Over the past year, women have individually and collectively spoken out against gender inequality and decided that the cost associated with staying quiet is too high. Celebrities like Ashley Judd, Reese Witherspoon, and Oprah Winfrey declared “Time’s Up” when it comes to the sexual and financial mistreatment of women in Hollywood. This movement has sparked a dialogue that extends beyond the entertainment industry and into all our homes.

This cultural phenomenon presents a great opportunity for women and men to break the money silence and discuss taboo topics like money and power. At times like these, dialogue may cause discomfort, but there has never been a better time to engage in these conversations.

Why now? Because the economic strength of women is on the rise and power dynamics at home and at work are changing. According to the Center for Talent Innovation, the number of wealthy women in the U.S. is growing twice as fast as the number of wealthy men. Currently, women oversee $11.2 trillion in investable assets. By 2030, they will control two thirds of the nation’s wealth.

Despite these positive trends, many women are still paid less than men. The average woman earns 81 cents to every man’s dollar, and the gap widens if you are a woman of color. This pay inequality puts many women and their families at a financial disadvantage. Whether they are primary breadwinners, co-contributors to their families’ incomes, or stay-at-home moms, this type of discrimination impacts them and often renders women silent.

The gender wage gap surfaced very publicly when Michelle Williams, an A-list actress, was paid $1,800 for reshooting scenes in the movie All the Money in the World. Her male costar, Mark Wahlberg, received $1.5 million for the same work. The difference? Wahlberg used his voice and demanded his contractual reshoot fee, whereas Williams accepted the standard fee without question. In the end, Wahlberg donated his salary to the Time’s Up legal defense fund and showed that men are an important part of the solution.

If even the rich and famous cannot overcome this issue, how likely is it that women can advocate for themselves? This challenge may sound difficult, especially if negotiating your salary is a new skill, but it’s possible.

Consider the following women’s stories…

McKenzie, a 25-year-old paralegal, spoke up when she was promoted to a new position with more responsibility. Unfortunately, when she asked the human resource director for a salary increase, she was called greedy. “The worst part is the human resource director is a woman,” McKenzie said. She did receive a pay increase, but only because she was persistent, professional, and determined not to let gender bias stop her.

But what if you don’t work outside the home or contribute only part of the household income? Do you still need to talk more about money and advocate for yourself ? The short answer is yes.

Danita is married with an adult daughter. She feels strongly that women have to have an equal stake in their financial health and well-being. “I remember when my father-in-law had a stroke and couldn’t manage the daily tasks as he once did. My mother-in-law was lost, never having paid a bill or written a check in her life. I remember thinking, ‘I never want to be in that position, and I never want to see my daughter in that position either.’”

Danita and her husband believe that managing money is an important life skill. They have made a commitment to raise a financially literate daughter and serve as role models for how couples can talk openly and honestly about money and share financial decision making.

Gina also believes that women need to take part in money management. As she says:

When a woman speaks up about finances and participates in money conversations, that leaves an impact of being equal—regardless of her role, whether she’s a stay-at-home mom or someone who works part time—in all decisions. It enables her sons to have respect for women and be inclusive in conversations with them—rather than feeling like financial discussions are the purview of men only—and for daughters to be raised as strong, independent women.

Different life-changing experiences spurred these women to make a change. But you don’t have to wait for a promotion or a loved one’s illness to act.

Here are a few tips on how to be an advocate for breaking money silence about women and wealth right now.

Take an Active Role in Your Financial Life

Don’t delegate your financial decision making to someone else. Instead, participate in identifying your short-term and long-term financial goals and working toward achieving these objectives. If you are a member of a couple, attend legal, tax, and financial advisor meetings with your partner. If you are single, find trusted advisors to work with. Ask questions. Learn as much as you can about how to be financially fit today—and financially secure tomorrow.

Be a Role Model

Set a good example for the next generation. Show your daughters, sons, nieces, and neph-ews how women can play an active role in their financial lives. Set a powerful example by managing your money and discussing the impact of your gender on your finances. If you are a man, use your role as a husband, father, uncle, or brother to show your loved ones that no matter a person’s gender it is important for them to be a part of household decision making and planning.

Get Involved

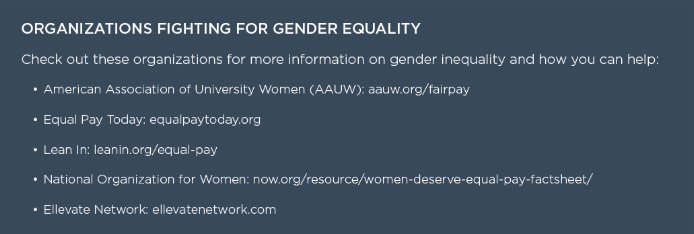

There are many opportunities to support the fight for gender pay equality. Get involved with organizations that advocate for gender parity. Contact your local senator and congressional representatives and encourage them to support legislation to end financial discrimination. Run for political office or support a qualified female candidate. Or volunteer to teach financial literacy to young girls. Whatever you choose to do, you will make an impact. The Time’s Up movement shows the power women can have by speaking up. Yet, silence persists around taboo topics like money and power. With women’s economic strength rising and dynamics at work and home changing, the time has never been better for women and men to break this money silence.

Moving homes at any age can be stressful. The organizational and physical tasks can be immense, and for older adults, this process can easily become overwhelming. Understanding the challenges seniors and their families will face while either transitioning to a new residence or making the necessary updates to a current home are why people are looking to senior move managers for assistance.

Before Anne Nieland became a senior move manager in Urbandale, Iowa, she was teaching art classes to senior citizens. That’s where she fell in love with their demographic. She often heard her students talking about how they needed help moving and always volunteered to lend a hand. Nieland found this work to be incredibly rewarding. Eventually, her husband suggested she turn it into a business.

“I didn’t realize there was an actual industry. I went to conferences, got a mentor, and job shadowed,” Nieland says.

Now, Nieland finds herself constantly busy with her thriving company, Smart Senior Transitions. She says, “I am willing to do anything and everything for my clients,” which can range from finding a trusted real estate agent within her treasure trove of contacts to the arduous job of setting up televisions.

A large portion of her time is spent going through what can be decades of clutter. She asks her clients, “Do you use it?” and “Can you part with it?” If they’re willing to let it go, it ends up in the van, where Nieland’s favorite saying comes into play, “The van makes things vanish.”

For unwanted items, Nieland says, “I try to keep as much out of the landfill as possible.” She can find value in just about anything. She goes on to say that ripped or stained sheets are always needed at animal shelters, partially used cleaning products can go to a women’s center, used glasses can be donated to a Rotary Club, and just about every client has a drawer full of discarded cables that can be dropped off at any Best Buy. If a client wants to try selling instead of donating, Nieland selects the best-suited consignment shop for that item.

It’s inevitable that clients’ emotions get brought to the surface while sifting through meaningful items. When Nieland was packing up a recently divorced client, they came across personal correspondence from her ex-husband. The client, understandably, got very upset. Nieland often faces clients who get angry, frustrated, and teary. She’s learned how to pay attention to triggers and knows when to ease off.

Nieland says, “We’re ripping open old wounds. It’s a lot of listening and paying attention to how they’re feeling. Sometimes you sit on the couch and let them cry. It’s hard not to cry myself. The ride home is often in silence. No radio. No calls. Just deep breaths.”

According to Nieland, it’s challenging not to form personal relationships in this line of work. “It’s virtually impossible not to become friends. They’re so warm and appreciative,” she says. She often hears from her clients long after a job has been completed. After hours of working together, they’ve developed a relationship, and clients will call to check on how she’s doing.

