment. An adult child who you thought was too immature when you first drew up the documents might be a better choice.

Divorces, new marriages, deaths, births, and estrangements can also change your intentions. That’s why it’s so important to review your estate planning documents at least every few years, Gray says.

That includes often overlooked details, such as naming beneficiaries on pensions, insurance, and investment accounts. Many people don’t realize that named beneficiaries will almost always get the designated funds, even if the deceased expressed different wishes in a will.

“There are horror stories out there about former spouses who are named beneficiaries and who get money intended for a new spouse or children,” Gray says.

But updating your directive documents is not enough. It’s also important to talk with your spouse often about what is going on in your financial life and what should happen if you die or become incapacitated.

Some people go as far as insisting their family and, sometimes, business associates run a dress rehearsal of sorts, says Mark Chamberlain, a CAPTRUST wealth management advisor in Chesterton, Indiana.

Chamberlain says he heard of one executive who called his family and associates together one day and announced: “My plane just disappeared, and I’m dead. What’s next?”

In about three hours, Chamberlain says, the group put together a draft document that would guide their actions if the death had actually happened.

Couples who try the same thing might learn that the wife does not know the passwords for her husband’s bank and credit card accounts or that the husband does not know how his wife pays the water and phone bills online, Chamberlain says.

Experts recommend putting such vital information, including contact information for key people such as employers, attorneys, and financial advisors, in a single, safe place.

Smartmoneymamas.com founder Chelsea Brennan recommends compiling a family emergency binder containing everything from bank and email passwords to military records and memorial service wishes.

One more consideration: When a crisis hits, neither of you may be around nor fully capable, so besides making sure each other knows where all this stuff is, make sure someone else does too, Gray says.

After a Spouse Dies

In the days and weeks after a spouse’s death, financial and other logistical tasks can seem overwhelming.

“When it happens, take a deep breath and realize you need to grieve and most of this stuff doesn’t have to happen the day after or the week after you lose your spouse,” Gray says.

“I think you need to understand that you are going to feel literally like someone has put you on a raft and dumped you in the middle of the Pacific Ocean,” says Marie, a 61-year-old attorney who lost her husband a few years ago. “I felt completely set adrift in a sea of uncertainly and confusion.”

But Marie, who had been married for 11 years, says the fact that she and her husband had shared complete transparency and complete trust about their finances gave her confidence as she went through the settlement of his estate. “As insecure as I was, had I not known that I was financially secure, it would have been even worse,” she says.

Not everyone is as fortunate. Jan Warner, 70, a retired mental health professional who started a Facebook group for grieving spouses after her own husband died in 2009, says that surviving spouses sometimes find unpleasant financial surprises: “There are people out there who think their net worth is in the millions, and they find out they are bankrupt.”

Warner, of New York City, says she was blindsided by her own late husband’s decision to leave about $1 million she was expecting to other family members. While the decision did not leave her destitute, it added pain to an already painful time, she says.

Warner, who wrote a book called Grief Day by Day, says her advice for new widows and widowers is to set some goals but cut themselves some slack.

“I gave myself a chore for the day. One of them was paying my bills. I really didn’t have the capacity to do much of anything.” Warner says she found inspiration from a wall plaque that said, “Have an Adequate Day.”

Many bereaved spouses find that activities such as meetings with probate attorneys actually make them feel better, Gray says. Such professionals “have been through this dozens of times,” Gray says. “They know what to do and where to go. The conversation can give the bereaved a lot of comfort. There are people there to help you.”

Funeral directors also offer more help than many people realize. For example, they often notify Social Security of the death and order death certificates. Other essential early tasks include notifying employers and insurers and making sure bills get paid. But some tasks, such as updating names on deeds and titles, can wait a bit.

Once you have more immediate tasks handled, it’s important to meet with both a tax professional and your financial planner to assess your new situation and make plans for your future, Gray says. Meeting with a planner to go through assets, income, and a forward-looking investment strategy gives many people “a huge chunk of peace of mind,” he says. “It helps them see that they are going to be OK.”

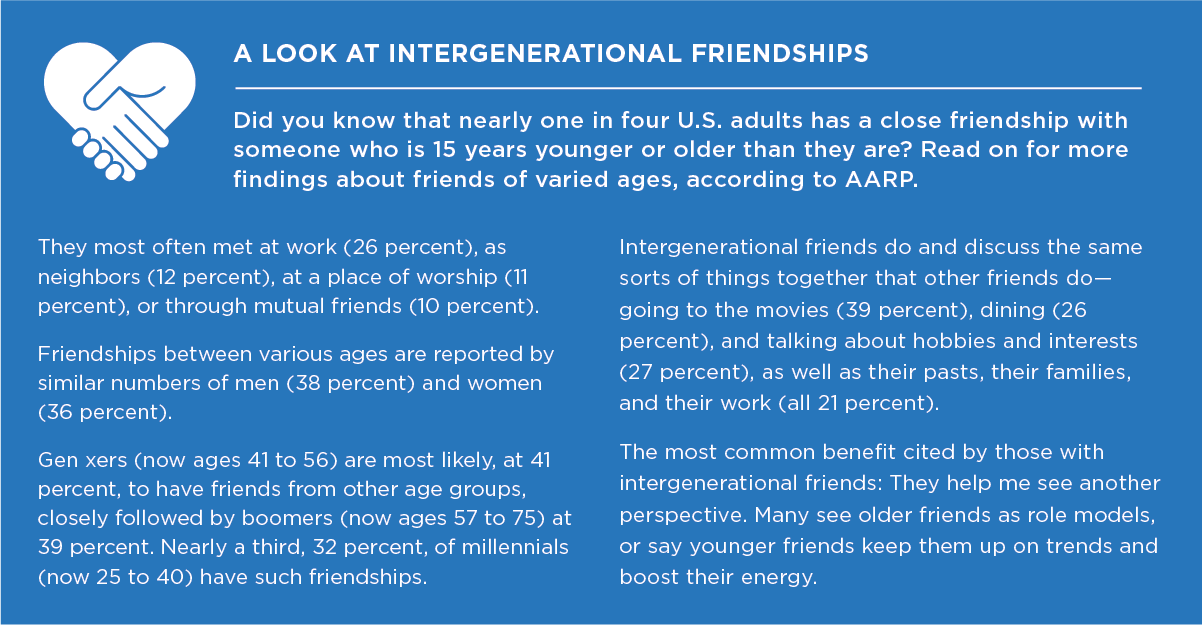

“It turned out he was my upstairs neighbor. Pretty soon, we got together to share food, and I met his wife and their best friends,” says Varalli. Before long, the group was boating, snorkeling, and enjoying other adventures together.

The fact that her neighbor was 83, and that his wife and their friends were in their 60s, wasn’t a problem—it was a bonus, Varalli says.

