When CAPTRUST Chief Executive Officer Fielding Miller decided it was time for CAPTRUST to retool the way it communicates with clients, he knew what direction he wanted things to go. And exactly who to call on to get there.

Enter Chief Marketing Officer John Curry.

Curry’s signature salt-and-pepper coif of long, wavy hair stands out among CAPTRUST senior leadership, but he pulls it off. Curry compensates, in part, with his slant toward impeccable dress. Perhaps his colleagues would expect no less from him. He is, quite possibly, a double agent.

This 30-year industry veteran is not only CAPTRUST’s head of marketing, he is also the rhythm guitarist in the company’s in-house garage rock band, The Rollovers.

Like Curry, VESTED magazine—his brainchild and ongoing passion project—stands out among financial firms’ cookie-cutter newsletters and stock market updates.

Four years since inception, VESTED is undeniably making a difference in the lives of its more than 20,000 print and digital readers. Its Second Act heroes are lighting a path for those seeking new directions; its planning and lifestyle features, Passion Pursuits, Expert Angle, and Lasting Legacy columns (among others) explore nontraditional aspects of retirement—often told through the stories of those who have been there and done that.

I’ve got this marketing ninja for a lunchtime interview and deep dive on the magazine: what it’s all about, why we love it, and where it’s going next.

Let’s start with the basics. What is VESTED about? What is CAPTRUST trying to do with VESTED?

When we started VESTED, it was helpful to know that we didn’t want it to be about money and markets. You can get that in lots of places. We also believed—and still do—that that kind of information is not very helpful, and it’s not going to help anyone live a better life. In fact, it may fuel bad behaviors, like knee-jerk reactions to market moves, market timing, or chasing what’s hot.

That freed us up to go elsewhere. We decided that VESTED’s mission would be to inform and inspire what’s next for our readers. With all the doom and gloom we hear in the retirement industry about the looming retirement crisis, we liked the idea of an aspirational mission. We also wanted it to be full of people.

CAPTRUST is a financial services firm. Why create a magazine?

I get this question a lot.

We wanted to do something different. In a world that is moving increasingly digital, we thought there was an opportunity to put something in the hands of our clients and friends that is tangible and beautiful. The tactile aspect of VESTED is very important. It’s the weight of the paper and the coating on the cover. People always comment on the quality of the magazine itself.

VESTED’s content is different, too. We wanted to write about topics relevant to our clients’ lives. Topics that are helpful to them. We use VESTED as a way to put new ideas and possibilities for what’s next in front of them.

What’s next could be noncareer work, a new career, travel, exploring passions, learning, coping with aging, downsizing, a big family project, or thinking about legacy, to name just a few. These are hot topics for our readers, and there are not many good sources for perspective on them. A lot of our articles pull together resources from multiple sources—books, the web, TED Talks, subject matter experts—to help frame an issue or topic and provide tips for getting started if the topic resonates with them.

We spend a lot of time writing about retirement—if that’s the right word for it. We hear from clients that it’s an intimidating process, and it’s something they are uncertain about. We want to help. CAPTRUST has the experience and expertise to give our readers tips to help them achieve a more successful retirement. Often, VESTED tries to do that through the stories and lessons of people who have paved the way.

What did it take to make the magazine go from an idea to a reality?

[CEO] Fielding [Miller] and I were in the car on the way to a meeting. We got to talking about the state of our client communications—what they were and what they could be. We both wanted CAPTRUST’s brand to be more aspirational, more evergreen, and more focused on helping people realize their potential as they enter retirement.

We came up with the idea to make a magazine. When we got back to the office, I immediately went up the elevator, called everybody in marketing into a conference room, and basically said, “Holy crap! Fielding wants us to create a magazine. What do we do now?”

That was August 2014. The first issue came out in January of 2015. So you can imagine that, during those five months, we were doing everything from trying to conceive what this magazine should be, what it should look like, the paper size, the paper weight, the coatings, the regular columns and features, who the writers would be, printing, shipping, editorial voice, and featured talent. You name it. We had to decide on literally every aspect of what it takes to make a magazine. It was a lot of fun.

Tell me about VESTED’s target audience and how you landed on this demographic.

Our readers tend to be in their mid-to-late 50s or early 60s, around retirement age—maybe a few years before or a few years into retirement—who have saved and invested well. They are thinking about what’s next for their lives. We want to help this group understand what they need to know to retire successfully. We can show them some of the path forward and provide an opportunity to think differently about it.

What do you see for the future of VESTED?

So much. The magazine has really caught fire. I think there is an opportunity to extend VESTED into video, which is something we have experimented with in the past.

We also want to create a live, in-person VESTED event, in the form of a symposium that we can execute around the country. We’re interested in what we can do that will put us in touch with people in and around the markets we serve. VESTED is really becoming the CAPTRUST brand when it comes to value-added content for wealth management clients.

Where do you see yourself 10 years from now?

VESTED is the single most interesting and exciting project I’ve worked on in my 30-plus-year career. I’m in no rush to go anywhere. I’d love to still be working on VESTED 10 years from now. Maybe they’ll let me stay on as an editor and weigh in on art direction. If Fielding doesn’t mind me working out of my home in Spain, I don’t see a reason to stop.

What about your work inspires you?

Three decades in the financial services industry—mostly focused on retirement issues—and I’ve become very passionate about helping America retire successfully. And, of course, my wife, Marcela, is also in the industry, so it’s a team effort.

I also think about the work we do on a very personal basis. I always think about our clients, who, if they take our advice, can find themselves in a comfortable financial position. When they get to the point of retirement—or time to do something different—I want them to be excited about the possibilities and ready to explore the world. It would be a real shame if they didn’t get to enjoy the fruits of their financial success. And it’s easy to see why they wouldn’t.

If you’re a good saver, you may not know how to spend your money in retirement. Or you may not know where to start to engage in that conversation. One of the goals of VESTED is to give our readers a little jumpstart and show them how to think about it. We present ideas we hope readers will explore. I like to imagine that we are seeding interesting dinner-table conversations they will be having with their spouses or friends about their futures.

When did you realize you had an interest in writing?

When I got to CAPTRUST, I thought I was a pretty good writer. But I quickly found out I was in over my head. And I realized that, as head of the marketing department, the buck stopped with me. And so, I needed to get serious about it. I needed to become a student of the game. I needed to practice, and I needed to own it.

I don’t know if I’ve gotten better, but it certainly has gotten easier. In the process, I’ve come to enjoy it, and that’s why I obsess over things like grammar, writing standards, tone, and voice.

What is your favorite thing about being editor in chief for VESTED?

The people I work with on the VESTED editorial and design teams are great. And I love challenging them to think big, to make sure that the magazine is as great as it can be. Making sure it fulfills our vision is hard. Great stuff doesn’t happen by accident.

But I also love meeting the people who are featured in our magazine. They are world-class, fascinating people. By the time we do our photoshoots, I have looked at everything I can find on them. I have read all their books, read every magazine article about them, listened to podcasts they are featured on—you name it. By then, I’ve turned into a complete fanboy. It’s a bit embarrassing.

Meeting Jamal Joseph—the Second Act subject of the last issue—is definitely a highlight. I had been editing the story while reading his book, Panther Baby. Then we went to Harlem for the photoshoot. My job at a photoshoot is mostly to make the person we are photographing feel at ease and to stay out of the way. I have to admit I was a little awestruck. When I finally got going, it was great. He is a super-warm and engaging guy.

What advice would you give someone embarking on a big professional project?

Challenge yourself. The only thing that’s ever standing in your way is your preconceptions about yourself.

One day your boss’s boss is going to walk into your office and tell you to put a man on the moon. When that happens, don’t come up with 20 reasons why you can’t put a man on the moon, or why it’s scary to put a man on the moon, or why you might fail. Embrace it and put a man on the moon! How many of those opportunities do you get? So, run with it. That’s what I would tell them.