What Exactly Does a Senior Move Manager Do?

Senior move managers are experts who specialize in resettling older adults and preparing them for a different lifestyle as they age. Essentially, they’re project managers with extensive practical knowledge about the costs, available local resources, and obstacles that can arise when downsizing. While specific services vary, most senior move managers offer the following:

- House cleaning

- Waste removal

- Shopping

- Assistance with Realtor selection

- Helping to prepare a home to be sold

- Packing and unpacking

- Scheduling movers

- Donating or selling furniture

- Sending special keepsakes to family members

- Calling the cable company and other utilities

- Preparing a new home with safety features

But Nieland often finds herself going off-menu. She describes having an 88-year-old client who is in excellent health and has no intention of moving; instead, the client enlisted Nieland’s help for after she passes. When that day comes, Nieland knows where everything needs to go and, most importantly, will be the one to oversee the welfare of George, the client’s beloved dog. In addition to providing comfort and peace of mind, Nieland is helping this client’s family by relieving them of the burden and heartache of packing up their loved one’s belongings.

Some families are geographically hindered and can’t help their loved one pack and move. Senior move managers can be useful in this type of situation. They can figure out the best and most cost-effective way to ship items to family members and friends and, perhaps most importantly, they can be there as a comfort to help with the emotional element of relocating.

Talking Through Senior Living Options

Nieland assists her clients in determining whether they want to live independently in their current or new home or in an assisted senior living community. Often, older adults and their families are unaware of many of the costs associated with staying at home, while others might not know about all the options available for assisted living. However, Nieland never gets into the specifics of health care or offers financial advice regarding the cost benefits of options.

When an older adult decides to age in place, a senior move manager can help turn their home into a safer dwelling. Nieland recommends modifications such as, “getting them to cook with an induction stove [which uses magnetic fields and turns off when a pot or pan is removed], widening doorways, adding ramps, and raising items such as the washer and dryer.”

A Network of Senior Move Managers

The National Association for Senior Move Managers (NASMM) is an excellent resource and networking tool. For example, Nieland had a client who was relocating to a different state. She was able to use the NASMM to find a trusted senior move manager operating in the client’s destination state. This person assisted with the unpacking and setup of the client’s new home. Both senior move managers worked as a team to accomplish the goals of the client.

In another instance, Nieland found herself having to crate and ship a rather large art piece. So, she turned to the community and asked, “I have a life-size statue of a horse, what do I do?” She ended up receiving some helpful tips, and the horse made it to its new home in one piece. When asked if having the responsibility of shipping treasured items makes her nervous, she replies, “It’s like running a road race: you’ve prepared and you’re confident in your resources, but you still have butterflies.” Jokingly, she adds, “Also, I have liability insurance.

”Since this is an industry based on the needs of older adults, who can at times be vulnerable, it is important for the NASMM and all their members to follow a strict code of ethics. There is usually a free in-home evaluation, followed by a written estimate of the time and cost of a job, before any payment is processed. Some senior move managers charge on an hourly basis, while others prefer to package everything together at one price.

Being sensitive to this demographic, Nieland tailors each service, as well as her hourly rate, to every client’s specific need. She advises clients not to sign the contract the same day, and she encourages them to talk to their families before doing so.

While uprooting oneself from a well-lived-in home of many decades can be stressful and intimidating, it is a comfort to know there are caring people, like Nieland, willing to help with the transition.

Serial entrepreneur Cindy Eckert sold her last company for $1 billion, got it back for next to nothing, is launching a controversial drug that could be the next blockbuster, and is on a mission to make other women equally rich. Never underestimate @cindypinkceo.

A Pharma Career Wasn’t the Plan

At least not at first. As a graduating business major, Cindy Eckert was hell-bent to work for Merck Pharmaceuticals, not because of the industry but because it perennially ranked as a Fortune MagazineWorld’s Most Admired Company. “I wanted to work for the best business out there, and I figured I could take that and apply it anywhere,” Eckert said.

She ended up falling in love with the science and how it could change people’s lives. She stayed in pharma, stepping to ever smaller companies to be closer to research and development and be heard. In 2007, she started her own company, Slate Pharmaceuticals, which redefined long-acting testosterone treatment for men.

Then she heard about flibanserin, a daily pill that treats low libido in women. Boehringer Ingelheim, the pharmaceutical giant that developed the drug in the 1990s, had given up on it after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration rejected it by unanimous vote.

Eckert contrasted the FDA’s ready acceptance of treatments for men while dismissing options for women. She sold Slate, acquired flibanserin (branding it Addyi), launched Sprout Pharmaceuticals—and kickstarted an improbable David-and-Goliath crusade.

A Tale of Two Genders

The path to FDA approval was a journey marked by gender disparity. For example, while Viagra had been fast-tracked for approval in only six months, Addyi was again rejected by the FDA, even though Eckert had three times as much data. “I had done the work I needed to do, and then I got rejected. That was not a good weekend.”

This is the point where most drug makers go away. But Eckert received a moving letter from a woman who had been in the clinical trial. Her marriage and self-esteem were suffering, all the result of a brain chemistry imbalance outside her control. She implored Eckert to continue the fight.

“For women like her to be denied a treatment option was heartbreaking and infuriating,” Eckert said. “So, on Monday I showed up in the office and told everybody we were going to dispute the FDA.”

It was an audacious move for a tiny company, one so small that all the staff could fit into an elevator, Eckert quips. Could the female chief executive of a newly born startup take on the FDA with any prayer of succeeding in a third attempt at approval?

Yes. In 2015, the FDA finally approved Addyi. Two days later, Eckert sold Sprout for $1 billion to Valeant Pharmaceuticals and looked forward to seeing Addyi launched worldwide. That was not to be; under its new ownership, Addyi was shelved.

So, Eckert and a group of Sprout’s shareholders sued Valeant on the grounds that it overpriced the pill and made little effort to commercialize it. Valeant, which not much earlier had made Eckert a very wealthy woman, handed Sprout and Addyi back in exchange for dropping the suit. Valeant also extended a $25 million loan to restart the business, asking only for a small cut of royalties from future sales.

For the second time, Eckert had won control of the drug without having to write a check.

“Women with a medical condition deserve access to a medical treatment, not our value judgments on whether or not they need it or the worthiness of treatment,” said Eckert. “The science had spoken, and we needed to listen. I wasn’t in this to create the next blockbuster drug. I was in it to make sure women have access and get to choose for themselves.”

Advocating for the Unexpected

After getting a $1 billion payday from the sale of Sprout to Valeant, some of Eckert’s friends were disappointed she didn’t retire to relax on the beach with pink cocktails. You know, live the billionaire dream.

But her struggles to bring Addyi to market—being routinely underestimated along the way—left her impassioned about women’s lack of access to mentoring and money in business. “I shouldn’t be in a club that’s lonely,” Eckert said. “I shouldn’t be in a club in which so few other women have gotten to exits like mine. I need to get other women there, and I need to get them there faster than I got there myself.”

She knew what it felt like to always be unexpected in the room, to navigate a sea of gray suits as a female in stilettos and hot pink. To see worthy ideas sidelined because of preconceived notions. She had seen all that and made it. She also acknowledged how much help she had received along the way from powerful women—policy leaders and those who bravely spoke to a federal agency about an intensely personal subject.

“I’d had a front-row lesson in what it means for women to advocate for themselves and each other,” said Eckert. “So, my next act was going to be about advocating for an earlier version of me, the young woman entrepreneur who can’t raise money because the system doesn’t give her a chance. Consider that 2 percent of venture capital is given to women. You cannot tell me that 50 percent of the population has 2 percent of the good ideas.”

