Delegated Investment Managers: Challenges Yield Mixed Results

Delegated 401(k) investments have been an infrequent target of litigation. This quarter, we saw three cases in that area. In delegated situations, plan fiduciaries retain an investment advisor as an investment manager to implement a plan’s investment policy statement and make individual investment decisions as a fiduciary to the plan. Plan sponsor fiduciaries are responsible for monitoring the delegated investment manager.

- $124.6 million fiduciary liability. A global outsourcing firm had a retirement plan with separate participant-directed 401(k) and profit-sharing components. Total plan assets were more than $1 billion, and the profit-sharing side held about half of the total. The plan’s fiduciaries were responsible for investing the profit-sharing assets and retained a delegated investment manager to manage those assets. The plan sponsor fiduciaries authorized the investment manager to use its non-diversification strategy for 100 percent of the profit-sharing assets, which it did. This was in direct conflict with ERISA’s clear mandate that “fiduciaries shall diversify the investments of the plan so as to minimize the risk of large losses.” At one point, more than 45 percent of the profit-sharing component’s assets were held in the stock of a single company: Valeant Pharmaceuticals. In a six-week period, the Valeant stock lost 61 percent of its value.

The U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) investigated and sued the investment manager and the other plan fiduciaries. Scalia v. Ruane, Cunniff & Goldfarb (S.D. NY filed Oct. 2019). The investment manager was sued for failing to diversify the profit-sharing investments to minimize the risk of large losses, as mandated by ERISA. The other plan fiduciaries, including the individual committee members, were sued for failing to properly monitor the investment manager’s activities, including its non-diversified approach. The case was recently settled for $124.6 million. Allocation of the settlement liability among the fiduciaries has not been disclosed.

This case is a reminder that in delegated situations, plan fiduciaries must monitor the work of their discretionary investment managers and be aware of how they are investing plan assets and meeting ERISA investment standards.

- $9.5 million fiduciary settlement. A pharmaceutical company retained a delegated investment manager to manage the investments in its 401(k) plan. Early in its work, the investment manager moved most of the plan’s investments into its proprietary collective trust investments. Approximately four years later, plan participants sued the investment manager, alleging that it acted in its own interests rather than for the plan’s participants and beneficiaries. The investment manager denied these allegations. The other plan fiduciaries, including committee members, were sued for permitting the investment manager to use only its proprietary collective trust investments, which had a short performance history. They were also sued for paying excessive investment expenses.

Soon before trial, the case was settled for $9.5 million. Miller v. Astellas US LLC (N.D. Ill. filed July 2020).

- Plan fiduciaries settle for $12.5 million—Delegated investment manager wins. A suit with allegations similar to Miller v. Astellas was filed against Lowe’s Home Improvement and its delegated investment manager. The Lowe’s fiduciaries settled for $12.5 million after three years of litigation. The suit against the delegated investment manager proceeded to trial, and the investment manager won. The decision was upheld on appeal. Reetz v. Aon Hewitt Investment Consulting, Inc. (4th Cir. 2023).

ESG Cases Begin

Plan participants sued American Airlines for including funds that advance environmental, social, and governance (ESG) causes in their 401(k) plans. The complaint broadly alleges that ESG funds violate ERISA because they support objectives other than plan participants’ financial security in retirement. However, it does not provide specifics. It also alleges that many of the socially responsible funds offered are more expensive than—and underperform—non-ESG funds.

The complaint identifies 25 ESG funds as being in the American Airlines plans. This seems unlikely unless the plaintiffs have included ESG funds available in the plan’s self-directed brokerage account. From a recent Form 5500 for the American Airlines 401(k) plans, it is not apparent that any of the ESG funds identified are in the plans. It is generally accepted that plan fiduciaries are not responsible for the investments offered in properly structured self-directed brokerage programs. Spence v. American Airlines (N.D. Tex. filed June 2023). It will be interesting to see if the court addresses the availability of ESG investments in self-directed brokerage programs.