A big thank you to John Curry for spending some time with me. He is a cerebral gentleman, a pleasure to interview, and proof that rock-and-roll hair has a place in a pinstriped suit.

The billboard, sponsored by the Greater Boston Food Bank, said, “One in six Americans are hungry.” Rauch’s first thought was, “That just can’t be right.” As former national president of the Trader Joe’s grocery chain who guided its expansion from nine stores in Southern California to more than 400 stores nationwide, he knew we were in a land of plenty. In fact, from farm to fridge, we waste up to 40 percent of the food we produce, enough to fill the Rose Bowl every day. So why do nearly 50 million Americans struggle to put meals on the table?

“Having spent my career in the food industry, I knew that America had more than enough food to feed everyone,” Rauch says. “So why weren’t we? This started me down the road of discovery about the real nature of hunger in America and what we can do about it.”

That road led him to create the Daily Table grocery stores in the Dorchester and Roxbury neighborhoods of Boston. Daily Table addresses the paradoxical dual challenges of hunger and obesity by providing convenient, healthy, and surprisingly affordable food. “Think of us like a T.J. Maxx or Marshalls for food,” states the nonprofit’s website.

The food is donated or deeply discounted from well-known brands and local growers, national distributors, and nearby retailers. The food could be surplus, approaching expiration date, or imperfect in appearance. It’s food that would otherwise be destined for a landfill.

Now in its fourth year, Daily Table moves about a million nutritional servings a month into the community. That’s a million servings not coming from a vending machine, a convenience store, or a burger griddle. It’s a million steps toward a community’s healthier living, at fast food prices or less.

“Our intention wasn’t to be just a grocery store,” said Rauch. “We are a 501(c)(3) nonprofit because we are dedicated to relieving hunger and food insecurity and raising the community’s health. And we do that by masquerading as a food market.”

The Accidental Grocer

After earning a Bachelor of Arts degree in history and then waiting to hear back about graduate school, Rauch was at a crossroads. A friend who was general manager of the natural food store Erewhon tried to persuade him to come work in his company’s distribution center.

“That didn’t sound very appealing to me,” Rauch recalls. “But this was the ’70s, and the company was filled with bright-eyed, idealistic, optimistic people who were excited about food systems in the world. I thought, wow, this is an interesting group of people.” A stint with this pioneering company would fill the gap until grad school.

But he stayed and became vice president and general manager. “In the process, I started selling Erewhon products through this funny retail chain in Southern California called Trader Joe’s Pronto Market.” At the time, the markets looked like any 7-Eleven, the shelves lined with Wonder Bread, Hostess snacks, Campbell’s soup, soda, and cigarettes.

When Erewhon’s West Coast division was sold, Rauch thought about Trader Joe’s. “I had always loved interacting with the company. They were incredibly available. When I called Trader Joe’s, no one screened the call, asking who’s calling, what’s this in regard to, or is he expecting the call. If [founder] Joe Coulombe was around, someone found him and put him on the phone. I really liked that.”

This was 1977, and Trader Joe’s needed a new raison d’être. Competing with 7-Eleven was not the way forward. One differentiator was that Trader Joe’s had a successful private-label wine business, offering its own Charles Shaw wines for $1.99—“two-buck Chuck”—compared to other popular wines at $5, $6, or $7 a bottle. That model was working. Alcohol sales far surpassed food sales.

Why not do the same for food? “I spent the next year or two working with Joe to formulate the private-label program at Trader Joe’s, basically reinventing how customers think about store brands,” said Rauch. “Up until that point, ‘private label’ was just a price point, cheaper and lower quality than national brands. We turned that around and started creating destination products that were distinctive, unique, or priced significantly lower than the national brand.” The concept worked. Within 10 years, food revenues surpassed alcohol, and Trader Joe’s was poised to become a wildly successful grocery chain.

“I woke up one morning, and I had been with the company about 12 years, and I suddenly realized this is my career,” Rauch recalls with a chuckle. “I was kind of doing this while waiting to figure out what to do with my life. Suddenly I realized, I’m a grocer. How did that happen? It is a great place, with great people, very entrepreneurial, very innovative. It was a really fun, engaging, exciting place to work. Still is.”

Nudged by Coulombe, who was a big fan of business guru Peter Drucker, Rauch got his Executive Master of Business Administration degree at nearby Claremont Graduate University. “When I graduated from Drucker School of Management, the executive team at Trader Joe’s said, ‘You’re the new smarty pants business guy. You’re going to write the business plan for how we’ll grow outside of California.’”

The rest is a case study of which MBA students dream. Between 1990 and 2001, the number of stores quintupled, and profits soared tenfold. In 2008, Trader Joe’s had the highest sales per square foot of any grocer in the country, according to BusinessWeek. At the same time, Ethisphere magazine listed Trader Joe’s among its most ethical companies in the U.S.

But for Rauch, it was the right time for a change.

Graduating, Not Retiring

“It was 2008; I was 56, soon to be 57, and I had been traveling extensively with Trader Joe’s, particularly with all the expansions, opening up all the new stores,” said Rauch. “And, frankly, I wasn’t having the fun I was having before. It was a very different business. I remember going to Minneapolis in January, when it was minus 10 degrees, to look at a patch of dirt that was going to be a new store. I thought, ‘This isn’t fun.’ The ceaseless travel and the management side of the business lost its appeal for me.”

According to Rauch, the puzzles and challenges of creating a private-label program, nurturing a distinctive culture and product portfolio, scaling a nine-store chain to compete with behemoths such as Ralphs and Vons—those things were heady, but now it was time for something else.

“I didn’t know what that looked like. I had no idea what I was going to do,” said Rauch. “But I wasn’t going to call it retirement.”

Rauch spent the next year and a half doing some consulting, serving on boards and as a trustee for the top-ranked Olin College of Engineering. “Pretty quickly, I determined I wasn’t going to be satisfied just sitting on boards. A lot of it is just not as operationally satisfying for someone who had spent his life as an operator.”

An Encore Career for Social Good

A colleague at Olin told Rauch about a new Advanced Leadership Initiative at Harvard. Distinguished business professor and author Rosabeth Moss Kanter had created a program to help leaders at the top of their fields apply their skills to national and global social issues in their next life stage, particularly relating to health and welfare, children, and the environment. The first session was underway. A Boston Globe article sealed the deal for Rauch. This was the next step.

“What attracted me was the concept of taking people who had completed their primary careers but still had gas in the tank—10 to 15 years or longer to still be actively engaged—and let them have the use of the college, all the schools, working with faculty and students—to figure out how to tackle some major social ills,” said Rauch. “Then it hit me. This isn’t about learning, this is about doing. This is about taking your lifetime experience and adding some knowledge and information to social enterprise.”

Then came the billboard—one in six Americans hungry in a land of plenty, including plenty of waste. Rauch reflected on our dysfunctional food culture.

Earlier generations had experienced food scarcity through economic depressions, wartimes, and crop failures in the era before electricity and refrigeration. Baby boomers could be the first generation that took abundance for granted.

“At first I was thinking, it’s just a distribution issue, a logistical question. I thought I could help with that, but it turned out it wasn’t that. You’d better really understand what the problem is if you’re trying to solve it. Otherwise you’re going to come up with some elegant and beautiful solutions to the wrong problem,” says Rauch.

Nutrition with Dignity

“Generally speaking, people who are struggling economically can’t afford fresh fruit and vegetables, so they end up eating high-sugar, highly processed empty calories—junk food, if you will,” says Rauch. “So, the solution isn’t what I thought it was. It isn’t about distribution bottlenecks. They’ve already got a full stomach. We’ve got to get them a healthy meal.”