“I have plenty of really close friendships with folks who are in their 60s, 70s, and 80s,” says Varalli, a high school Spanish teacher living in Honolulu while on sabbatical from her job in San Francisco. Friends of varying ages, she says, share perspectives and stories that broaden her horizons and make life more fun.

Varalli and others who seek out intergenerational friendships are on to something, say social scientists, mental health advocates, and others working to break down artificial age divides.

Finding Common Ground

A dozen years ago, the word intergenerational was unknown to most people, says Elly Katz, of Los Angeles. Back then, Katz, now 70, was a graphic designer working in Boston and itching to do something new and meaningful. She had a vague idea that she wanted to combat ageism.

Her epiphany came one day when she was driving her 16-year-old son to school: What if, she thought, she could get teens to share their phenomenal energy with older adults?

The result was a matching program called Sages & Seekers, which Katz started with one private school in Boston and later expanded to Los Angeles. The program now includes college students, as well as high schoolers, paired with adults aged 60 and above. And because the pandemic forced it to go online, participants now come from all over.

The program brings small groups of younger and older people together for brief gab sessions and then allows self-selected pairs to bond in longer sessions over several weeks. There are no mentors or mentees—the idea is to encourage friendship and understanding among equals, Katz says.

Older people often come to the program believing that “kids are disrespectful and not interested in doing anything off their phones,” Katz says. Teens and young adults often expect to have nothing in common with elders, she says, but both groups are regularly proven to be wrong.

That was the case for Nita Bryant-Azmar, 76, of Los Angeles, and Mrudula Akkinespally, 19, a pre-med student at UCLA who lives in San Diego. Bryant-Azmar, a retired nurse and administrator, says that after some negative experiences in the workplace and elsewhere, “I had decided that people under age 30 were not my cup of tea.” Akkinespally says she thought people over age 40 were lazy and boring.

But over the course of their online chats this winter, Akkinespally learned that Bryant-Azmar had celebrated her last birthday with a 76-mile bike ride, liked some of the same TV shows she did, and had once struggled with college chemistry, just as she did. Bryant- Azmar learned that Akkinespally was thoughtfully planning a 25th anniversary party for her parents and was a sympathetic listener when Bryant-Azmar talked about missing her late husband. Bryant-Azmar, who has participated in the program four times now, says she’s learned that “there are some young people out there who are just wonderful.”

Akkinespally says she’s found a new role model in Bryant-Azmar, who skis, hikes, and travels widely. “When she told me how active she was, my mind was totally blown,” the younger woman says. “She has inspired me to take my health more seriously because I want to be as active as Nita is when I’m her age.”

Michelle Cavelier, 18, an American of Colombian descent, who just finished her last two years of high school in Bogota, and Clif de Cordoba, 76, a retired educator from Los Angeles, who has Puerto Rican roots, say they also formed a true connection in their video chats. They chose to speak entirely in Spanish and spent a lot of time discussing struggles with their cultural identities, the two say.

“I never expected in my wildest dreams that I would connect with someone that young about these things I’d been going through these umpteen years,” de Cordoba says.

Cavelier says: “It doesn’t matter the age; you can connect with anyone, as long as you are able to open your heart.”

Expanding Your Friend Zone

Most of us, of course, don’t meet our friends through a formal matching program. When we are young, we meet friends at school and through activities. Later, we make friends at work, in our neighborhoods, and through our various roles: Parents meet parents, retirees meet retirees, worshipers meet other worshipers, and golfers meet other golfers.

Often, those paths lead us to form friendships almost exclusively with people of our own approximate age, says social scientist Kasley Killam, founder of Social Health Labs, San Francisco. “People don’t even think to diversify the ages of their friends.”

Irene Levine, a psychologist and journalist who writes The Friendship Blog (thefriendshipblog.com), agrees: “Unfortunately, there is a natural tendency to seek out friends who look, act, and talk like us. Being open to intergenerational friendships and other differences expands the potential pool.”

Thinking outside the age box comes naturally to some but takes more effort for others.

“There are so many wonderful opportunities if we just think about them,” says Colby Takeda, a senior manager with Blue Zones Project by Sharecare, an organization that promotes healthy communities.

Takeda, based in Honolulu, says any outing in your neighborhood is an opportunity to seek out new faces of various ages—not just the other stroller pushers, power walkers, or whoever looks the most like you. “When you are in the community garden and see the lady in the plot next to you, just say, ‘Hello,’” he suggests.

Likewise, when you are looking for groups to join and activities to pursue, consider whether they might attract people of various ages. And, Takeda says, don’t dismiss a group you think is only for older or younger people.

Varalli had that kind of open mind when, during her first months in Hawaii, she joined a bicycling group called the Red Hot Ladies Cycling Club. Originally formed for women over age 50, it now includes women and men with an age range of 27 to 78, says co-founder Patricia Johnson.

Johnson, who happens to be the oldest member, says she started cycling herself in her early 60s, to connect with young tech workers when she was a personal development consultant in California. “The young people were not using golf as a way to connect,” she says.

She now helps lead weekly rides in which participants, regardless of age, can break into self-selected groups that ride at various speeds and challenge levels. The slower groups “are not necessarily older,” she says—something that helps break age stereotypes and makes the rides more fun and interesting. She and Varalli often ride in the same easy-going group.

“Cycling definitely is a place where age doesn’t make much of a difference,” Johnson says.

Riding with younger people has helped keep her connected with the broader world, Johnson says. For example, during the early months of the pandemic, members who were healthcare workers talked about the stresses of their jobs; other working adults in the group shared their financial worries. Those are perspectives a group composed entirely of retirees would have missed, Johnson says.

Varalli says she is convinced that having friends across the age spectrum just makes life richer.

“When we segregate by age, we tend to start segregating in other ways,” she says, “and putting ourselves in very small boxes.”

He has stretched the limits of the sport of high-wire walking, crossing 1,500 feet above a Grand Canyon gorge on a dangerously swaying cable with no harness or net. He was the first to cross directly above Niagara Falls through swirling wind and mist so heavy that he was at times blinded. And in March 2020, he topped all that by walking through corrosive fumes across the crater of an active volcano in Nicaragua, above a magma lake at more than 2,000 degrees. And he can’t wait to do more.

“Before I got to the other side of the volcano, I was already thinking of 15 other events I could do,” Wallenda, 42, says.

Growing Up Wallenda

Wallenda was just 18 months old when his mother first put him on a tightrope in the backyard. This was normal parenting practice in the family, as his sister, cousin, and other relatives also trained from an extremely young age. His mother, Delilah, even walked the wire while pregnant with him, so you could certainly say he was born into the lifestyle.

A favorite saying of his great-grandfather, the legendary circus performer Karl Wallenda, is Wallenda’s truth: “Life is on the wire, and everything else is just waiting.”

The family traces their acrobatic history back over 200 years to Germany. They moved to the U.S. in the 1930s after John Ringling saw their act in Havana and hired them for his “Greatest Show on Earth,” according to The New York Times. Wallenda holds multiple Guinness World Records, including the steepest tightrope walk, highest blindfolded walk, highest wire crossing on a bicycle, and tallest four-person pyramid on a high wire.