She resolved to champion for all of the unexpecteds in the room, those who didn’t come from Silicon Valley or didn’t attend the business school with the crowd that had inside access to capital.

So, in 2016, The Pink Ceiling was born.

The Pink Ceiling is a venture capital firm, “pinkubator,” and consultancy with a mission to support women-centric biotech startups that could drive real social change.

“We put our creativity, contacts, and cash to work for cutting-edge concepts and founders,” said Eckert. “The thesis is: Let’s stack the billion-dollar club by smashing the pink ceiling together.” She’s on a mission to make women rich.

It isn’t about the money for the sake of it. It’s about bright, passionate women having access to operational support and capital, so they can bring forward the next generation of advances in health tech. Money provides the freedom to make decisions, invest in what matters to them, and pay it forward again.

Only Groundbreaking Business—by or for Women—Need Apply

Eckert looks for companies that offer a patented breakthrough in health tech, will catalyze some important social conversation, and are unequivocally by and for women.

The ideal founder also has a certain DNA that makes her scrappy. Eckert likes those who are self-made and overlooked by the system at large because they are young, female, or not connected into privileged networks. The first round of partners includes 10 innovators:

- Undercover Colors produces a wearable decal that detects common date rape drugs.

- Fathom produces a wearable biometric sensor that collects and interprets movement data to improve athletic performance and prevent injuries.

- uMETHOD combines big data analytics and medical research to improve outcomes for those with Alzheimer’s disease.

- Seal Innovation’s SwimSafe wearable technology helps prevent drowning, the leading cause of accidental death in children.

- Pursuit Sleep Technology (aka Senzzz) embeds sleep center science into wearable consumer products to reduce snoring and improve sleep quality.

-

Lia Diagnostics has created the first FDA-approved, flushable pregnancy test.

-

IntuiTap developed the world’s first imaging device to guide a needle for spinal taps, epidurals, and steroid injections.

-

Medolac is the only company that provides shelf-stable human milk products for babies in need.

-

Renovia created a non-surgical device that addresses incontinence for women by training pelvic floor muscles.

-

Sunscreenr makes a handheld device that reveals vulnerabilities in sunscreen coverage.

The relationship with these companies is not just an investment play. “We’re very selective,” said Eckert. “We’re not playing the odds and saying, ‘we’re going to make x many investments; we figure 8 out of 10 of those are going to fail, but we’re going to have two big wins.’ We’re really picking a company to sit alongside. Almost all of them are between a year and three years out from launch, and we’re going to help them get there.”

Partner companies—often led by scientists and engineers rather than business experts—have access to The Pink Ceiling space, resources, and a business team that knows how to build companies. “So much of this is walking back through my own past and what I wish had gone differently,” said Eckert. “Do I wish somebody had told me their experience? Like, ‘I’ve stepped on that land mine, step left. I’ve done that; don’t do it. You don’t need to repeat it.’”

By making early bets on these companies, The Pink Ceiling also builds their credibility. “We raise money through our fund, but you want to bring in other partners with diversity of thought and strategic sense,” Eckert notes. “It helps validate these companies that somebody has already said yes.”

Changing Perceptions

As an engineering student at Purdue University, Jessica Traver knew she would be one of very few girls in her classes. “I never really noticed or had an opinion on gender bias until I founded IntuiTap and started pitching to physicians, investors, or pretty much anybody. It was just so obvious then that people weren’t taking me as seriously.”

“People say, ‘I never would have expected that you’re an engineer or a company founder. You just don’t look like one.’ And 90 percent of people didn’t get that what they just said is wrong,” said Traver.

Traver is 20-something, five-foot-ten with long blonde waves. “When she walks into the room of a conventional venture capital firm and sits at a board table, she’s already discounted,” said Eckert—too model-like to possibly be an engineer who designed a revolutionary medical device.

IntuiTap’s “stud finder for the spine,” as Eckert humorously describes it, replaces manual palpation and guesswork with a device that uses a heat map to find the right spot and advance the needle by itself. “When Jessica’s company is bought by one of the giants, she will change everybody’s perceptions when the next five-foot-ten blonde engineer in her 20s walks into the room.”

Or consider Bethany Edwards, co-founder of Lia Diagnostics, makers of the world’s first flushable pregnancy test. “Bethany is about four-foot-nothing, little glasses, full of power, and she’s come to really change the world,” said Eckert. “She has masterfully patented a groundbreaking first that will be an interesting conversation starter in women’s health. And I love the idea that it will surprise everybody that it’s Bethany at the helm of this.”

Edwards shares the unifying principle of The Pink Ceiling—women helping women in a big way. “Not only is Cindy investing in women and really encouraging them to lead their companies, but she’s also trying to make sure they have successful exits, so they can, in turn, reinvest in other women. Her candor in wanting to help women get rich is pretty important, because that is one of the only ways you can move the needle on power structure.”

An Opportunity to Pay it Forward

“I hate squandering opportunity,” said Eckert. “Today, I have an opportunity I never imagined, to get onto a big stage in front of all of these young women who are rising stars and help them. The privilege is all mine, that they’ll wait and ask me questions, and I think, you’re further ahead than I was at that same age. So, you’ve got me beat and then some.”

“It’s just such an honor to get to do that. We’re doing that in a small way, but we’re loud about it. We’re loud about it so that others will do the same—and so those who come in and get to be part of it also feel their obligation to pay it forward as well.”

A Decidedly Pink Office

The Raleigh, North Carolina, office of The Pink Ceiling is strikingly pink. Not “it’s a girl” pink. Not cotton candy pink. Not a gentle blush. It’s a fierce, hot pink, and so are Eckert’s suits. “I wear pink all the time. You should see my closet.” It’s a declaration about the dismissive way people talked about Addyi as “the little pink pill.”

“You can run away from gender stereotypes, but if you’re me, you run right toward it,” Eckert said. “The idea that there isn’t something valuable and unique that a woman brings to the table and in owning her femininity—pink for me is about owning it as a woman, unapologetically pink. I like pink. I’m going to wear it. I started showing up in blazing pink to the FDA and said, ‘We are going to have this conversation.’”

A new generation of companies that provide goods and services on demand via smartphone applications has begun to reshape consumer and worker behavior, providing both groups with more choices than ever before. The growth of these services has created a gig economy, where workers are independent freelancers who choose their own hours and assignments over permanent employment.

Although most people, an estimated 89 percent, are not familiar with the term gig economy, the majority, more than 70 percent, have participated in it by using a shared or on-demand online service.1 When planning a vacation, you can rent a beachfront condominium directly from a homeowner rather than stay at a resort. Instead of renting a car, you can request a ride with your phone and popular ride-sharing apps such as Uber or Lyft. What if you need someone to pet sit while you’re away, or you want to come home to a detailed car or a completed landscaping project? Today, there’s an app for just about anything. New gigs can emerge quickly in this technology-fueled environment. In the city of Raleigh, North Carolina, over the course of a single summer weekend, flocks of electric, pay-by-the-minute Bird scooters appeared, with riders soon zipping along sidewalks, leaving some less cheerful drivers and pedestrians wondering what had just happened and city officials scrambling to catch up with regulation. What isn’t as visible is the troop of paid Bird hunters who drive around town after hours to collect, recharge, and reposition the scooters, in a type of scavenger hunt meets part-time job.

The growth of the gig economy presents opportunities and challenges to all market participants. It has been described both as the Industrial Revolution of our age, with the potential for massive gains in productivity—and as the end of job security. It’s been hailed as a liberator for workers seeking to work on their own terms and criticized as a predatory system that leaves workers underpaid, overstressed, and more unprepared for the future than ever before.