“That turns out to be complicated, because low-value calories such as corn and high fructose corn syrup are cheap. Nutrients are expensive. So, the question became, how can we afford to provide fruits and vegetables in an economically viable manner?”

Why not launch a massive fundraising effort and create another food bank? Food banks fill a critical need. For instance, Feeding America—the third-largest U.S. charity—feeds more than 46 million people through its vast network of food pantries, soup kitchens, shelters, and other community-based agencies.

However, a Feeding America leader told Rauch that many people who qualify for food charities don’t use them. Why? Is it transportation, immigration concerns, or language barriers?

“It turns out it’s much simpler than that. They’re ashamed, embarrassed. They don’t want a handout. That was a big awakening. Many people would rather keep their dignity than their health. I realized if we’re going to solve this problem at scale, we had to come up with a way that the person in need has a dignified exchange,” says Rauch.

“A handout sets up an imbalance,” says Rauch. “If we’re selling the product, even if it’s for pennies on the dollar, people are going to interact with us in a very different way. In that dynamic, they hold the power of the purse; they end up, by definition, having a sense of agency and dignity.”

Friendly Retail Stores

The Dorchester Daily Table store opened in June 2015, followed by a second location in nearby Roxbury. Membership is free, and Daily Table currently has 42,000 members. Rauch is scouting for third and fourth locations—and eyeing expansion into other states.

The stores offer an upbeat, clean, and friendly retail environment. Hand-lettered signs add a vintage market feel. The aisles and crates are brimming with fresh, healthy food options at budget-friendly prices: a pound of bananas for 29 cents, a can of tuna for 55 cents, or a dozen eggs for $1.19.

Instead of a burger and fries, busy customers can choose a nutritionist-approved dinner of two pieces of chicken, brown rice, and vegetables for $1.99 or pick up ready-to-cook and grab-n-go prepared meals. A teaching kitchen offers free cooking classes several days a week. More than 100 educational modules show members how to have food be tasty, nutritious, and healing.

“I don’t think you’ll find any place in Massachusetts where you can get a prepared meal with the recommended nutritional values for $1.99,” said Rauch. “It’s made possible because Daily Table works with a broad network of suppliers who offer donations and special buying opportunities. Food that might otherwise go to waste is now crafted into meal options that compete with unhealthy fast food options.”

Nutrition by Design

Rauch worked with a task force of nutritionists to quantify “healthy” to guide food decisions. For the last four years, Daily Table has met or exceeded these guidelines in food prepared in-house and purchased and donated food items. The stores do not even sell soda.

In 2017, the head of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) visited Daily Table along with an entourage of U.S. Department of Agriculture representatives. He declared Daily Table to be one of the only stores where food stamp recipients can get the 2,000 calories a day of nutritious food they should be eating and still have money in their pockets at the end of the month.

“We’re very proud of that, because for us, it’s the litmus test of how well we are meeting our mission of delivering nutrition at an affordable value,” says Rauch.

The Bottom Line

While Rauch would love for Daily Table to be self-sustaining, it does rely on monetary and in-kind donations. “I don’t care if you’re Walmart or Costco, you can’t bend the cost curve enough to have nutritious food compete with junk food. You can’t get fruits and vegetables to be as cheap as sugary, processed food,” says Rauch.

About 20 to 30 percent of merchandise is donated; the rest is purchased at discounts. Daily Table also relies on 200 to 300 hours a week from volunteers working alongside 60 employees hired from the local community who are paid 25 percent more than local minimum wage.

“We cover about two-thirds of our expenses from our own generated revenue, but we hope with more stores—and we are fundraising to open additional stores—we can come close to breaking even,” says Rauch. When the economics are viable, the hope is to expand the mission across the country.

For Jane Ehrman, now 68, a life-defining crisis came when she was a 37-year-old mother diagnosed with aggressive breast cancer. Ann Kaiser Stearns, 76, says her life was rocked by a long-ago divorce and a close friend’s suicide. Charly Jaffe, 29, endured a series of crises, including sexual assault, a severe sports injury, and a near-death experience when she was just a young college student.

All of these women say they are stronger today for the trials they’ve faced—and have dedicated their lives to helping others find that strength.

Ehrman, who lives in Cleveland, is a stress relief coach for first responders and people facing medical crises. Stearns, a professor at the Community College of Baltimore County, is a psychologist and author of several books, including Living Through Personal Crisis. Jaffe left a job at Google to help run a yoga school in Australia and now works as a crisis counselor, while finishing a master’s degree in psychology and education at Columbia University. She also helped her father, entrepreneur Richard Jaffe, write a book called Turning Crisis into Success.

Crisis changes all of our lives, says cognitive scientist Art Markman, a professor of psychology at the University of Texas at Austin.

“Those kinds of events create a tear in the fabric of your life story. Your life was one way before the event and another way afterward,” he says. Once a crisis recedes, Markman says, “Your job is to reweave the story of your life.” Most of us manage to do that, eventually.

But along the way, many of us make a few very human mistakes.

This Is Your Brain on Crisis

The first stage of a crisis is often an emergency—the moment you see your spouse collapse from a heart attack, smell the smoke coming from your kitchen, or hear the roar of an approaching tornado.

At such moments, Markman says, our bodies and brains prepare for action: “You breathe in a way that brings a lot of oxygen in; your heart rate goes up. Your focus of attention narrows so you can pay attention to what is going on in that situation.”

It’s the classic fight or flight response, and, when it works well, it helps us do the things we immediately need to do—calling 911 and getting an aspirin for the heart attack victim or gathering family members to escape the fire or reach the basement before the tornado hits. People in this state famously find the strength to lift heavy objects and fight off wild animals.

But people in danger also make baffling errors of judgment. They stand on the beach after a tsunami warning or run back into a burning house for a wallet. They convince themselves that their drooping face can’t possibly be a sign of stroke and take a nap instead of going to a hospital. That’s why we have drills and awareness campaigns to teach us what to do in such emergencies. Practice and a script can help us overcome denial and shock, Markman says.

That means, he says, that many of us stumble around in a state in which our thinking and emotional skills are dulled.

Missteps During Crisis

Here are some common mistakes people make while in that fog, according to the experts.

- They make big, irreversible decisions. Widows sell the family home. Angry ex-spouses burn old photos. Hurricane survivors flee their communities, leaving lifelong support systems behind. Stearns, the Baltimore psychology professor, says her rule of thumb for anyone in crisis is “don’t destroy it, don’t give it away, and don’t sell it.” Markman agrees: “Whenever possible, kick the can down the road,” and save big decisions for later.

- They isolate themselves. “Social interactions are a wonderful salve,” Markman says. Stearns says our need for social support in times of distress goes deep. “We were made to be pack animals. We are made to survive with others.”

- They confide in the wrong people. “It’s really important to avoid negative people,” Stearns says. “There are people who will judge us, people who will not keep confidences, people who will try to fix us, and some of those wrong people are our own family members, unfortunately.”

- They pretend to be fine. When Jaffe returned to college after a serious injury and life-threatening complications, she was suffering symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. “But I didn’t want to share it with anyone because I was afraid people would think I was crazy,” she says. “Instead, I would have a panic attack, wash my face, and go back to class and ask for the notes I had missed.”

- They reject professional help. “It’s not a bad thing to have someone to talk to who has some training and has no vested interest in how things come out,” Markman says. It’s especially urgent to reach out if you suffer symptoms of post-traumatic stress, such as flashbacks, nightmares, severe anxiety, or symptoms of depression, such as hopelessness, lack of interest in life, or thoughts of suicide.

- They beat themselves up. Too many people listen to a harsh inner judge at times of distress, says Ehrman, the Cleveland stress relief coach. “We tell ourselves we are stupid, we are incapable, or we never do anything right.” Many ruminate on upsetting events, looking for where they went wrong, Markman says. “They keep asking, ‘Did I miss the signs? Is there something I could have done?’”