His wife, Erendira, is also from a long circus lineage. “She comes from seven generations in the business on one side, and eight on the other,” Wallenda says. According to the Washington Post, he called her a “ballerina in the air” after she hung by her teeth from a helicopter over Niagara Falls, breaking Wallenda’s iron-jaw world record.

Contrary to what some might think, his family didn’t pressure him to carry on the tradition. “My parents saw the struggles of the entertainment and circus world and did everything they could to push me out of the industry,” Wallenda says. “When you’re in front of a live audience from the age of two—that’s when I started performing, not on the wire but as a clown—there’s that attraction,” he says. “I was passionate about it.”

His three adult children have careers in the military and health care. “They all are really good at walking the wire, but we never let them do it in front of an audience. It was to protect them from that itch, that bug, and let them make their own decisions when they got older,” Wallenda says.

There’s a video of Wallenda walking between two skyscrapers in Chicago for a 2014 TV special. In the wide shots, the silhouette of his body looks like a bird flying through the air, the balance pole extending like wings on either side. The cable slopes up at 19 degrees, the steepest ever recorded by Guinness World Records.

As he ascended, he spoke into a mic. “What an incredibly beautiful city at night Chicago is,” he said, as casually as if he weren’t teetering on a cable the diameter of a penny. “God is in control,” he added. At the top, he took an elevator to the ground, went back to the tower, and put on a blindfold to walk another tightrope. Another Guinness World Record. Small wonder the media has dubbed him the King of the High Wire.

Wallenda, like others in his family, typically eschews a harness or safety net whenever local ordinances and his contracts permit. Life on the wire is normal to the Wallendas, but the family has endured tragedies over the decades. The patriarch, Karl, lost his life in a fall from a tightrope on a beachfront in San Juan, Puerto Rico, in 1978. Wallenda speaks openly about the accidents. “Seven [family members] fell in 1962,” Wallenda says. “In 2017, we fell doing an eight-person pyramid, and there were serious injuries.”

Wallenda and his sister, Lijana, were rehearsing the intricate formation in Sarasota, Florida, when their moving pyramid suddenly collapsed. Wallenda and two performers managed to catch the line, but the others hit the ground. Lijana landed face-first and nearly died, with surgeons requiring more than 70 screws and plates to repair her broken bones. Badly shaken, Wallenda nevertheless found substitute performers, did a modified show, and locked away his trauma to fulfill the contract. He wrote about the emotional aftermath in his book, Facing Fear: Step Out in Faith and Rise Above What’s Holding You Back.

Calculated Risk

The fall affected him mentally, for a bit. Accidents are always going to happen, Wallenda says. “My risks seem more intense because I’m walking on a wire, but it’s a very calculated risk,” he says. “Do I arrogantly say that I’ll never fall? No. It’s risky and dangerous—and it could take my life at some point, but I train as hard as I can so that that doesn’t happen.”

“I absolutely trip. In training, it happens often,” Wallenda says. “Sometimes, on the ground, you trip,” he says. “However, if I trip up there, it could cost me my life. But for me, walking on the wire is the same as walking on the ground.”

In his early 40s, Wallenda says wire walking hasn’t gotten physically more difficult over time. Wallenda family members tend to age with extreme grace, often continuing on the high wire into their 70s or 80s. “It’s our passion,” Wallenda says. “Tell Tiger Woods to stop golfing or Michael Jordan to stop playing basketball—it’s not going to happen.”

He shares the story of his mother having a hip replacement in her 60s. “She had to convince her surgeon to put in an athletic hip instead of a regular one for average people,” Wallenda says. “My mom said, ‘No, I’m an athlete. I need the titanium hip.’” Six months afterward, he and Delilah—and her new hip—walked together on a tightrope 100 feet in the air for a show in Tampa.

As he gets older, Wallenda notices the difference more on the mental side of things. “You think a little more before you do things,” he says. “In my book, Facing Fear, I wrote about the psyche and the internal dialogue that we all deal with as we get older,” Wallenda says.

“Fear can hold us back from success, from who we’re created to be,” Wallenda says, “but it’s a stepping-stone.”

“Failure creates fear … without failure, you can’t get to success,” he says.

Wallenda draws a comparison to an investor’s fear of losses and how that can hold them back from stock market success. He recalls his first meeting with a financial advisor. “My advisor did a risk analysis. It’s to see how risk averse you are and how much risk you want to take in the stock market.” After Wallenda completed the questions, the advisor was astonished, saying, “Wow. Never in my career have I seen someone who wants to take that much risk with their money.”

All In

With finances, with life, and with performances, that’s how I am, Wallenda says. “I’m all in. If I get knocked down, I’ll invest again until I win,” He says his career has afforded him the opportunity to retire comfortably, but he can’t imagine doing so.

“I’ve been extremely blessed, more than I ever dreamed,” he says. “I could retire now at 42, but my wife says I’m addicted to work.” Beyond wire walking, he and Erendira keep busy with different activities, like any normal family. “I do house remodeling. We buy and flip houses,” Wallenda says. “But when I’m doing that, I can’t wait till the next big walk.”

Air boxing and boxing-based fitness classes don’t involve sparring or the risk of getting clocked in the head. Jab, cross, uppercut, cross, cross.

Beginners may punch it out on a speed bag, learn proper form, and practice their footwork with conditioning drills while timing their moves to energetic music.

Noncontact boxing boasts virtues for anyone who wants to get stronger, fend off age-related cognitive decline, or improve hand-eye coordination—and feel exhilarated while doing it. According to experts at Rock Steady Boxing, a program that utilizes boxing training to combat Parkinson’s disease, a passion for shadowboxing can even help fight off certain neurological conditions.

“My students love boxing because they just feel so powerful,” says Leigh Anne Richards, who has a Master of Education degree in health and physical education and specializes in training people in midlife and older. She brought the Rock Steady Boxing program to Montgomery, Alabama, a few years ago.

“When you’re 50 and above, it’s not so much about how high you can jump or how much weight you can lift; it’s about functional fitness—being able to work in the yard, play with grandchildren, or carry boxes up to the attic,” she says.

Shadowboxing is safe for those with arthritis or osteoporosis while still getting your blood pumping and lifting your mood. Exercises that use bodyweight, such as boxing, strengthen and stabilize the muscles around joints and provide important weight-bearing exercise to stave off osteoporosis. Plus, the intense full-body workout that boxing provides uniquely connects body and mind in a way that can make you feel on top of the world.

Richards, 61, draws inspiration from seeing her clients transform themselves physically and mentally. One 85-year-old man, who used a walker and had a shuffling gait due to his condition, came to the class helped by a caregiver. With regular boxing practice, he gained increasing awareness of his balance, his foot placement, and weight distribution, and he learned to aim punches at a target with deliberation. Over time, his lost abilities began to return bit by bit.