What’s the real story? Is it a good gig?

What’s the Gig?

Services or service platforms that make up the gig economy share a few common traits, such as:

- The ability for consumers to grant (or gain) temporary access to underutilized assets, such as a vacation home or a car, with idle capacity. Cars, for example, are unused for 95 percent of their lifetime.2

-

Greater flexibility for both buyers and sellers of goods and services. Consumers and businesses gain the ability to buy services or contract help on demand, and sellers or providers of services can choose when to work, including nontraditional hours that fit with their lifestyles or other time commitments.

-

A willingness by both sides to conduct business with strangers. In a decentralized model, building mechanisms for trust becomes one of the primary roles of the platform provider, whether that’s a driver or riders given ratings in a ride-sharing app or your eBay feedback rating.

Gigs Past

The comparison to the Industrial Revolution is interesting, because in some ways the gig economy seems like a 180-degree turn. As economic historian Louis Hyman describes it, the Industrial Revolution of the 18th century saw a movement of workers from farms and artisans’ shops to centralized locations where their efforts could be coordinated and managed. They earned a wage instead of the profits of their labor. This change in labor patterns, when accelerated by the new technology of the day—steam power and assembly lines—powered massive gains in productivity.

Today, the movement is in the reverse—from formal, centralized workplaces to more flexible, loosely affiliated work arrangements. This phenomenon is not new. Hyman explains that it has been underway since the 1970s: “Over these four decades, we have seen an increase in the use of day laborers, office temps, management consultants, contract assemblers, and every other kind of worker filing an IRS form 1099.

”More recently, what has changed is the pairing of workers’ appetite for short-term, independent employment with smartphone technology platforms to connect these workers to buyers. As with the Industrial Revolution, technology did not create the movement; rather, it has accelerated it. Digital gig platforms, for example, solve the challenges of efficiently linking buyers and sellers, establishing trust, setting a price, and facilitating payments.

Gigs Present

The Brookings Institute has estimated that this facet of the economy will grow from $14 billion in 2014 to $335 billion in 2025.3 However, the size and growth rate of the gig economy labor force is not easily captured in official employment statistics. In 2016, the JPMorgan Chase Institute estimated that around 1 percent of adults had earned income in a given month from online platforms, and that more than 4 percent had participated over a three-year period.4

In addition to replacing a traditional full-time job, gig economy workers may also use the platforms to earn extra income. Business strategy consulting firm McKinsey & Company, with a somewhat broader set of criteria for independent workers, put the number at 20 to 30 percent of the working age population. They also found that these workers participate in the gig economy for primary or secondary sources of income and either out of choice or necessity.5 Figure One breaks down the numbers.

Gigs Future

The gig economy is likely to affect aspects of our lives and economy that are difficult to imagine today. Studies have shown that where ride-sharing services are widely available, many choose to use them in lieu of ambulances for emergency room visits. From farm equipment and private aircraft to personal and professional services and skilled trades, the gig economy stands to alter the ways in which many services we rely on will be provided, with implications for all stakeholders.

Consumers

The driving forces behind the growth in gig economy services are convenience, flexibility, and price. By matching providers and consumers directly, in many cases using physical or human assets that would otherwise be idle, these services can remove layers of costs. Beyond choice and price, consumers also stand to benefit from greater service availability, particularly in areas underserved by traditional businesses. But a variety of risks—beyond the risk of an inexperienced driver behind the wheel—also face consumers in this new business environment where innovation has so far outpaced regulation. One such risk is the potential for new forms of discrimination. A 2017 Harvard Business School study found that guest acceptance at a leading home-sharing service was 16 percent lower for users with names that did not sound distinctly “white.”6 Future regulation is likely to focus on limiting the impact of potential discrimination on online platforms, both from the humans and algorithms involved in decision making.

Workers

The balance of costs and benefits to workers is perhaps the most hotly debated aspect of the gig economy. The fundamental tradeoff to workers is one of flexibility versus security. The ability to clock in and clock out with a swipe of a smartphone screen empowers workers to create a work-life balance that meets their own unique circumstances, limitations, and obligations.

As the Pew Research Center’s work on the gig economy shows (Figure Two), not surprisingly, alternate employment is most popular among younger and lower-income workers. The gig economy seemingly combines the more nomadic work preference of millennials with the always-connected-to-your-phone behavior of Generation Z.

Another group likely to benefit from the gig economy are skilled workers that have been marginalized by the rigid requirements of traditional full-time work. As professor and author Diane Mulcahy explains, “Stay-at-home parents, retired people, the elderly, students, and people with disabilities now have more options to work as much as they want, and when, where, and how they want, in order to generate income, develop skills, or pursue a passion.”

On the other side of the ledger are the costs and risks to workers. There is no free lunch, and the flexibility benefits of gig employment must come at a cost. Examples include:

- Greater income volatility and potentially lower incomes for the same types of work;

- Fewer workplace safety protections;

-

Lack of valuable benefits packages typically provided by employers, including paid vacation and sick leave, health insurance, and retirement programs; and

- Tax complexity.

Taken together, these costs cause a dollar of gig earnings to be worth less than a dollar from traditional employment. Gig-oriented work can also take a toll on health, with studies suggesting that a decade of irregular work could lead to a cognitive decline of 6.5 years (compared to those working regular hours).7

Businesses

As with most shifts in technology or consumer taste, the gig economy represents both opportunities and threats to traditional businesses. With unemployment at record lows and businesses of all types struggling to find qualified workers, the prospect of scaling the workforce on demand—and potentially without the overhead of benefit and employment costs—may be appealing in fields where skills are more commoditized and transferrable

At the same time, employers may face a new source of competition for their already scarce talent pool. Against this new form of competition for workers, the gig economy may prompt employers to extend similar types of flexibility to their own workers. And against new gig economy competitors, businesses will not just compete for workers—they will also compete for customers.

As always, there will be winners and losers, and the companies that thrive will be the ones most attuned to the shifting preferences of their customers. Of course, these preferences—and the challenges of how to fulfill them—are changing at a heightened pace, thanks to technology trends.

The Economy

A fundamental premise of the gig economy is that suppliers and consumers of goods and services can be matched directly and efficiently through technology. This has the potential to improve capital efficiency and productivity. But once again, these gains do not come without costs and risks.

How does the gig economy affect the American dream of a tidy house with two cars in the driveway? If consumers can easily rent homes, cars, boats, planes, recreational vehicles, and snowmobiles on demand, then the same asset base is able to meet the demands of a larger population of consumers, with perhaps a disinflationary impact to the economy.

Finally, a thorough look at the gig economy must consider public benefits and security programs, such as Social Security, unemploy-ment, and health and retirement systems. In an extension of the trend from employer-provided retirement security through traditional pension plans toward defined contribution plans like 401(k)s that share the responsibility for retirement savings between employers and workers, workers in a gig economy will bear even more of the responsibility for financial security and retirement savings.

A Gig in Transition

In my travels across the country for client meetings over the past few weeks, I’ve made it a point to ask ride-sharing service drivers about their experiences in the gig economy and their motivations. I’ve heard from drivers who are making ends meet while they:

- Take real estate and community college classes,

- Interview for jobs after college,

- Study for the bar exam after law school, and

- Save to start a new organic produce business.

In each of these cases, the gig job is not a long-term objective. Rather, it’s a means to an end. If the availability of flexible, short-term work arrangements allows these individuals to start more businesses, retrain themselves, and acquire the skills required in our changing economy, it may be a small gig that leads to a much bigger stage. Only time will tell.