What Happens When a Crisis Lasts?

When disaster leads to an ongoing crisis—a long hospital stay, a ruined home, the aftermath of a death—our brains and bodies often stay in stress mode. We may not have a script for what to do then.

That’s the position many people find themselves in when they become caregivers for a loved one with dementia or another serious long-lasting condition.

Stearns says too many people in that difficult situation succumb to what some social scientists call John Henryism—the affliction of the legendary steel-driving man who worked so hard at a seemingly impossible task that he died.

In her book Redefining Aging: A Caregiver’s Guide to Living Your Best Life, Stearns urges caregivers to find other role models. While we often express admiration for apparently tireless caregivers, those who never take a break risk their own health, she says.

Caregivers who find and use outside support are more likely to find meaning in their caregiving journeys, Stearns says. Those who go it alone are more likely to feel overwhelmed and spent.

Finding a Way Through

Most people are more resilient in a crisis than they think they will be, the experts say.

“Bear in mind that every life is ultimately touched by something that we consider tragedy,” Markman says. “Human psychology is fairly well designed to withstand those crises.”

While there is no single correct path to healing, “hope is looking at your situation realistically and finding a way through,” Ehrman says.

In her case, finding a way through a mastectomy and chemotherapy meant going to a therapist who taught her how to take her mind to better places—through a technique called guided imagery. Once she was healthy, she went back to school to get a master’s degree in education, with a focus on mind and body medicine. Today, she teaches guided imagery and self-hypnosis to others in distress.

Stearns also responded to crisis, a divorce at age 27, by going back to school. Seven years later, she had a doctorate degree in psychology. Later, she adopted two daughters and went on to write four books. She has faced other crises such as the suicide death of a friend and the deaths of family members, including her mother.

Losses never get easy, she says, but you do learn from them. “One of the most important things to understand from the beginning is that you have to be kind to yourself, because healing takes time, and you are going to feel bad before you feel better,” says Stearns.

Here are some things you can do to ease the pain:

- Assemble a support team. Your crisis may call for professional help—financial advisors, lawyers, physicians. But you also need people who will hold your hand and listen to you without judgment, Stearns says. Make a list of friends, family members, co-workers, neighbors, or others who might be willing to lend a hand—and then start asking them to do so.

- Accept help. It’s OK to tell eager-to-help neighbors and friends what you need—whether it’s a meal for your family, a walk for your dog, or a trim for your lawn. “We have this false belief that asking for help is a sign of weakness, but it’s a sign of strength; it’s a willingness to be vulnerable,” Jaffe says. Be prepared with a specific list of ways people can help. When someone asks what they can do, pull out your list. It might include picking up prescriptions and groceries, bringing meals, helping you with household chores, or taking shifts with your loved one so that you can get out.

- Keep up routines. If you love your job and you can work during a crisis, do it. Keep going to worship services, fitness classes, sporting events, and other places where your crisis is not on the agenda. “We all need some places where we don’t have to talk about whatever it is we are grieving,” Stearns says.

- Treat yourself. After her mother’s death, Stearns says she looked for ways to be kind to herself. She started getting regular manicures and keeping fresh flowers in her house—habits she maintains more than a decade later. When you do get time away, make it meaningful, relaxing, restorative, or fun. In other words, do not squander it on laundry, cleaning, or shopping. Instead, visit friends, see a movie, or go to a grandchild’s school play. Or find a quiet spot to read, knit, or play a favorite game with a friend.

- Tell stories. In the days after a death, people often tell the story of the loved one’s last hours over and over. When we go through any trauma—from a car crash to a nasty fall—we often feel the urge to tell that story repeatedly as well. That can be healthy, Markman says, if we are able to put together “a coherent story—something that you can pick up as a whole and put down as a whole.” Writing in a journal can help in the same way, he and other experts say.

Most of us will make it to brighter days. And it’s good to remember that, Stearns says: “There are times when we all feel powerless and weak, but in the back of your mind, you can say that ‘someday I’ll be strong.’ You just have to say that down the road, you will take this pain and do something good with it. You will find ways to learn from it.”

Here’s one of the greatest paradoxes in the science of happiness: If you survey a group of older adults about who is happier, young or old people, most will say young people are happier—but they will be wrong.

Study after study from around the globe suggests that happiness over the lifespan follows a u-shaped—or perhaps smile-shaped—curve. Both young and old people are happier than the relative sad sacks of middle age. Some recent surveys in the U.S. even suggest older adults are now happier than stressed-out young adults, says Linda George, a professor of sociology at Duke University.

At age 71 herself, George says she is “very happy.”

Of course, not everyone is happy in old age—or at any age. And aging baby boomers, as a generation, appear less happy than their parents were at the same stage, George says. But science has some more good news: There are ways to protect and increase your happiness, even when faced with the challenges common in later years—everything from illness to loneliness to loss of purpose.

“It is possible for older people to get happier,” says Sara Orem, a life coach who teaches courses in gratitude and mindfulness at Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at the University of California, Berkeley.

Orem, who left a corporate job to get a PhD at age 60, says her own efforts to find more joy have paid off. “I think I am much happier than I used to be,” she says.

The Foundations of Happiness

Before you start seeking your own bliss, it helps to know what science has discovered about happiness.

First, if you suspect that some people are naturally happier than others, you are right. Genetic factors account for up to half of the difference in happiness between individuals, according to Sonja Lyubomirsky, a professor of psychology at the University of California, Riverside, and author of two popular books—The How of Happiness and The Myths of Happiness.

“When you look around you, you see that some people are happier than others. But that doesn’t mean that we can’t be happier,” she says. “It just takes more effort for some people.” The events in our lives also matter, but they matter less than you might think.

One famous study, published in 1978, found that recent lottery winners were not significantly happier than average folks. In the same study, researchers found that people paralyzed in accidents were slightly less happy than others, but not nearly as unhappy as might have been expected.

Subsequent studies have found stronger evidence that life events do matter. Researchers have found, for example, that a welcome divorce can boost well-being, while a disabling illness can dampen it.

But hedonic adaptation—the tendency of humans to return, more or less, to a happiness set point—is always at work, Lyubomirsky says. That’s one reason, she says, that many older people can remain happy. “Most people are more resilient than they think and can adapt to even major losses,” she says.

The Secrets of Happy Aging

The common belief that older people are largely unhappy is grounded in sheer ageism, says George. “We have incredibly entrenched negative stereotypes about later life. The idea that most of us will become grumpy old men and bitter old ladies is just wrong,” she says.

“We do have our aches and pains and losses, but most of us adjust and do just fine, at least until we hit a final decline. That period of decline usually is brief and at the very end of life,” George says.

While it can be healthy for young people to worry about their futures, older people often thrive when they are able to focus on what really matters to them right now, says Alan Castel, a professor of psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and author of Better with Age: The Psychology of Successful Aging.

“Our goal is not to be happy every moment of the day, but you need to be aware that you can be happy,” Castel says. That attitude can make the difference, he says, when losses and setbacks occur.

Orem, the California life coach, says she has benefited from focusing on the good things in her life.

On a recent trip to London, she says, she and her husband realized they no longer had the stamina to walk long distances and use the subway.

“So, one day we took the bus, and it took an hour longer,” she says. When she was younger, she would have been annoyed by the inconvenience. But that day, she says, “it was so pleasant, just sitting there and enjoying the view out the window.” That kind of acceptance and appreciation, she says, can make aging a pleasure.

Ways to Get Happier

It’s never too late to pick up new habits associated with being happier. Here are a few ways to increase happiness at any age, according to psychology professor Sonja Lyubomirsky and other happiness experts.