“It was unbelievable, the progress he made. He started picking up his feet and walking [into the gym] ahead of his caregiver—and he stopped using the walker,” says Richards.

Another student, in his late 60s, had been a competitive cyclist in his earlier years, before Parkinson’s disease robbed him of mobility in one leg and caused him to hunch forward. “We work on everything that older adults need, including balance, gait, walking, and agility,” says Richards. “Boxing-based drills enabled him to gradually regain his posture and ease of movement, together with a class full of other people who were similarly giving it their all.” My students are all so attached to each other, and they are cheerleaders for each other, says Richards. “It is such a time of camaraderie.”

Benefits for Mind and Body

Medical research backs up the power of fitness boxing as a way for older adults to gain vitality, strength, and balance. “Balance issues are common with everyone who starts aging,” says Richards. “With boxing, we may have you stand on one foot, keep one leg up, or stand on a balance object while you hit the bag first with one hand and then the other, so you’re constantly challenging your balance.”

As a form of high-intensity interval training (HIIT), boxing involves swapping between short periods of going full tilt and then doing something low intensity. “We do a burst of punching as hard as you can for one minute, then switch to jumping jacks for 30 seconds,” says Richards. “High-intensity workouts have been shown to improve and delay the symptoms of Parkinson’s, but they’re also anti-aging for everybody.”

Amazingly, HIIT workouts appear to correct the decline in cellular health that naturally comes from aging, making muscle cells actually act younger, according to research from the esteemed Mayo Clinic. In fact, people in their mid-60s and older who did HIIT workouts for 12 weeks had more and healthier energy-producing mitochondria in their muscle cells compared to those who did other forms of exercise, such as riding a stationary bike at a moderate pace, The New York Times reported.

While the punches are intensely physical, the shifting patterns bring intense focus to the mind. When Richards calls out a series of punches by number—one, two, four, two, two—students have to concentrate and make their bodies respond.

“You’ve got to quickly process, what punch is a two? What is a four?” Richards says. “Other times, we put dots with numbers on the bag. While they look at the center dot, I’ll call out different numbers. That works the brain and promotes hand-eye coordination.”

With one student, a former certified public accountant whose abilities with numbers were slowed by Parkinson’s disease, Richards offered the number sequence in different ways to encourage the use of multiple neural pathways. She did this by having him listen to the numbers, read them from a whiteboard, and say them out loud, all while performing the punches.

Pushing hard with bursts of intense exercise beyond one’s comfort zone can increase dopamine production in the brain even more than medication, according to a Cleveland Clinic study of people with Parkinson’s disease. The research subjects that did this type of exercise enjoyed better motor function that persisted for four weeks. “It’s what they call forced exercise because you’re making yourself go harder than you normally would for a short time—unlike, for example, when you’re just walking,” says Richards.

Another part of youthfulness is having the hand-eye dexterity that lets you pick up tiny objects. Those fine motor skills begin to slip away as the brain ages, but hitting a speed bag or repeatedly reaching out to aim at a target is known for improving coordination and that can translate into increased ease when doing daily activities.

Getting Started

The popularity of fitness boxing has skyrocketed in recent years, and many gyms now offer different types of boxing classes for people of all fitness levels. To find a Rock Steady Boxing gym, which specifically serves those with a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, visit the website at rocksteadyboxing.org. There, you can find a gym by a zip code or city search.

You can also practice boxing at home, either with a fitness boxing video or some simple pieces of equipment from a sporting goods store or online retailer, says Richards. One of her favorite exercises uses a reflex ball, also called a boxing fight ball, which is basically a headband with a tennis ball attached by an elastic band. Professionals and beginners alike practice punching, dodging, and weaving for an addictive workout that burns calories and improves hand-eye coordination.

Those who want to spar with a spouse, friend, or grandchild can use a pair of boxing pads or focus mitts that one person wears on their hands while the other throws punches—as hard or lightly as you want—for a great way to work up a sweat and improve aim, accuracy, and timing.

Another piece of home equipment that gained popularity during the pandemic of the past year is a speed bag, which is just a light punching bag on a base that’s filled with sand or water. You can hit it with padded gloves, hand wraps, or your bare fists, and it springs back after each hit. There are also inflatable punching bags—reminiscent of the blow-up colorful clown versions that 1970s kids loved. With home boxing equipment like that, you’re sure to be a hit with any visiting grandchildren.

Kathy Waters, a wealth management financial advisor working in CAPTRUST’s Lake Success, New York, office, knows the circumstances all too well.

As her own mother’s cognitive mobility became impaired, Waters noticed the gas and water were sometimes left running in her home. “It wasn’t safe for her to live on her own anymore,” says Waters. “She had started to become a danger to herself and possibly to others.” The elder Waters was 89 years old when her family made the difficult decision to move her into an assisted living facility.

Choosing Wisely

Most of Waters’s clients only start to plan for long-term care once the loved one in question reaches 82 or thereabouts. But Waters says that whether you’re considering hiring aides or finding a long-term care facility, it involves a considerable amount of planning.

Ideally, she says the discussion of whether an individual should go to a facility or stay at home should happen closer to age 60 or 70. “Although it’s hard to face the fact that health problems may someday result in a loss of independence, if you begin planning now, there will be more options open in the future,” says Waters.

Of course, there are several key considerations when selecting a long-term care facility.

Waters suggests starting with recommendations from the hospital or doctor’s office and then from friends, relatives, social workers, and religious groups. Consider what is important to your loved one—nursing care, meals, physical therapy, activities and trips, religious services, location, hospice care, or special care such as for dementia. Once you’ve got your short list of choices established, here is what to consider next.

Quality of care. Waters recommends doing your homework by making sure that the nursing home or assisted living facility is certified by the state and asking to see the inspection report and certification of any safe facility you are considering. Ask about the credentials and training of the staff, including doctors, nurses, and aides. Can residents see their own doctors, or must they see the staff physician? Do they have access to dentists, eye doctors, and other specialists? Does the facility have clear procedures that it follows in medical emergencies?

You can get this and more information through Medicare’s Care Compare site, which uses a five-star rating system to help the public find and compare nursing homes, hospitals, and other providers. The website, medicare.gov/care-compare, includes an overall rating for each facility and separate scores based on health inspections, staffing, and quality measures.

Transportation. Arranging transportation for medical services can be a challenging process, especially for someone in a wheelchair or restricted to a bed. Waters says it can get complicated if a resident in assisted living needs to see a specialist, such as a urologist or cardiologist, or even needs to go for routine health checkups and the facility does not have people to escort them.

In fact, Waters tried something new last month when she called the neurologist’s office on behalf of her client. “I wanted to have the doctor go and speak to my client at her facility,” she says. “In this case, it did not work out, unfortunately.” It’s important to make sure you understand how transportation is arranged for nonemergency, routine, or unexpected medical services.