1Smith, Aaron, Shared, Collaborative and on Demand: The New Digital Economy, 2016.

2Yaraghi, Niam and Ravi, Shamika, The Current and Future State of the Sharing Economy, 2016.

3Ibid.

4Farrell, Diana and Greig, Fiona, Paychecks, Paydays, and the Online Platform Economy, 2016.

5Manyika, James, Lund, Susan, Bughin, Jacques, Robinson, Kelsey, Mischke, Jan, and Mahajan, Deepa, “Independent work: Choice, necessity, and the gig economy,” 2016.

6Edelman, Benjamin, Luca, Michael, and Svirsky, Dan, “Racial Discrimination in the Sharing Economy: Evidence from a Field Experiment,” 2016.

7Marquié, Jean-Claude, Tucker, Philip, Folkard, Simon, Gentil, Catherine, Ansiau, David, “Chronic effects of shift work on cognition: findings from the VISAT longitudinal study,” 2014.

We are now more than a decade into the era of the Pension Protection Act of 2006 (PPA), which ushered in a range of new ways to encourage retirement savings in defined contribution plans, including automatic enrollment, automatic escalation, and qualified default investment alternatives (QDIAs). This is a long enough period to begin drawing some conclusions about the utilization, success, and shortcomings of new and existing tools for participants. At CAPTRUST, our experience working with more than 2,000 defined contribution plans provides insights into plan sponsor challenges and successes that we can learn from and share. Synthesizing these insights has led to a set of best practices that help plan sponsors optimize the effectiveness of their defined contribution plan.

Impact on the Employer

A successful retirement savings program has the potential to improve participant outcomes, but also impact company performance. Employees who are confident about their retirement savings are likely to be more productive and have better attendance than those who are concerned about their finances. These employees are also less likely to have to delay retirement due to inadequate savings, which can help employers with workforce management.

Lowering the need for employees to keep working beyond their targeted retirement age can also avoid the negative financial impact on the company of assuming higher healthcare and benefits packages for older workers. A study by Prudential showed an incremental cost of over $50,000 for an individual who delays retirement by one year and an estimated incremental cost of between 1 and 1.5 percent across an entire workforce. Prudential also found that more than 50 percent of employers believe a significant portion of their workforce will have to delay retirement due to inadequate saving.

These risks should give plan sponsors ample motivation to do what is necessary to turn retirement savings from a potential liability into an asset.

What constitutes an optimized defined contribution plan will vary by employer and will often be based on employee demographics and needs. To make the most of their defined contribution plans, plan sponsors should focus on four key elements:

- getting employees into the plan;

- getting them to save an adequate amount of money toward their retirement goals;

- getting them invested appropriately based upon their specific circumstances; and

- getting plan participants engaged in the saving, investing, and, ultimately, retirement planning process.

Many tools are available to improve outcomes in these areas. This article focuses on helping plan sponsors best utilize these tools and monitor success across these four key elements.

What Is Success and How Do You Measure It?

To optimize their defined contribution plans, plan sponsors need to promote the success of plan participants. The four key elements of plan optimization—what we call the “road map”—are a helpful guide in assessing employee success and can be measured by:

- Participation rates—How much of your workforce is in the plan?

- Deferral rates—Are participants deferring enough of their compensation?

- Diversification—To what extent are participants utilizing diversified investment options such as target date funds, risk-based funds, managed accounts, or models?

- Engagement—Are participants engaged, as measured by their usage of websites, call centers, and in-person employee events and meetings?

The Road Map

1. Getting Employees into the Plan

Of course, employees cannot use the plan to save for retirement unless they are enrolled and setting aside a portion of their earnings. The more traditional multichannel approach to driving plan participation through print communications, web tools, and (possibly) in-person meetings got plan sponsors only so far. Since the effective date of the PPA, however, these traditional tactics have been overshadowed by employers adding an automatic enrollment feature, which has proven to be a key driver of increased participation; plans with automatic enrollment consistently show higher participation rates than those without this feature.

For all industries, the average retirement plan participation rate has risen 18 percent in the past decade, primarily due to the rising popularity of automatic enrollment. As Figure One illustrates, the growth and the use of automatic enrollment features is on an upward trend.

Figure One: Growth of Automatic Enrollment (2006-2016)

Source: 60th Annual Survey of Profit Sharing and 401(k) Plans; Vanguard “How America Saves 2017”

2. Getting Employees to Save Enough

Once participants are enrolled in the plan, the focus shifts to adequacy of savings, commonly termed retirement readiness. Plan sponsors can help participants gauge if they’re on track for retirement with readiness tools. These tools forecast retirement income and savings adequacy by calculating the total amount of assets needed in retirement or by showing the percentage of monthly income that a participant is on track to replace in retirement.

The first step to saving enough is maximizing the percentage of pre-tax compensation an employee contributes to his or her plan, known as deferral rate. Once again, automatic features have proven to be key catalysts in improving outcomes, starting with higher default percentages for automatic enrollment. Three percent has been the most common starting percentage, but we are now seeing a shift toward higher default rates. In fact, more than 40 percent of CAPTRUST plan clients offering automatic enrollment now start at a default rate of 4 percent or higher. Further, adoption of automatic escalation, where a participant’s deferral rate increases annually—typically by 1 percent each year—can lead to substantially higher deferral rates over time.

We see a direct correlation between plan size and plan designs that include automatic features. Companies with more than 5,000 employees are much more likely to offer them than smaller firms, as shown in Figure Two. One thing we have observed is that innovations that take root with larger plans often work their way into smaller plans, so we may see higher adoption of automatic features among smaller plans over time.

Figure Two: Adoption of Automatic Features by Plan Size

Source: CAPTRUST 2017 Plan Design Benchmark

3. Getting Employees Invested Appropriately

Once enrollment and deferrals are in place, the next step to retirement readiness is ensuring participants are appropriately invested. Most plan sponsors accomplish this by adding diversified asset allocation funds that serve as the plan’s QDIA. Participants who do not make an investment election are defaulted to the plans QDIA. Among the investment options and solutions eligible for QDIA protection, target date funds are the most popular—with 89 percent of our defined contribution plan clients utilizing them.

Target date funds, along with other types of professionally managed options, benefit employees by reducing the likelihood of holding extreme or undiversified allocations. According to Vanguard’s “How America Saves” study, 0 percent of participants in a professionally managed investment option held either a 0 percent or 100 percent equity exposure. In comparison, 20 percent of investors not in a target date fund or similarly managed investment option held one of these extreme allocations. Target date funds provide meaningful benefits by promoting diversification and automatically lowering the risk of retirement portfolios over time.

Managed accounts are also gaining traction in defined contribution plans. While few plans use managed accounts as their QDIA, we see this changing as they gain further acceptance. Managed accounts consider a participant’s age when designing an asset allocation but can be further customized based on factors such as salary, deferral rate, account balance, and marital status. And because managed accounts are more customized to the individual, studies have shown increased participant engagement. According to Morningstar, investors who use a managed account service increase their deferral rates by an average of 2.19 percent.

Regardless of the type of professional help utilized by a plan—whether the plan uses target date funds or managed accounts—the benefits of offering help to plan participants can be meaningful. A multiyear study found that participants receiving professional help, which included those using target date funds, advice services, or managed accounts, had median annual returns more than 3 percent higher than those who did not receive help.

4. Getting Employees Engaged

The final optimization step is getting participants engaged. The first element of an integrated engagement program is print communications. To resonate with participants, print materials should be personalized and targeted to a specific audience. One method is to create content specific to each separate generation of participants. These groups have different views of retirement and are facing very different decisions based upon their life stages. Communications also need to be action oriented—for example, challenging participants to take advantage of their employers’ matching contributions.