Write a gratitude letter. Research has shown time and time again that being grateful is good for your health, mood, and general well-being. In fact, it’s one of the easiest things you can do to increase your mental health. Think about someone you appreciate and draft a letter to him or her. Through the note, tell the person how much he or she means to you, your recognition of what he or she has done for you, and how appreciative you are of his or her existence and actions. You don’t even have to send the letter to get the benefits.

Count your blessings. Happy people know how important it is to savor the taste of delicious foods, reflect on the interesting conversation they just had, or appreciate being able to step outside and take in a breath of fresh air. Happy people also tend to avoid gossip and judging others. Some people find it helpful to keep a gratitude journal, but you don’t have to write in it every day. In fact, some research suggests the sweet spot is once a week. Just take a few minutes to write down five things for which you are grateful.

Practice optimism. Think about your best possible future—the life you imagine if everything goes well over the next few years. Then spend 10 minutes writing continuously about what you imagine, using as much detail as possible. And remember, no one wakes up feeling happy every day. Even the happiest of people are no exception. Happy people just work at it harder than the rest of us. They constantly evaluate their moods and make decisions with their happiness in mind.

Practice acts of kindness. Studies suggest that performing a variety of kind acts may have more impact than performing the same kind act repeatedly. People also seem to get a boost when they pick a day of the week to perform many random acts of kindness. In fact, according to a recent Forbes article, spending money on other people makes you much happier than spending it on yourself.

Use your strengths in a new way. People with a growth mindset believe they can improve. This makes them happier and better at handling difficulties. They embrace challenges and treat them as opportunities to learn something new. Think about your character strengths—traits such as bravery, creativity, and perseverance. Then identify a new way you could use that trait today. You might use your bravery to try a new hobby or your creativity to cook a new dish. Write about your experience and how it made you feel.

Meditate on positive feelings toward yourself and others. Metta bhavana, or loving-kindness meditation, is a method of developing compassion. It comes from the Buddhist tradition, but it can be adapted and practiced by anyone, regardless of religious affiliation. Loving-kindness meditation is essentially about cultivating love. The basic idea: You sit quietly and imagine loved ones sending you love and kindness; you then send love and kindness to them.

Do more of what you like. Most people “know what makes them happy and unhappy, and they do things that make them happy,” Lyubomirsky says. “They spend time with people they like.”

A caveat: These techniques work best for people who are eager to try them. Forcing a skeptic to start a gratitude journal or a meditation practice is not going to be productive. And different techniques will work better for some people than for others.

The road of life has high points and low points for all of us. But the good news is that there are things anyone can do to lift their happiness level. So, take a suggestion that appeals to you and give it a try. The only thing you have to lose is a frown.

In this issue, we explore the latest Social Security projections and insight on planning for the future of the program, along with a look at the importance of creating and maintaining a home inventory.

Q: I’ve heard recently about financial issues Social Security is facing. Is there reason to be concerned?

A: The financial solvency of Social Security is a long-standing issue, and the media tends to sensationalize it. The latest bout of media hype started at the end of April when the trustees of Social Security released their latest financial projection. While the program’s long-term outlook has not changed much from last year, what the media didn’t tell you is that it is slightly improved from 2018 due to the health of the labor market.

According to the projection, outflows from the retirement program will exceed its income in 2020. The problem stems from people living longer, a smaller working-age population, and an increase in the number of people in retirement. By 2050, the number of Americans age 65 and older will increase from about 48 million today to more than 83 million.1 As a result, more people will be taking money out of the system, and fewer will be paying into Social Security.

What’s going to happen? First, it is important to say that this program is not going away. According to ssa.gov, among elderly Social Security beneficiaries, 48 percent of married couples and

69 percent of unmarried persons receive 50 percent or more of their income from Social Security. Congress will have to fix the program, although the fix may come with changes to contributions and benefits and may require means testing of some kind.

Considering the likelihood of changes, it’s best to make sure your retirement plan accounts for the uncertainty:

- Check your benefits. Estimate your Social Security retirement benefits based on your actual earnings record using the Retirement Estimator calculator on the Social Security website (ssa.gov). You can create different scenarios based on current law that will illustrate how different earnings amounts and retirement ages will affect your benefits.

- Stress test your plan. If you want to make sure your financial plan for retirement will work—even if Congress takes action that may lower Social Security benefits—ask your financial advisor to model multiple retirement income scenarios. For example, see what your retirement plan looks like if Social Security is reduced by 10, 20, or 30 percent.

- Take action, if necessary. If you find that you can survive with the reduced program benefits, anything you actually receive will be a boost to your income. If the analysis shows you need to consider putting aside more money to make up for a cut in benefits, work with your financial advisor to create a plan that supports those needs.

Remember that everyone’s financial circumstances are unique, so work with your financial advisor to come up with a plan that works financially for you and also gives you comfort that you’re on the right track.

Q: What is the point of a home inventory? Do I need one?

A: Many of us have made our homes in areas prone to wildfires, flooding, tornadoes, or hurricanes. But even if your home is not in such an area, you might still find yourself living through the type of disaster that makes the evening news. A home inventory is a simple way to give you and your loved ones a place to start picking up the pieces should your home experience a catastrophic event.

A home inventory is a complete and detailed written list of the property that’s located in your home and stored in other structures like garages and toolsheds. It should include your possessions and those of family members or others living in your home. A home inventory can help substantiate an insurance claim, support a police report when items are stolen, or prove a loss to the Internal Revenue Service.

In the event of a disaster, a home inventory will spare you the headache of having to create a listing of all your possessions based on memory alone.

Here are some tips to get started.

- Tour your property. Look around every room in your home and the spaces where you have items stored, such as a basement, garage, or shed. You can go low-tech and write everything down in a notebook or make a visual record of your belongings by taking videos or pictures. Be sure to open cabinets, closets, and drawers, and pay special attention to valuable and hard-to-replace items.

- Be thorough. Your inventory should be detailed. When practical, include purchase dates, estimated values, and serial and model numbers. Refer to colors, dimensions, manufacturers, and materials whenever you can. If you can locate appraisals for valuables and receipts to support big-ticket items—even better—include copies of those too. Try to identify every item that you would have to box or carry out if you were to move out of your home. Don’t forget tools and outdoor equipment like lawn furniture and barbecue grills. The only things you should leave out of your inventory are the four walls, the ceiling, the floor, and the fixtures.

- Keep it safe. You will need two copies of your home inventory: one at your home where you can easily access it and another copy somewhere else to protect it in the event your home is damaged by a flood, fire, or other disaster. This might mean giving it to a trusted friend or family member for safekeeping. If you’re tech savvy, storing it on an external storage device you can take with you or on a cloud-based service might be a good option. Regardless of whether the inventory is recorded on film, computer software, a sketch pad, or the back of an envelope, keep a copy of it stored somewhere safe, like a safe-deposit box at a bank or your desk at work.

- Update it periodically. As valuable or important items come into your possession, add them to your inventory as soon as possible. For accuracy, you should review your home inventory annually. It’s also a good idea to share an updated annual version with your insurance agent or representative to help determine whether your policy coverage and limits are still adequate.

Hopefully, you’ll never have to use your home inventory, but if you have to deal with a catastrophe, you’ll be happy you took the time to make a permanent record of all your possessions.

1 Ortman, Jennifer; Velkoff, Victoria; and Hogan, Howard, “An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States,” Census.gov, 2018.

As people begin to consider end-of-life planning, they often reflect on what type of legacy they will be leaving behind. Discussions about heirlooms and what’s going to be gifted to family members and charities often feature prominently. But what about gifting life?

Making the decision to become an organ donor is a deeply personal one—one that could provide immeasurable lifesaving benefits. Whether donating organs to those in desperate need or donating a whole body to the advancement of medical research, the donor’s gift is a way to give death meaning and to keep the memory of his or her life alive.