Location. Location is important for myriad reasons. It can affect how often an individual is visited by family and friends, which, in turn, affects the resident’s mental and emotional well-being. The right location can also help ensure quality-of-care issues are more easily addressed as problems arise. Moreover, proximity to things like religious services, shopping, socialization, and opportunities for outdoor activity can be important factors for your loved one.

Waters considered each of these components when choosing living arrangements for her mother. “I was able to join my mother for breakfast and dinner, and my brother came for lunch.”

Location isn’t everything to everyone, however. “Many clients rely on financial advisors to guide them, particularly around understanding what they can afford,” says Waters.

Cost. Waters helps her clients plan accordingly by either looking to purchase long-term care policies, which can be expensive, or doing estate planning and allocating money into Medicaid-protected trusts so they can go to a facility that is paid through Medicaid.

The major advantage to using income, savings, investments, and assets (such as your home) to pay for long-term care is that you have the most control over where and how you receive care.

Long-term care generally ranges between $6,000 and $12,000 a month nationwide, says Waters. In New York, Waters’s home base, nursing homes run from $15,000 to $20,000 a month. Full-time aides in your home can cost about $12,000 a month. Some facilities also offer a buy-in—where you actually buy the apartment. “It can be rather expensive,” Waters says. “One set of clients paid about $700,000.”

Safety and security. Ask when the facility was built or updated. In general, the newer the building, the more fire-resistant it will be due to changes in building codes. Look for safety features such as wide hallways, doors that unlock from the inside, handrails, and grab bars.

Healthcare aides and nursing home caregivers are compassionate people, but they are also among the lowest-paid healthcare professionals—and that makes some of them vulnerable to temptation. “You have to be cognizant of valuables,” says Waters. “Unfortunately, my mother’s wedding band was stolen.”

To some degree, Waters says, you can counter this temptation by making healthcare workers feel important and valued. “I tell them they are my eyes and ears; I’m counting on them to communicate to me.” Don’t make them feel like the hired help, she says. “Make them feel like a person who is respected for taking care of a loved one.”

While it can be difficult to take objects of sentimental value like a wedding ring or a special watch, if it’s of any monetary value, Waters recommends replacing it with something comparable but less expensive.

Soft aspects. What kinds of social and entertainment activities are planned for the residents? Is there a library? A place where residents can purchase personal items? Is there a safe place to enjoy the outdoors, such as an enclosed garden? Are meals served in a communal dining room or are residents served in their rooms?

You have to do your research and find the special extras unique to each facility, says Waters. “Some extras, such as medication management, are included in the monthly maintenance and some facilities bill separately for them.”

In Waters’s mother’s case, the family felt fortunate—a good friend’s mother lived at the same facility. “That was part of why I wanted my mother going there—she would know somebody,” says Waters.

“Many clients wish they could bring their parent into their home, but that’s rarely feasible,” says Waters. “So, we are fortunate that these long-term care facilities are available, and, overall, they do a good job providing care and entertainment for people who are very vulnerable.”

Many local and national caregiver support groups and community services are available to help you navigate the process of finding long-term care for yourself or for loved ones. If you don’t know where to find help, contact your state’s department of eldercare services. Or call 800.677.1116 to reach the Eldercare Locator, an information and referral service sponsored by the federal government that can direct you to resources available nationally or in your area.

If any of these scenarios seem familiar, you may be suffering from the malady known as FOMO—or fear of missing out. FOMO is a fear of regret, the fear that deciding not to do something is the wrong choice. It manifests itself in various ways, from a brief pang of envy to lingering self-doubt or increasing feelings of inadequacy, and it urges us toward short-term gain rather than long-term benefit.

Among other things, FOMO urges you to splurge on a trendy new toy of some kind because everyone else is getting one. And it is at work when you decide to chase a risky investment because it might be the next big thing.

To date, much of the research that explores the psychology of FOMO focuses on feelings of stress, anxiety, and negativity among young people. But the phenomenon is much more pervasive. It can affect people of all ages and domains of life beyond the social. In fact, 70 percent of adults in developed countries experience FOMO to some degree. We can’t stand missing out.

Me and Mrs. Jones

It’s interesting that FOMO could have snuck up on us like this. The word was only added to the Merriam-Webster dictionary in the same year as athleisure and bitcoin. FOMO is, of course, nothing new. As humans, we’re programmed to conform to society’s norms, and we feel insecure or disappointed if we’ve missed out on an opportunity that others have taken advantage of.

Before the smartphone era, “keeping up with the Joneses” pushed many Americans to mimic their neighbors’ lifestyles and standards of living through conspicuous consumption—driving the right car, wearing the right brands, attending the right schools, and joining the right clubs. But social media and real-time access to almost everything have turbocharged the concept.

Marketing strategist Dr. Dan Herman identified FOMO in 1996 and published the first academic paper on the topic in 2000. Herman observed the phenomenon during focus groups and interviews. He uncovered a common theme of interviewees’ fearful attitudes about the possibility of missing an opportunity—and the joy that would come from seizing it. Marketers have since weaponized Herman’s work with tactics such as limited-time free-shipping offers, early purchaser discounts, and celebrity and influencer testimonials.

Moderation in All Things

But FOMO is not all downsides. According to Herman, this phenomenon can lead us to “richer lives, filled with interest, excitement, and pleasures” and “motivate us to develop ourselves to the fullest extent and to reach achievements that reward us with feelings of satisfaction, might, and worth.”

Sounds a little like Don Draper, doesn’t it?

The fear embedded in FOMO urges us toward behaviors that make us more attractive and interesting to others, Herman says, so long as we learn to cope with it. He also found that the ability to cope well with that fear correlates with financial and social success and life satisfaction. So, while missing out is inevitable, the fear of missing out can be a good thing—in moderation.

Without moderation, FOMO can generate negative consequences. Sufferers can become anxious, overwhelmed, and unable to make rational decisions. They may shy away from commitments to career, a partner, or friends because they don’t want to close the door on other possibilities. FOMO can become a self-fulfilling prophecy for people who make short-term-focused decisions to quell their anxieties.

Beyond the emotional aspects, FOMO can encourage decisions with negative long-term financial consequences. These decisions may be small, like caving in and buying the latest 5G iPhone, or large, like trading in for a new car every few years so that you can have the latest and greatest features. What about buying the more expensive house—so you’ll have the extra space in case you need it? And, after all, it would be a shame to miss out on mortgage rates this low.

Trying to maintain status is a slippery slope, and this kind of lifestyle creep can erode finances over time.

The realm of investments is fraught with FOMO opportunities too, and with the stock market at all-time highs, you’re hearing about them every day—in the financial news, from friends, and maybe even from financial professionals. Technology stocks, special-purpose acquisition companies (SPACs), initial public offerings (IPOs), meme stocks, and cryptocurrencies are making headlines with their eye-popping returns and are causing many investors to make short-term, risky, FOMO-induced decisions.

While somebody is certainly making money from these manias, too often, most end up with losses.