Call centers are another important component in engagement that can deliver anything from fund information to tailored investment advice to participants, depending on the services engaged. When this service is utilized, it’s important that plan sponsors have the capability to monitor call activity—both why their participants are calling and what is being recommended to specific groups of employees on outbound calls.

Plan websites are another way to engage participants, and better technology has improved the effectiveness of these websites over the years. Sites now offer customized retirement readiness tools, personalized messages, monthly retirement income projections, and recommended next steps that participants can easily execute.

While technology provides convenience, personal meetings are a very effective way to drive individual engagement. Participants still generally feel most comfortable talking to an expert about retirement planning, and the ability to give employees one-on-one advice is a significant driver of long-term success. This advice should take a holistic approach that considers a participant’s complete financial picture rather than just retirement assets.

Each channel of engagement can impact employees to varying degrees, and plan sponsors should strive to measure each method to determine effectiveness and make necessary changes.

What Are the Roadblocks to Success?

The many behavioral biases that confound investors in general also have an impact on retirement investing. Individuals are inherently biased in ways that can interfere with their ability to adequately save for retirement. Status quo bias—or investor inertia—describes the tendency for employees to prefer their current state and delay decisions that they know are in their best interest. One such decision is starting to save for retirement as early as possible. Decisions that require action now, such as enrolling in a retirement plan or choosing the right investments, are often delayed.

To combat inertia, many plan sponsors have added automatic enrollment to their plan designs. Initiating that first step for participants and getting them into the plan makes it unlikely that they will opt out. In fact, the average participation rate of plans with automatic enrollment is about 87 percent—compared to 50 percent for plans without it.

Another major challenge to address is present bias, the tendency to place a greater value on the current benefits versus future benefits. Most employees would prefer to receive a higher paycheck now over accumulating more for their retirement later. To overcome present bias, plan sponsors have added automatic escalation features. Combining automatic escalation with automatic enrollment increases the likelihood of participants saving enough. Placing participants in diversified investment portfolios that serve as QDIAs can further neutralize inertia by automating the asset allocation and de-risking of portfolios over time.

Plan sponsors must also navigate several other roadblocks. These include the degree of financial literacy among plan participants, the financial cost of implementing programs that drive success, and addressing the needs of varying demographics within their employee base. Most defined contribution plans serve multiple generations of participants, all with different financial needs and communication preferences.

What’s Next?

Advancements in technology have been a huge driver in what’s next in helping plan sponsors engage their participant base and improve retirement readiness. Examples of these advancements include gamification, improved mobile access, and aggregation tools.

Gamification is the application of elements of game playing to areas meant to improve engagement. In the case of defined contribution, an employee could get points for achieving certain goals or passing different life stages. The higher the score, the more prepared they are for retirement. Benchmarking a participant against those in their own peer group has also proven effective.

More access to retirement accounts through mobile devices is also gaining traction among plan participants, particularly younger employees. Participants want access to their retirement accounts through mobile devices, along with the ability to transact and get help; technology among recordkeepers is quickly catching up to meet this demand.

Finally, account aggregation tools are a way for participants to be holistic and consider all their retirement assets, not just those accrued with their current employer, when making investment decisions. Account aggregation tools allow plan participants to add outside accounts when calculating retirement readiness or when making allocation decisions among investments. If managed accounts are utilized, the investment manager, with the help of the participants, can use an aggregation tool to consider these outside accounts when making investment decisions.

The Destination

The optimal defined contribution plan will be unique to the circumstances of each plan sponsor, yet each should focus on a few key priorities: getting employees into the plan, getting them saving enough, getting them invested appropriately, and getting them engaged in the process. To help support retirement readiness, plan sponsors should keep participants engaged and active throughout the savings process.

Plan sponsors can stack the odds of success in the favor of participants by implementing plan design features such as automatic enrollment and automatic escalation and combining them with qualified default investment options such as target date funds or managed accounts. These features can be enhanced with advice or financial wellness programs and targeted communications. All these things, along with technology enhancements, are moving the dial forward on participant retirement readiness, making it easier for plan sponsors to help participants reach their destinations.

Once the kids have flown the nest, or a family business has matured and changed hands, you might decide that a life insurance policy purchased years ago is no longer needed. As life circumstances change, the coverage may not seem worth the premiums.

Your first thought might be to surrender the policy back to the insurance company in exchange for whatever cash value it has. But if you do, you could be unwittingly leaving money on the table. A less well-known option—life settlement—could yield you a better price or a better financial outcome for your family.

With a life settlement, a company purchases your policy as an investment, taking over the premium payments and receiving the rights to the death benefit. “Say you had a $1 million policy that was meant to protect the children. You’ve reached retirement age and no longer need it, but are still paying premiums,” says Mike Molewski, a principal and financial advisor at CAPTRUST Financial Advisors in Allentown, Pennsylvania. A policy with a cash surrender value of, say, $100,000, could potentially be sold to a life settlement company for several times that amount.

But you have to know what to ask. Normally, “insurance companies will send you the surrender form and cash the policy in. They do not advise you that you can sell the policy,” says Molewski, who provides life insurance strategies and wealth planning services to high-net- worth individuals and families.

That means it’s up to policyholders or the financial advisors acting on their behalf to do the legwork in order to unlock any hidden value. A life settlement could yield a lump sum to defray the cost of long-term care, pay for a couple’s travel plans, help with a grandchild’s tuition—or any purpose at all.

Who Should Consider a Life Settlement?

Life settlements are suitable for people age 65 or older who have a permanent, cash-value life insurance policy and a life expectancy longer than two years. Term life policies are, in some cases, eligible for life settlements if they are convertible to a permanent policy.

If you’re 65 or older and considering dropping or reducing life insurance coverage, investigate the benefits of a life settlement before surrendering a policy, says Molewski, especially if there have been any changes to your health status since you purchased the policy.

From a financial standpoint, it’s not always obvious what’s best. It’s only by methodically working through the math, often with the guidance of a financial advisor, that the policyholder can navigate to the best decision, he says.

A life settlement differs from a viatical settlement, which is the sale of a life insurance policy by a person with a critical illness, typically with a life expectancy of two years or less.

Case Study: Large Policies, Unaffordable Premiums

Molewski helped an 82-year-old client navigate a life settlement for the $10 million universal life no-lapse guarantee policies she purchased 17 years earlier. Her husband had passed away, and the premiums—about $450,000 a year—had become a burden. Although she had paid several million dollars in premiums over the years, the surrender value of the policies was just $225,000. Molewski helped her shop the policies to licensed life settlement companies and received multiple offers. “If there are a number of policies, we try to sell the weaker policies and keep the stronger ones,” he says.

He advised her to sell a portion of the policies to raise enough money to pay off the premiums on the rest of the coverage. She didn’t receive cash in the sale. Instead, the proceeds were applied toward future premiums payments, so she was able to keep $3.6 million of coverage in place without having to pay any more premiums. This type of life settlement is called a retained death benefit supplement. Her family had no additional cash outlay and will eventually receive a tax-free life insurance payout 16 times greater than the present-day cash surrender value.

Side Benefit: Assess Your Unneeded Policy as an Investment

People who buy life insurance as protection for their families sometimes have trouble assessing their policies as investments—the same way they would a stock or bond. That’s why it’s useful to have your unneeded policy evaluated for a life settlement, even if you ultimately choose not to do one, says Brodie Barnes, a principal and financial advisor at CAPTRUST in Salt Lake City. Barnes is known as one of Utah’s top life insurance specialists and works primarily with ultra-high-net-worth clients and businesses.