One Life Touches Many

Gina Kosla was 18 years old and attending Coastal Carolina College when she started experiencing shortness of breath. A cystic fibrosis sufferer, she had contracted pneumonia. Her family made a decision to fly her to Duke Medical Center in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Thankfully, Gina only had to wait six days to receive a double lung transplant. “We felt elated. In the same thought, there is someone out there who may be passing this world,” said Reyna Kosla, Gina’s mother, when describing the moment they found out an organ was available. “There is also a family and friends grieving. Whoever the donor may be at whatever time God designates this to happen, we all must think of the donor too.”

Gina’s new lungs came from Jillian Koch, a healthy 14-year-old girl, who was dreaming of moving to San Francisco to become a sculptor, when a sinus infection traveled to her brain causing a fatal subdural empyema. Deanne, her mother, describes the reason behind donating her daughter’s organs: “I needed my daughter’s life, no matter how short, to have meaning. But most of all, I wanted a part of her to live on. I simply would not accept that this was all there was, and I refused to let Jillian’s story end there. I never realized the profound impact our decision would have. It has changed my life forever.”

Jillian’s organs were also able to save a man who had been waiting two years for a left kidney and pancreas, a mother of two from New York with her right kidney, and a woman who had less than 24 hours to live with her liver. Jillian’s largest donation, her skin, will better the lives of dozens of people, such as burn victims and babies born with serious physical abnormalities.

People who decide to become organ donors can save up to 12 lives—if the hands, face, and corneas are donated—and those who choose to donate tissue can help improve the lives of up to 50 people, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The department also states that another person is added to the national transplant waiting list every 10 minutes and, as of January 2019, the total number of hopeful organ recipients was 113,000. This number is surprising since 95 percent of U.S. adults support organ donation. Unfortunately, only 58 percent of Americans are actually registered as donors.

The disparity between those who support organ donation and those who donate could be partially attributed to lack of communication. Whether donating intentions are included in a will or through a discussion with family members, it’s important to make your intentions clear ahead of time.

Those wanting to sign up as donors can go to organdonor.gov to register. If you live in a state that offers the option to become an organ donor on your driver’s license, you can always be added to the registry through the selection of the donor option.

Living Donors Gift Second Chances

Dr. Denise Laurienti is a nephrologist in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. She specializes in kidney care and the treatment of kidney diseases. She is also a kidney donor. In January of 2018, Laurienti donated one of her kidneys to her sister, Sarah Queen, who has been battling lupus since she was 7 years old.

“Ironically, I am a practicing nephrologist,” says Laurienti. “So, I see patients needing kidney transplants every day. I am frequently encouraging patients to ask family members or friends to be donors for them. I really can’t imagine how hard that would be to have to ask your loved ones. I really didn’t want my sister to ever have to ask people. I was so happy that I was a perfect match and that she didn’t have to do that.”

According to the American Kidney Fund, the average wait time for a kidney from the national deceased donor wait list is five years. Nearly 100,000 people are on the waiting list for a kidney transplant. Many more are waiting for a kidney than for all other organs combined.

A year after Laurienti’s and Queen’s surgeries, they’re both doing great. Laurienti said of her sister, “She has been skiing twice in the past year and really has had no issues. Every now and then, I have to be sure she is getting labs checked. She feels so good I think she forgot she had a kidney transplant.”

Through Laurienti’s selfless gift, she’s improved her sister’s quality of life, and now they both have the opportunity to create more memories together, as a family, for years to come.

Donating to Research Creates an Impactful Legacy

Consider how many lives could be saved if more people included whole-body donation with their end-of-life planning. Perhaps the most selfless way to leave a legacy of purpose is to donate with the aim of establishing cures and understanding.

Whole-body donation is predominately used for teaching medical students, but, in other cases, donations can help educate forensic teams on how bodies decompose, aid in the discovery of new treatments and surgical approaches, and assist in the testing of new medical devices.

These programs depend on the altruistic nature of donors to advance the medical field. According to Katrina Hernandez, vice president of donor services for Science Care, which serves as a link between donors and medical researchers, “Each donor brings a project one step closer to its goal.” Doctors and scientists wouldn’t be able to progress their understanding of diseases and discovery of treatments without whole-body donors.

Science Care is one of several organizations helping to facilitate the donating process. Each donor who goes through the organization contributes to six research projects, such as testing for earlier detection of Alzheimer’s disease, research into the latest drug therapies, and surgical training for physicians learning to perform lumpectomies and mastectomies for breast cancer.

Perhaps surprisingly, it’s easy to register to donate your body to Science Care or similar organizations. The only age restriction is that the potential donor must be 18 to join the registry. If the donor is still alive, he or she can complete a form, found online at sciencecare.com, and if the person has already passed, family members can call 800.417.3747 to register and go through a short medical screening that determines if there is a match with an ongoing research project.

Once a body has been accepted, Science Care covers all the costs, including transportation, cremation, and the filing of the death certificate.

The U.S. doesn’t have a centralized agency for whole-body donations. However, the American Association of Anatomists has come up with a policy for how bodies should be handled when they’re donated. States vary in how they accept applications for whole-body donation and where a body is gifted. In some states, such as Nebraska, donors can determine which medical institution they’d like to go to. Unlike organ donation, the age of the donor doesn’t matter, and someone can pledge to be a donor at any point during his or her life.

Whole-body donation is a socially responsible way to leave behind a substantial legacy. Not only is a donor providing a vessel to save lives, but he or she is also giving hope to future generations. Hope that doctors and scientists will discover cures for diseases such as Alzheimer’s, blindness, or even cancer. Hope that doctors will learn new surgical procedures that will help improve the future for us all.

Receiving a financial windfall should be a positive milestone that permanently alters an individual’s or family’s future for the better. Yet, gaining immediate and substantial wealth can often have the opposite effect, leading to a new set of challenges that can put that wealth at risk.

The prevalence of squandered wealth has become so commonplace that it has spawned its own financial term. Sudden wealth syndrome, a condition first identified by psychologist Stephen Goldbart in the late 1990s, describes the feelings of stress, guilt, and similar emotions associated with the gain of an often-unexpected financial windfall. Goldbart is co-founder of the Money, Meaning, and Choices Institute (MMCI), a group of psychological professionals who work with wealth holders and their financial advisors to address the emotional issues and challenges of wealth.

As MMCI explains on its website, society equates money with happiness and success. Most of us have a hard time believing that the rich have problems with their wealth. The institute has identified several primary symptoms of sudden wealth syndrome, including:

- Recurrent and persistent thoughts and impulses related to money;

- Anxiety and depression in response to stock market volatility—what they call “ticker shock”;

- Extreme guilt that inhibits good decision-making and leads to behaviors that punish individuals who believe they do not deserve their wealth;

- Confusion over identity, whether the suddenly wealthy are the same people as before and how that should affect their relationships and priorities; and

- Depression from the realization that gaining all the material things desired does not lead to happiness and satisfaction.

Other organizations have also been established to address the financial and emotional issues of sudden wealth, including the Sudden Money Institute, whose founder, Susan Bradley, created the Certified Financial Transitionist® designation.

“These struggles may result in social isolation, the breakdown of relationships, mental and physical fatigue, depression, and, in some cases, utter hopelessness,” explains CAPTRUST Financial Advisor Cathy Seeber.

MMCI views sudden wealth syndrome as a turning point in a person’s life that, if dealt with effectively, can be transformative and beneficial to not only that individual and his or her family but also to the larger community.

We have all heard about lottery winners or professional athletes who squander their fortunes, but this same sudden wealth syndrome can also impact the beneficiaries of more common financial windfalls.