Free Your Mind

So how can you protect yourself from FOMO—or, at least, moderate its influence on your life and big financial decisions?

As is often the case when fighting behavioral biases, the first step in preempting the effects of FOMO is realizing exactly what is going on—noticing, perhaps, that you are not altogether in control of your thinking. In fact, you may not be thinking at all.

This is because the brain’s first response to fear is generated by the amygdala, a small, almond-shaped structure deep in the brain. The amygdala is a primal part of our brain that generates a stress reaction in the body when it perceives a threat to your survival. The threat could be a lion pouncing or something more subtle— for example, when you feel like you’re not part of the group or that you’re not in possession of critical information. In other words, fearing you’re missing out.

Stressed and fearful is not a good mindset for making sound decisions, but fear not (pun intended). It’s easy to engage other parts of your brain that can be more helpful. Simply call a timeout and ask yourself: Is this decision necessary for my long-term well-being—or is it a short-term reaction driven by anxiety and fear that a great opportunity is slipping away?

The question alone will activate parts of your brain responsible for rational thinking, most notably your pre-frontal cortex. If the decision you’re trying to make is a big financial decision, you’ll want to speak with your financial and tax advisors. From there, you can use a range of strategies to guide your decision. Talk to a trusted friend or family member, or follow in the footsteps of Ben Franklin.

Franklin’s decision-making method, described in his Autobiography, published in 1791, involves capturing the pros and cons of prospective decisions in a T-chart and scoring them by applying weights to the factors. His approach slows you down because, as he said in a letter to a friend, “all the Reasons pro and con are not present to the Mind at the same time.”

Psychologists suggest a range of tactics—from practicing meditation and accepting yourself as you are to expressing gratitude and focusing on the important relationships in your life—as powerful antidotes to FOMO.

Despite its new-kid-on-the-block status, it appears that FOMO is here to stay, fueled by social media, the Internet, real-time access to all kinds of news and information, and the general immediacy of life in the 21st century. In fact, it probably only gets worse from here—unless we take steps to rein it in.

His days are packed with emotional conversations, prayers, and acts of kindness for patients and their families as they confront all kinds of loss, including serious illness and death.

“Each day, people surprise and inspire me with their courage, their humor, their generosity, their grace, and their love,” O’Neal says. “The work is uplifting.”

He felt called to this ministry after reinventing himself several times during his business career. “Since I was a kid, I have always thought that life is about adventure. I have always been looking for the next adventure,” O’Neal says.

“Being back in the hospital is a kind of coming home for me,” O’Neal says. “I was pre-med as an undergraduate, and I had worked in Washington, D.C.-area hospitals as an orderly and then as a surgical assistant.” When he didn’t get accepted into medical school, he found industrial chemical sales a natural fit. He had success there and was recruited at a young age to be a sales manager in a small company.

Recognizing that business would be his career for a while, he earned a Master of Business Administration degree from the Kenan-Flagler Business School at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. From there, he went to Northern Telecom and then to the American Social Health Association, where he helped get the National AIDS Hotline up and running.

But O’Neal missed his roots in the natural sciences and, after several years, found his way into the environmental consulting field, specifically around ambient air quality. He and his colleagues at a small firm in Chapel Hill guided sections of industry on air quality science, policy, and regulations. Seeking a solid foundation in the field, he went to graduate school and earned a Master of Science degree in environmental science. In his final role before becoming a chaplain, he was a project manager on a hydrological forecasting project in Eastern Europe.

Turning an Avocation into a Vocation

While juggling demanding careers and raising three children with his wife, Janice Whitaker, O’Neal participated in pastoral care work with his church, Christ Episcopal, in downtown Raleigh. One of these pastoral care roles was that of Eucharistic Visitor, where laypeople take the Eucharist to those who are homebound or in the hospital.

“I think I wore the rector out with my unending stories about ‘how powerful this seems, how meaningful it was to me and to those I minister to.’ He suggested I investigate clinical pastoral education (CPE) at one of the local hospitals. I hemmed and hawed for about a year,” O’Neal says.

Finally, he had the opportunity to talk with a veteran hospital supervising chaplain. About 20 minutes into their conversation, she said, “Jesse, you know what your problem is? You are afraid you are going to get into this, and you are going to fall in love with this work. Then, what will you do?”

He accepted the challenge and took his first CPE training at WakeMed during the summer of 2014.

“I did fall in love with the work,” O’Neal says. “I fell hard.” His first internship with WakeMed’s Clinical Pastoral Education Program led to a second and then a yearlong chaplain residency.

The timing was right. His three children were grown, his wife had retired from a successful career as an executive with a pharmaceutical company, and they had saved well.

“Emotionally, I don’t think I could have done this in my 20s or 30s, maybe not even in my 40s or 50s, because I hadn’t accumulated the life experience that supports me in the work,” O’Neal says.

He draws on his project management experience for his new field. “There are lots of ways to be successful as a project manager,” O’Neal says. “My style was to be aware of and invest in the emotional dimensions of the team, hoping to understand what keeps them moving forward and what holds them back,” he says. “Knowing them emotionally was a dimension of that.”

He says, now, instead of caring about people as an adjunct of the work, caring for people is the work.

Like his other endeavors, O’Neal wanted to be sure he was well trained for his new career, so he recently completed his Master of Arts degree in pastoral and spiritual care at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver. Before COVID-19 hit, he traveled to Denver for several days each 10-week quarter for in-person classes. Under COVID-19 restrictions over the past year, all hybrid classes have become completely online.

Finding Those in Need

Every day is unique for a hospital chaplain. O’Neal leans on emergency room nurses, whom he calls “absolute rock stars,” for guidance on where the pastoral needs might be.

He often meets with patients who have had heart attacks, strokes, or other serious illnesses. He also meets with the patients’ families to help them negotiate their feelings as well as hospital procedures.

Once family members arrive, he stays with them. In all these situations, there is loss: loss of function, loss of capabilities, and, sometimes, loss of life, O’Neal says. “My job is to provide the emotional and spiritual support that allows them to initiate their grieving process.”

“When people lose a loved one, their grief can be overwhelming. The reason people grieve is that they had the courage to love as if that love could last forever. I appreciate that courage. And I want to be around people who have that kind of courage,” O’Neal says.

When they’re grieving, they’re coming to terms with the reality that this grief is going to be with them in some form forever, he says. “When you live in a world that has great love, you also live in a world that has great grief.”

Being there is important, O’Neal says. “I cannot ever fully understand the suffering of another human being, the depth and the texture of their suffering,” O’Neal says. “They are on their own unique path through this world. I don’t know what their suffering can or should mean in this journey.”

Although he doesn’t leave anyone’s side during difficult times, he knows it’s a process that people have to go through themselves with the help of their families, friends, and beliefs. “They have to find emotional traction. They have to find something that allows them to get through to the next minute, and the next, and the next,” O’Neal says.