The life settlement shopping process provides insight into how professional investors see your policy. “What I love about the life settlement marketplace is that it often helps my clients or their families decide to keep their life insurance policies and understand them for the great investments they are,” says Barnes. He says, when people receive high life settlement offers on their unneeded policies, they often start to feel it’s more worthwhile to keep paying those premiums.

Case Study: Attractive Offer, But No Thanks

One of Barnes’s clients is an 85-year-old woman with a $1.5 million policy that she purchased years earlier to provide funds for estate tax payment. When the federal estate tax exemption increased, she no longer needed the coverage. She and her family considered surrendering the policy for the cash value of approximately $45,000. But Barnes said, “Let’s look at this. There is potentially more value in a life settlement than in the surrender value.”

Based on health records, it was determined that the policyholder had a statistical life expectancy of four years. (Note: For planning purposes, it’s important to recognize that, by definition, a person could live for a shorter or longer period than the mathematical average life expectancy.) A life settlement company made an attractive life settlement offer of $700,000. After tax, the family would have had a net gain of $640,000, about 14 times the surrender value.

Even so, Barnes encouraged them to hold on to the policy. He calculated that even if they continued premium payments for six more years (two years past life expectancy), they could expect a return on investment of a bit over 10 percent a year once they ultimately received the tax-free death benefit. That high rate of return would be hard to beat with any other investment. Since the family could comfortably afford the annual premiums of $44,000 a year and had no urgent need for money, they decided to keep the policy.

In today’s market, Barnes says life settlement companies aim for a 12 to 14 percent return on capital—meaning their outlay for the life settlement and the premiums they expect to pay.

“What family doesn’t want that same kind of return?” says Barnes. He says it’s often more advantageous to hold on to your life insurance policy than sell it, unless the premiums become unaffordable. The family may decide it’s smarter to keep a policy as an investment once they hear how much an investor is willing to pay for it.

File #0576-2018

So much energy and passion come out of listening to live music that it’s hard to imagine how it could get any better than that. But add traveling to your favorite city or a city you’ve always wanted to visit, and you get a music vacation.

Ever wonder what it would be like to see your favorite artist in an iconic setting, like the Beacon Theatre in New York City? Or maybe listen to a show under a starlit night at the acoustically sublime Red Rocks Amphitheater? Or maybe travel to the birthplace of jazz to attend the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival for an authentic immersion of music and culture? This practice of music tourism is becoming a popular trend among baby boomers. More financially secure, they’re now able to enjoy live music and travel as a whole new experience.

Marcela Curry heard rock and roll for the first time when she moved to the U.S. from Chile when she was 15 years old. She remembers thinking, “Wow, what’s going on here?” and has been hooked on rock and roll ever since. Curry loves the history behind rock music—how it’s derived from the blues and the way some lyrics can seem like the workingman’s poetry.

Marcela and her husband, John, treat themselves to vacations around locales where the likes of U2, Bruce Springsteen, and the Foo Fighters have upcoming shows. They’ll pick a city they want to visit and then see who’s playing at the local venues.

Curry once went to multiple Tom Petty shows in one tour. Every show had the same set list and the same Tom Petty banter, but it was the last show in Boston that she felt was by far the best. According to Curry, this was due to the warmth and harmony of the crowd reacting to the music. Plus, there was the bonus of visiting Boston, one of her favorite cities.

Live music has a way of bringing people together and enhancing emotions. Hearing your favorite artist live can make you feel connected to the performer and the community around you.

A specific song can become significant to someone because they can relate to the meaning behind the lyrics.

A study conducted by digital communications company O2 and Patrick Fagan, an expert in behavioral science, revealed that experiencing just 20 minutes of live music resulted in an increase in feelings of well-being by 21 percent. Feelings of self-worth and closeness to others both went up 25 percent, and mental stimulation climbed up 75 percent.

The researchers claim that all these increases, experienced twice a month, could result in an additional nine years added to a person’s lifespan.

Mike Gray, a financial advisor at CAPTRUST, has always enjoyed taking in a live show. He especially loves the thrill of the find—when he discovers a new artist, seemingly obscure to the general public, to add to his playlist. Gray has transferred his love of music to his son, Roth, and daughter, Addison, both now in their 20s. He admits, “I’ve ruined the kids with classic rock.” His daughter lamented to him once that the Talking Heads follow her everywhere she goes.

Gray often takes his grown children on trips to exciting cities. The next show on their itinerary is to see As the Crow Flies, a new incarnation of The Black Crowes, in Lexington, Kentucky. Taking music mini-vacations is a way for Gray to continue to bond with his kids and perhaps retain an element of cool in their eyes.

For some, gone are the days of pinching pennies for concert tickets, waiting in long entry lines, and getting an elbow to the face while dancing in the pit. Those who grew up with the Grateful Dead and the rise of music festivals, such as Woodstock, are now older and potentially more financially stable, so they can look for new ways of enjoying live music.

And there is a whole world of VIP and platinum packages to pick from. Companies such as CID Entertainment offer fans of live music an array of services, including hotel packages, luxury bus rentals to and from the event, artist meet and greets, VIP viewing access, pre-show gatherings, and cocktail parties. Anything you can think of to aid in a hassle-free and premium experience is now available.

Then there’s the whole revamped festival experience. While there’s still the option of general admission camping—where you bring your own tent and brace yourself for a weekend of roughing it—organizers are now offering options to provide fans varying levels of accommodation, concert viewing, and hospitality services.

Those who have a passion for live music are happy to offer up their time and money to be part of its universe. John Martin, another financial advisor at CAPTRUST with this passion, said, “I don’t like music, I love it, and I spend a fool’s amount of money on it.”

Martin often jumps on a plane to see a show in New York City or Nashville to feed his live music addiction. And a couple years ago, he took a trip to Arrington, Virginia to attend the Lockn’ Festival. He and a couple friends decided to enhance their festival experience by renting an RV and purchasing VIP tickets. Their VIP package offered clean, air-conditioned bathrooms with showers and access to the VIP viewing area with complimentary food and non-alcoholic beverages.

For this year’s Lockn’ Festival, to be held in August, concertgoers can go even further by renting a “glamping” tent. This package includes a queen bed, complete with memory foam mattress—a far cry from a sleeping bag on the hard and unforgiving ground—table and chairs, mini-fridge, daily personal shopping service, bath products and towels, tent lighting, and a fan to keep cool. It sounds a lot like staying in a hotel, but having access to a VIP Glamping Lounge where there will be yard games, comfy furniture, snacks, coffee, and breakfast takes it to a new level.

Whether you’re a diehard U2 fan ready to travel near and far, or you love visiting Nashville and wandering into smaller venues to hear local bands, music travel is a way for people to take in new sights, have an adventure, and feel part of the live music community.

Margareta Magnusson gets right to the point: “Let me make your loved ones’ memories of you nice—instead of awful.” That’s how the Swedish artist turned author opens her recent book, The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning: How to Free Yourself and Your Family from a Lifetime of Clutter.

Yes, this is another book about the joys of de-cluttering—or The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up (the title of another such book, by the Japanese organizational maven, Marie Kondo).

But Magnusson, who reports that she is “somewhere between 80 and 100 years old,” has something more in mind. She is asking her fellow elders not just to pare down their excess possessions, but to face the truth: you are not going to live forever, and, when you die, someone else will have to clean up any remaining mess—and make decisions about every earring, painting, sweater, kitchen pan, and file folder you leave behind. If there are love letters in your attic, someone is going to find them. If there’s a broken garden gnome in your garage, someone else is going to have to figure out what to do with it.