A female client of Seeber’s, for example, acquired an eight-figure divorce settlement that was accelerated by the death of her former husband. The sudden wealth sparked an emotional response, causing the woman to move to Los Angeles, buy a mansion, and gift a large sum to her son to provide for his future. In just a few years, her client’s assets shrank from $13 million to $8 million.

“Wealth creates emotion, and emotion drives decision-making. Acknowledging this is a first step to coping with sudden wealth,” explains Seeber, one of a select group of Certified Financial Planners® who is also a Certified Financial Transitionist®. This is the first designation in the human dynamics of financial change and transition in the wealth management industry. Seeber’s training enables her to address the feelings and values triggered by sudden wealth in addition to the traditional financial consequences.

How wealth is acquired can often determine the best strategies for managing it. An inheritance or life insurance settlement from the unexpected death of a family member comes with its own emotional and financial issues, while the unsolicited sale of a business may also leave a business owner unprepared to deal with his or her new reality. Other wealth transfers are more predictable, such as a large sale of stock, a company going public, or the passing of a loved one with a terminal condition.

“You want to help people figure out how they will adapt to change when the windfall occurs, and you want to do this ahead of time whenever possible,’’ says Seeber, who works with clients across the country. “All these decisions impact a person’s well-being.”

“The root cause of a client’s lack of implementation of sound advice is his or her inability to adapt to change. Anticipation of a life-changing event, experiencing the actual event, and integrating the event into your life can involve a tremendous amount of internal realization. When the work isn’t addressed because no one notices it’s there, negative consequences occur,” says Seeber.

From a tactical standpoint, Seeber advises sudden wealth recipients to resist the urge to act rashly. Instead, she suggests putting newly gained assets in a safe place—such as a money market account or certificate of deposit—allowing adequate time to prioritize their situations and form a plan.

Angat Saini, an attorney with Accord Law in Toronto, also recommends depositing most newly acquired assets in an insured account, but says allowing for a small spending spree can be a helpful part of the transition process. “Take some of that money and spend it right away—in order to satisfy the urge to impulse spend,” Saini says. “That way you can get that urge out of your system while a long-term financial plan is being created.”

Dealing with such urges and emotions are so ingrained in a person’s psyche that Seeber and other financial planners often recommend assembling a planning team that includes not only a financial advisor, estate planning attorney, and accountant, but also a therapist.

Such expertise can help individuals not only cope with their sudden wealth but plan prudently for the life changes that wealth will bring.

“Sudden wealth syndrome is really not a syndrome because it’s not a group of signs and symptoms,” Seeber says. “Most recipients don’t see it coming, although there are some who go through the anticipation of sudden wealth.”

Seeber educates clients on the four stages of financial transition associated with a financial windfall:

- Anticipation. Prepare for an event that has not yet occurred.

- Ending. Some aspect of life has come to an end, and perhaps your identity has changed as a result.

- Passage. It takes time to relate to the change and adapt to it.

- New normal. Establish the beginning of a new life after the event has been fully integrated.

Not every instance of sudden wealth comes with an anticipation stage, but they all involve a passage from an individual’s or family’s former life to a life with significantly more financial assets. The passage stage can last years. “Some people try to force passage, but this is an important learning stage, where you can dream and set expectations and build the brain trust of your financial plan,” Seeber says.

During the passage, individuals’ feelings can run the gamut from the power of possibility to fear, anxiety, chaos, and even survivor guilt. Many sudden wealth recipients fear their identity will be compromised, while others become mentally and physically fatigued from dealing with all the new issues that wealth creates.

Some recipients of sudden wealth worked diligently their entire lives to realize a liquidity event such as the sale of a business. Such individuals may immediately consider the tax and wealth transfer implications or the need to invest their proceeds. This can be of concern to older wealth recipients who may plan to pass on their windfall to heirs. Saini suggests establishing trusts as an effective way to distribute wealth—both gifting assets during the recipient’s lifetime and reducing estate taxes upon death.

A complete understanding of the purpose of the new money and the outcome the individual would like to create is also crucial. An exercise in managing the expectations of others is equally as important. “Most people jump right to the financials, but if they don’t understand the why of their wealth, then the what doesn’t matter,” Seeber explains.

Instead, she recommends asking three important questions when facing a life transition: What do you need to protect? What do you need to let go of? What “new” needs are going to be created now, soon, and later?

This third question can set the stage for assembling the brain trust that will help form a comprehensive financial plan. As Seeber likes to say, “Good decisions make a

good life.”

It’s a common estate planning worry. Would a large inheritance squelch your children’s drive to carve their own paths in life? Billionaire Warren Buffett of Berkshire Hathaway has been suggesting for decades that you should leave your children enough money so they feel they can do anything, but not enough so they’ll do nothing.

It’s a conundrum many parents and grandparents will have to face in the coming decades. Over the next 25 years, a staggering $68.4 trillion in wealth is expected to transfer between generations, according to a 2018 report from research firm Cerulli Associates.

Are the heirs prepared to handle all that money? There’s a lot to worry about. A nest egg intended to cushion kids’ lives could instead lead to failure to launch. Kids could spend their way through hard-earned fortunes in a few years. Too much comfort could sap their natural ambition. Also, they might be treated differently by people because of their money or fall victim to gold diggers and false friends.

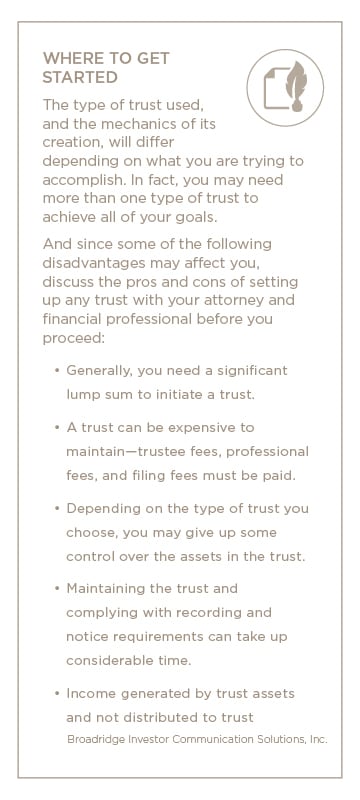

The best solution? Estate planners say a well-designed trust can provide families with plenty of protection against inheritance loss or inadvertently creating a stereotypical trust fund baby.

Influencing Heirs from the Great Beyond

Estate planning attorney Tyler Britton says he’s noticed an interesting difference in the way baby boomers are now using trusts for the upcoming generation of millennial heirs. “As an estate planner, I am seeing an increase in the amount of conditions found in trust documents,” says Britton, professor of trust and wealth management at the Lundy-Fetterman School of Business at Campbell University in Buies Creek, North Carolina.

The individuals creating the trusts want to set up guardrails that take into account the beneficiaries’ different lifestyles, priorities, and desires. These conditions allow a grantor to feel like he or she is still in control during his or her lifetime or after death. Perhaps it’s no surprise that the cohort that invented helicopter parenting would try various avenues to micromanage their survivors’ financial paths—even after they depart this life.

A trust is basically a legal agreement in which one party—called the grantor or trustmaker—puts assets (like real estate, cash, stocks, or bonds) in the care of another party, the trustee. The trustee manages the assets and carries out the instructions over time, for the benefit of a third party, the beneficiary, who could be a person or an institution.

Doesn’t a last will and testament take care of all that? Only partially.

A will gives instructions for distributing your property and is essential for naming guardians for minor children. But you typically can’t set specific conditions in a will, such as requiring your daughter to finish medical school in order to inherit your house. With a trust, you could make such a condition—or virtually any condition—giving you greater control over the distributions that are made.

The Flexibility of Revocable Living Trusts

There are many types of trusts, but the most common is a revocable living trust. It’s called “living” simply because it goes into effect while you’re alive, and “revocable” in that you are free to change the instructions you provide.