“When our kindred humans, in the face of devastating grief, find that inner resolve that their life can go on, that their life must go on, and gather their family and their love and leave the hospital burdened with grief, but strengthened by hope, this fills me with wonder,” O’Neal says. “I cannot explain it without God.”

Unfortunately, comforting people with physical touch hasn’t been possible this past year because of COVID-19. Everyone keeps the recommended distance, says O’Neal, and hugging has been replaced with elbow bumping.

O’Neal says physical touch is very important, and it can be reassuring to everyone. “I am a hugger, but, during COVID, we try to keep our distance,” he says.

Offering Company to Others

When he has time, O’Neal does what he calls “cold calls,” visiting patients and their families throughout the hospital dealing with less serious conditions.

Sometimes, these visits and conversations last for five minutes. Sometimes, they are an hour long. “I never know where conversations are going,” says O’Neal. “I try to be receptive to where the patient or family wants to go.”

During the visit, O’Neal usually learns something about the person’s faith. “Some people want to immediately open that door and want spiritual and emotional support, and some don’t.”

Often, the conversations lead to a request for prayer. “I do that with great delight. I am in prayer multiple times a day, really continually throughout the day, which is a great joy to me,” O’Neal says.

He lets patients initiate prayer requests. Sometimes, the requests come in as O’Neal is leaving the room and he asks them, “Is there anything else I can do for you today?” They might look at him and look at his badge and say, “Well, you are a chaplain. You could pray for us?”

“I can never predict what people want me to pray about. Sometimes, they’ll ask to pray about healing or good results for a test they’ve had.” But sometimes, their prayer requests catch him by surprise.

In one case, the patient said, “I have been lying here for the last couple hours, and I can see that the people working here are good people. They have been exposed to all kinds of risks in the last year. I want you to pray for them.”

Another patient spent an hour explaining why he was an atheist. As O’Neal was leaving, the patient said, “You’re a chaplain. Aren’t you going to pray for me?”

He did.

Often patients repay him in kind. “I can’t count the times patients have prayed for me and over me,” O’Neal says. “They lift me up with their humor, resiliency, and grace. It would fill up your heart to the breaking point.”

O’Neal has been trained to minister to people of every faith, including those who are Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, and Hindu.

One day, early in the pandemic, he stopped to talk to a Hindu woman. She was quietly weeping against a wall in the emergency department because visitation was so constrained. O’Neal asked how he could be of assistance. “Would you pray for me?” she asked.

He told her he knew a little about Hinduism, but he didn’t know how to pray in her faith. She said to him, “You just pray how you pray. That will be enough.”

Giving It All He’s Got

O’Neal is in awe of his medical colleagues. “I feel extremely grateful to be working with rock stars every single day. If you could see what this team is able to accomplish with their clinical skills and their compassion, it would touch your heart,” O’Neal says.

“I believe in the mission of WakeMed,” says O’Neal. “It’s an extraordinary place that began as a community hospital in the 1960s, with a mission of serving all. It has grown and expanded and is regularly mentioned in the same sentence as the well-known university-based hospitals in the area.”

His wife, Janice, says, “Jesse has been successful in various business roles but never as fulfilled as in the chaplaincy work. Each day, he feels that he’s making a difference by helping patients and families, some of whom are experiencing the most difficult times in their lives. “He is a compassionate extrovert who is able to sense what people need and how to help them,” she says. “He loves his work and has found his calling.”

His daughter, Meaghan O’Neal Woodhouse, adds, “If I or one of my loved ones had to be in the emergency department, I would want someone like my dad there to help support us through the process.”

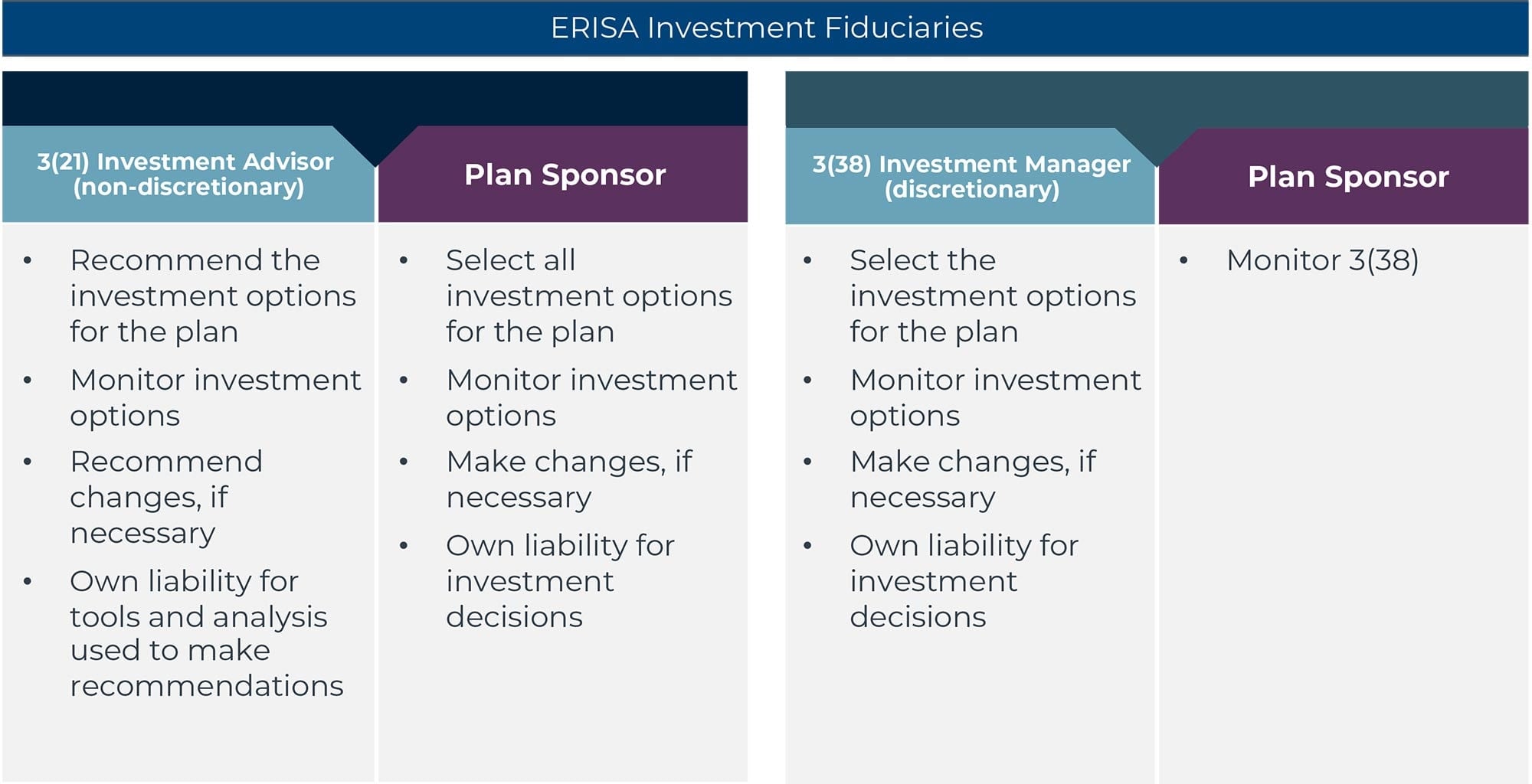

Although similarly named, 3(21) investment advisors and 3(38) investment managers under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) are quite different. They provide different services and levels of protection and entail different plan sponsor responsibilities.