“I have death cleaned so many times for others, I’ll be damned if someone else has to death clean after me,” Magnusson declares.

“But, cheer up,” she says, “a good death cleaning, or döstädning, as the Swedes say, does not have to be grim.”

Instead, she writes, it can be an invigorating opportunity to prepare for a new phase of life and to share memories with family members as they stop by to help (and, if you’re lucky, take a few things off your hands).

Our Overstuffed Lives

“If you can’t keep track of your things, you know you have too many,” Magnusson writes.

That would seem to describe a lot of Americans. In fact, when researchers asked a nationally representative group of more than 1,100 people over age 60 whether they had fewer things than they needed, more things than they needed, or the right amount, 60 percent said they had too much, says David Ekerdt, a professor of sociology and gerontology at the University of Kansas. At age 85 and beyond, more than half said they still had too many things.

“People are well aware that they have more than they need,” he says.

Just how much stuff do we have? Researchers who have attempted to answer that question have found the task overwhelming, Ekerdt says. In one case, a research team set out to count the objects in 32 American family homes. They counted 2,269 items in two bedrooms and a living room of the first house alone. While they were ultimately unable to account for every object, they did come up with some household averages for certain categories. They found, for example, an average of 438 books and magazines, 212 music CDs, 39 pairs of shoes, and an astonishing 52 objects affixed to the sides of refrigerators.

Ekerdt’s own research has looked at how hard people work to rid themselves of excess possessions as they age. One key finding: people in their 60s and 70s are less likely than people in their 50s to clean out, give away, donate, or sell household items. People in their 80s and beyond are even less likely to do anything to lighten their material loads. It’s possible, Ekerdt says, that people have finished all their cleaning before they reach their later years, but the fact that so many elders feel they still have too much argues against that interpretation.

Decluttering professionals say there’s no doubt that aging Americans are sitting on huge piles of unloved possessions.

“It’s a growing problem,” says Mary Kay Buysse, executive director of the National Association of Senior Move Managers. The group represents more than 1,000 small businesses that help seniors pare down their possessions so that they can move or—increasingly—age in place more comfortably.

The problem stems in part from the housing and borrowing booms of the past few decades, Buysse says. “The American dream was to get a house in the suburbs and fill it to the max.”

And while families do tend to get rid of some things as they pass through life’s stages—shedding the baby gear, the children’s toys, the outgrown clothes, and the outdated electronics of their former selves—at some point, stuff tends to pile up in attics, garages, and basements, in junk drawers, and in jam-packed kitchen cabinets.

And when it all gets to be literally too much? Many people throw up their hands and rent a storage unit, Buysee says, putting off the hard decisions indefinitely.

Why Death Cleaning Is Hard to Do

We have more than we need. And we know we can’t take it with us. What’s stopping us from paring down?

The sheer size of the job is daunting, of course. It requires physical and mental stamina, and declining health is one reason people may never get around to a good downsizing or death cleaning, Ekerdt says.

“There really is a point called ‘too late,’” he says.

Emotional readiness also can be a big factor. “We accumulate things because we have these roles in life. We are parents; we are householders, we have things that help us do our work,” Ekerdt says. “Giving up those things can be a stumbling block. If I give away the roasting pan, am I still the mother?”

Saying goodbye to objects that represent deep values—even if the objects themselves have little value—“can require a grieving process,” says Rosellina Ferraro, an associate professor of marketing at the University of Maryland.

Even things we have never used can hold emotional power, says Julie Morgenstern, an organization and time management consultant and author of Shed Your Stuff, Change Your Life. The cookbooks you never cracked open, despite your vows to eat better; the fashionable dress you never wore because the right party never came along; the still-shiny tool set; the abandoned sewing machine.

“Letting go of those things means accepting giving up on those goals,” Morgenstern says.

If you really are not ready to do that, then now is the time to “read those books, cook those meals, do those sewing patterns, and, by gosh, enjoy them,” Ekerdt says.

But if you are ready to let go of some things, you may face other obstacles. The biggest may be learning that no one else wants your old stuff. That includes your grown children. Today’s young adults are not very interested in mahogany furniture and fine china, Buysse says. “They have a more minimalist mindset,” she says. “They can go to Target and outfit a whole kitchen for $200.”

And with so many retirees now trying to downsize at once, even charities have become pickier, Buysse says. People who attempt to sell things online and at yard sales, auctions, and consignment shops often are disappointed as well, she says. “A lot of people are just crushed by the fact that their stuff is not worth anything.”

But once people accept those realities and get down to work, most can find a way forward, Buysse says.

“It can be an uplifting journey,” she adds. “It does not have to be about loss. It can be about the future.”

How to Get Started

“Before you touch anything, you want to get into your head a motivation,” Morgenstern says. “What are you making space for?” For one client, she says, the motivation for clearing out a “magnificent” four-bedroom Manhattan apartment was not just a move to a smaller place, but the time and freedom that would give her to play music and volunteer at her old music school.

Then, the experts agree, it’s time to do your research. Tell your children, grandchildren, and others what you are planning, and ask them to start thinking about what they would like to have. Find out which charities will take which things and whether there is any market for your artwork, silver, or fine furnishings—keeping your expectations for profit low.

Then Get Some Boxes and Trash Bags and…

Whatever you do, do not start with the photographs, Magnusson advises. They stir up too many emotions and take a lot of time to process, she says. (When you do get to the photos, be prepared for your children to insist on digital copies, Buysse says, and to pay someone to do the scanning and downloading for you, if that task seems overwhelming.)

The experts agree that it’s best to start with things that mean the least to you. “Start in a room or a part of your house that does not have much of an emotional attachment,” Buysse says. “Have your plan of attack so that you end up in the most emotional place.”

For some people, that may be a deceased spouse’s closet; for others it might be a garage workshop or maybe a kitchen.

Morgenstern’s advice is only slightly different: she suggests moving by category—books, clothes, furniture, whatever—and starting with the largest volume of items that you care about the least. That will give you the momentum to keep going, she says.

“If you go object by object, you will never get through it,” she says.

The beauty of death cleaning is that it will come to an end when you die, Magnusson writes. Until then, she says, opportunities should keep presenting themselves. What if you are invited for lunch? “Don’t buy the host flowers or a new present; give her one of your things.”

Of course, not everything is for sharing. Magnusson suggests that we do our descendants a favor by putting together a box of items—maybe some of those love letters or other souvenirs—that have meaning only for us. Write “throw away” on the outside of the box. If you feel less sentimental, good for you, she says. Gather up those potentially embarrassing letters, documents, or diaries and “make a bonfire or shove them into the hungry shredder.”

And remember, the experts say, your survivors may not feel all that sentimental if you leave them with a mess. They may never separate the treasure from the trash. Buysse warns, “Many families just call for a dumpster, and the kids start hauling things out in black Hefty bags.”

Don’t Skip Your Finances

They need death cleaning too.

When was the last time you updated your will? How about your funeral plan (you do have one, right)? And does anyone besides you know the passwords for all of your banking and investment accounts—or even how many banking and investment accounts you have?

If those questions make you break out in a sweat, it may be time for some “financial death cleaning”—an effort to put your affairs in order and help them make sense to others if you should die or become incapacitated tomorrow.

“We all want to think we are going to live forever or never become incapacitated,” but we can leave a financial mess behind if we do not prepare for the inevitable, says Carolyn Rosenblatt, an eldercare attorney and registered nurse. She and her husband, a psychologist, founded AgingParents.com and AgingInvestor.com to help families and financial professionals sort through such issues with aging adults.

Everyone over age 65 should be planning for the end and for the gray zone of incapacity that often precedes it, Rosenblatt says.