“A trust allows a grantor to specify conditions for receipt of benefits, such as income or principal. Furthermore, a trust allows a grantor to spread trust income or principal over a period of time, instead of making a single, lump sum gift,” says Britton.

For example, you can set age-based payouts. “Twenty or 30 years ago, it was common for a grantor to specify that his or her heir could not access trust principal until the heir attained the age of 21 or 25,” says Britton. “With millennial heirs, some grantors are opting to set the age to receive trust principal to 30, 35, or even 40. Their reasoning varies from apprehensions about millennial spending, saving, and work ethic to concerns about creating trust fund babies.”

A trust can be set up for a specific number of years or for the child’s lifetime, for example. The trustee could manage the principal and use investment income to pay distributions to the child. A drawn-out payment schedule, such as a distribution every five years, can prevent the inheritance from being spent too quickly.

“Other common conditions include postsecondary education requirements and drug testing,” says Britton.

Irrevocable Living Trusts Provide Liability Protection

Irrevocable living trusts can’t be terminated and are very difficult to change. Such trusts can be used to reduce taxes or protect assets against creditors or lawsuits.

“A common use for an irrevocable trust is to provide asset protection for a grantor and his or her family. By placing assets into an irrevocable trust and naming an independent trustee, a grantor relinquishes control over and loses access to trust assets. Therefore, if structured properly, the assets in an irrevocable trust cannot be reached by a grantor’s creditors,” says Britton.

That doesn’t mean you can escape existing legitimate debts just by moving all your money into an irrevocable trust.

“If a grantor conveys assets to an irrevocable trust in order to defraud or delay a legitimate creditor, a grantor is engaging in fraudulent conveyance. If a creditor can prove fraudulent conveyance, a court can reverse a grantor’s asset transfer to a trust and allow creditors to access trust property to satisfy judgments,” cautions Britton.

Spendthrift Trusts Protect Heirs from Themselves and Others

A spendthrift trust won’t turn your heirs into financial whizzes, but it can safeguard property in the trust from loss. “The term ‘spendthrift’ is often misleading. Not only does this type of trust protect heirs who lack proper judgment when it comes to spending money; this trust also protects financially responsible heirs from certain lawsuits and creditors,” says Britton.

While money is in the trust, your heir can’t spend it, give it away, or lose it. “In other words, a beneficiary cannot spend or pledge his or her interest in a trust, and certain creditors cannot seize a beneficiary’s interest in the hands of a trustee,” says Britton. Once it’s paid out from the trust, however, the beneficiary can spend the money in any way he or she sees fit, and it would no longer be protected from creditors.

Special Needs Trusts Protect Eligibility for Benefits

Another reason for an irrevocable trust would be to provide financial support for a child with a disability, while protecting his or her eligibility for public assistance. You can put money or property into a special needs trust and appoint a trustee to use the funds to purchase necessities for the beneficiary. The beneficiary doesn’t own the property in the trust, so it would not prevent the person from applying for government benefits.

Trusts are traditionally associated with the very wealthy, but even middle-class families can take advantage of trusts to clarify how assets should be distributed after death. An estate planning professional can help you design a trust that best fits your particular situation.

The next time your stomach is growling as you dash from one office building to the next, you might want to watch your step. There’s a new kind of street food craze sweeping the country, and its ingredients could be right under your feet.

Urban foraging is an inside-the-city-limits version of the ancient practice of searching for and utilizing edible wild plants. And while it might seem surprising to think that a big-city environment could provide a between-conference-calls snack—much less the ingredients for a full meal—urban foraging has become wildly popular.

Chefs are taking to the streets to add foraged greens to their dishes. Parks and nature preserves are offering guided wild edibles tours. And while many cities are beginning to regulate urban foraging in public spaces due to its growing popularity—more on that later—municipal areas still offer savvy foragers an opportunity to spice up their daily meals with highly nutritious wild foods.

“Trying to survive on wild plants would be a serious challenge, but a diet made up of 10 percent wild foraged foods is as easy as can be,” says Mark Vorderbruggen, a Texas-based research chemist and edible wild plants expert who teaches urban foraging techniques at the Houston Arboretum and other Lone Star nature preserves. “And many of these plants are literally growing up around the sidewalk, so it’s mainly a matter of opening your eyes to what’s right there under your feet.”

Consider the redbud, a small flowering tree that grows on city streets across the country. It’s one of the earliest flowering trees, with stunning red-purple flowers that cling directly to the tree’s branches. Even if you don’t know the plant by name, it’s a good bet you’d recognize a redbud once it was pointed out.

And redbud is a prime urban foraging plant, says Vorderbruggen. In the spring, those striking flowers that turn the heads of passersby are delicious when plucked from the tree and eaten raw. They can be added to salads or used to top cupcakes and pies. And a few weeks after blooming, each of those flowers turns into a peapod. “Just like something you’d see in the grocery store,” Vorderbruggen says. “When they’re about a half-inch long, they are tender and delicious, and you can eat them raw or add them to a stir-fry dish.”

All from a common landscaping tree.

It’s the same with plants such as purslane and lambs- quarter, wild onion, and peppergrass. Urban environments around the country are chock-full of edible wild plants, from lesser known fruits such as persimmon to a virtual salad bar of greens that grow from sidewalk cracks to front yards to greenways. In the South, wax leaf myrtle is an oregano-like plant that adds a definite dash to lasagna. The tender leaves of common plantain have a nutty, close-to-asparagus taste and can be quickly stir-fried in olive oil. The young shoots of Japanese knotweed—a hated invader across much of the country—have a lemony, rhubarb-ish taste that’s led them to the kitchens of Manhattan chefs.

In fact, many of what we consider weeds in North America are actually beloved garden plants brought over by European settlers that now grow wild. Sow thistle and dandelion, Vorderbruggen says, were cultivated as food plants. But since they don’t have pests and predator controls in the American environment, they’ve spread so quickly and far that we now consider them weeds.

And while toxic plants abound—making plant identification a critical foraging skill—these wild foods can be very healthy. Foraging experts point out that the plants tend to be denser with nutrients than many of their cultivated counterparts, thanks to growing in soils that haven’t been depleted over decades of farming.

Collectors need to be aware of areas that have been sprayed with herbicides or pesticides, and stay away from older buildings with lead paint that can leach into soils. But many wild plants have dense root systems that tap minerals deep in the soil and transfer that bounty to delicious leaves, shoots, and flowers.

Every Rose Has Its Thorns

The growing interest in wild edibles has some cities working to make sure foragers don’t love a local park’s hedgerows to death. Cities such as Chicago and Washington, D.C., have outlawed foraging on public lands such as street rights-of-way and municipal parks.

It’s not allowed in New York City, although guerrilla foragers are common in Central Park. So, it’s always suggested to check local foraging laws wherever you are. And where foraging on public lands is allowed, be sure to stay away from sensitive habitats, such as wetlands, and take no more than you can use in a single meal.

And the best approach, says Vorderbruggen, is an even more hyper-local strategy. “Start in your own yard and in your own neighborhood,” he says. “Begin at your doorstep and identify the plants you see every day, and you will be amazed at what’s edible.” Then move out from your own yard to your neighbors’ yards.

When you walk the dog or ride a bike, figure out what plants look interesting, and you’ll likely see a few that can find a place on your plate.

“This is so much easier than pulling out an identification guide and looking for a particular plant,” Vorderbruggen says. And you sidestep any regulations on plant collecting when you forage on lands nearby. “Just ask a neighbor, ‘Hey, do you mind if I weed your lawn?’” Vorderbruggen laughs. “And then tell them what you find. People just can’t believe all the food that’s right there in the front yard.”

We have all heard the Chinese proverb: Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime. What if plan sponsors thought of retirement planning for their employees along the same lines?