ERISA defines a fiduciary as a person involved with plan administration, a person with control over plan assets, or a person who gives investment advice regarding plan assets. Plan sponsors often engage investment advisors to assist with their fiduciary responsibilities if they do not possess the required expertise internally.

When sponsors engage investment advisors to assist with their fiduciary duties, these arrangements are referred to as 3(21) or co-fiduciary engagements. In a 3(21) relationship, the advisor is responsible for investment recommendations made to the plan sponsor, but ultimately the authority to direct assets and the fiduciary responsibility of those investment decisions falls to the plan sponsor.

Alternatively, in a 3(38) engagement, the plan sponsor delegates the decision-making authority regarding investments to the 3(38) investment manager. An appropriately structured 3(38) engagement frees the plan sponsor from the time involved in the selection and monitoring of plan investments and from the liability of those decisions. In a 3(38) arrangement, the plan sponsor’s singular investment-related fiduciary responsibility is the selection and monitoring of the 3(38) investment manager.

Sounds complicated, right? It’s not. Take a look at Figure One, which breaks down 3(21) investment advisor and 3(38) investment manager roles at a high level.

Figure One: Understanding 3(21) Investment Advisors and 3(38) Investment Managers

3(38): Simple and Effective

Many retirement plan sponsors are looking to spend less time on plan investments so they can focus on other aspects of plan management, such as providing participants with the resources they need to help them get in the plan and saving more. One way to do this is by outsourcing investment decision making to a qualified 3(38) investment manager.

But, while hiring a 3(38) investment manager is a simple and effective way to help reduce fiduciary risk, it doesn’t mean all fiduciary duties are eliminated. The process of selecting and engaging a 3(38) investment manager itself is a fiduciary responsibility and comes with some ongoing work. For example, plan sponsors are expected to monitor 3(38) investment managers as they would any other service provider.

“But the thing you monitor is not [the same as] second-guessing their decisions,” says Jenny Eller, chair of Groom Law Group’s Retirement Services Practice Group and Fiduciary Practice. “You monitor their process: Do they continue to have qualified people involved in the process? Do they continue to have the resources they need to engage in their own kind of prudent process?” You don’t get to pick a 3(38) investment manager and set it and forget it, Eller says. “You have to continue to monitor them.”

Unfortunately, it’s not unusual for things to fall through the cracks, even for the most meticulous plan sponsors. But those missteps are avoidable. From understanding what is going to be in or out of scope to making the most of the labor savings plan sponsors hope to recover—in this article, CAPTRUST leans on industry experts to expose some of the most common pitfalls when selecting or working with a 3(38) investment manager and how to avoid them.

Pitfall #1: No Ongoing Formal Monitoring Process

“The law provides a very special benefit for [plan sponsors] who hire a 3(38) investment manager,” Eller says. As long as the plan sponsor has a solid process for selecting and monitoring the 3(38) investment manager, the plan sponsor will not be liable for losses that the 3(38) investment manager causes the plan, she says. Here are a few ways plan sponsors can approach the fiduciary duty of monitoring a 3(38) investment manager’s process.

Keep tabs. “We’re starting to see lawsuits pop up where participants are saying plan sponsors were not paying attention—that a 3(38) investment manager was hired, but the plan sponsor was not asking any questions, or monitoring their process,” Jennifer Doss, senior director of CAPTRUST’s defined contribution practice, says. Maintain a record of your ongoing monitoring process. Take notes. “Because if it’s not documented somewhere, it never happened,” she says. Look for 3(38) investment managers that can provide good documentation for your files.

Ask some hard questions. Plan sponsors should periodically perform due diligence on their 3(38) investment manager. Employers and plan sponsors may want to do a regular request for information (RFI) or questionnaire. This plan sponsor due diligence is intended to verify that there haven’t been any changes to the organization that could affect its ability to fulfill its duties as 3(38) investment manager. This might include changes to its leadership team or ownership and if the firm has, or has not, been subject to a lawsuit or judgement.

Think about the questionnaire as an opportunity to get insight on the firm. Make a point to connect with your 3(38) investment manager on any changes to the investment philosophy of the firm or personnel changes of those making the 3(38) investment decisions for your plan. Experts say plan sponsors may also look to Form ADV for answers—and we’ll get into those details in just a bit. First, let’s talk about the plan sponsors role when contracting with a 3(38) investment manager.

Pitfall #2: Contracting with a 3(38) Investment Manager but Acting in a 3(21) Investment Advisor Capacity

When a plan sponsor engages a 3(38) investment manager, they give up control of the plan’s investment decision-making process. In a defined contribution plan, this means the 3(38) investment manager has full discretion to select, monitor, remove, and replace investment options offered to plan participants. But it’s important that plan committees who utilize a 3(38) investment manager maximize that benefit, Eller says.

Make the most of it. Get the labor savings you intended to get. A 3(38) investment manager is legally required to act in its clients’ best interests when it comes to choosing funds and managing assets. So go do other things! Having someone else manage plan investments allows plan sponsors time to focus on participant engagement, plan design, optimization of other plan vendors—like employee education and financial wellness providers—and overall participant satisfaction or retirement readiness. Don’t squander it.

Don’t forfeit fiduciary protection. Plan sponsor influence over investment decisions comes with potential liability when dealing with ERISA investment management and oversight. “If you hire a 3(38) [investment manager] and then push them out of the way and make the decisions anyway, you have lost all benefits of appointing [the 3(38) investment manager],” Eller says. For example, if the 3(38) investment manager allows the plan sponsor to remain heavily involved in the investment decisions for the plan—whether that is suggesting or influencing the funds in the plan lineup—there is a risk that the plan sponsor loses the fiduciary protection that hiring the 3(38) investment manager is meant to provide.

“It can be difficult for some plan sponsors to pass the reins,” Doss says. Some want to retain the ultimate decision about which funds should be offered, which isn’t possible in a true 3(38) relationship.

Pitfall #3: Allowing Room for Guesswork or Interpretation

The details of a 3(38) investment manager relationship are not something to leave to chance, so do your homework.

Ask about any potential conflicts of interest. One best practice is to make sure your 3(38) investment manager discloses all sources of revenue related to the relationship, says Martha Tejera, founder of Tejera & Associates, a consulting firm helping employers meet their fiduciary responsibility in the selection of their retirement plan providers and advisors.