This suit is filed against the regulatory backdrop of frequently changing standards announced by the DOL for the use of ESG investments in retirement plans. Although the DOL’s position has varied, the underlying ERISA requirement that plan fiduciaries act exclusively in the best interests of participants and beneficiaries in their plans has not changed since its adoption in 1974.

401(k) and 403(b) Fee Cases Continue

The flow of cases alleging fiduciary breaches through the overpayment of fees and the retention of underperforming investments in 401(k) and 403(b) plans continues, with one new twist. Here are a few updates.

In the last quarter, at least 15 court decisions were issued on motions to resolve fees lawsuits. Some cases were decided in fiduciaries’ favor, and others will proceed.

Here are three notable recent cases:

- In the first case of this type to be decided by a jury, the plan fiduciaries won—or at least they had no liability. Fiduciaries of Yale University’s 403(b) plan were sued for mismanagement of the plan, including overpaying administration fees, retaining expensive and poor performing investments, and offering too many investments. The jury found that the plan fiduciaries breached their duty of prudence by allowing unreasonable fees to be charged, and that their actions resulted in a loss to the plan. However, they also found that prudent fiduciaries could have made the same decisions. In the end, the jury found that no losses were proved by the plaintiffs. The fiduciary won outright on the investment issues. Vellali v. Yale University (D. CT 2023)

- A second case includes the now-familiar claims of overpayment for recordkeeping and investment fees. It goes on to allege that, by using revenue sharing to pay for plan recordkeeping, the fiduciaries discriminated against plan participants who invested in funds that produced revenue sharing. Investors in the revenue-sharing funds are effectively paying the recordkeeping fees of participants in the non-revenue sharing funds. To date, we have not seen a court rule on this issue. Zimmerman v. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (C.D. Cal. filed June 2023).

- Another of the suits challenging the use of BlackRock’s LifePath target-date funds has been dismissed. The judge held that a meaningful benchmark was not provided in the complaint. The LifePath funds are index funds that become more conservative up to retirement, but not through or past retirement. Two of the four comparison funds were actively managed, and although the other two were indexed, they continued to become more conservative through retirement. The judge concluded that, “the complaint fails to take a claim of fiduciary duty violation from the realm of ‘possibility’ to ‘plausibility.’” Luckett v. Wintrust Financial Corp. (N.D. Ill. 2023).

Plan Sponsors Have Wide Discretion in Severance Plan Design

After layoffs at Northrop Grumman, some employees received severance benefits, and others did not. Disappointed, laid-off employees sued. The Northrop Grumman severance plan provides that those who work at least 20 hours per week are eligible for benefits if they receive a personally addressed memo from a vice president of Human Resources. The employees who did not receive severance benefits had not received a required memo. They contended that the memo requirement was only a ministerial act confirming the eligibility of those regularly scheduled to work at least 20 hours a week.

The district court found in favor of the company, noting that the plan document gives the human resources department discretion to decide who, if anyone, receives severance benefits, as ERISA permits. The disappointed former employees appealed. The appellate court affirmed the decision in favor of Northrop Grumman. The court pointed out that the design of a plan, which may include discretion, is not a fiduciary function. But administering a plan according to its terms is a fiduciary function. As the judge said, “A plan sponsor always may, indeed always must, apply a pension or welfare plan as written.” Carlson v. Northrop Grumman Severance Plan (7th Cir. 2023).

Health Plan Fiduciary Claims Ramping Up

We have been reporting on the veritable avalanche of 401(k) and 403(b) plan fee-related cases for years. So far, there have been few cases alleging fiduciary breaches in connection with health plans. That appears to be changing.

The Schlichter law firm, which filed the first group of 401(k) fees lawsuits in 2007 and 2008, has been using social media to identify “current employees who have participated in healthcare plans” at Target, State Farm, Nordstrom, and PetSmart. The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 and newly issued regulations with transparency requirements for health plans appear to be the foundation for potential claims.

There is also an increasing number of claims by plan sponsors against third-party administrators (TPAs). For instance, Kraft Heinz has sued its TPA under ERISA for improperly overpaying claims and failing to turn over plan data in connection with processing claims, among other things. Kraft Heinz Company Employee Benefits Board v. Aetna Life Insurance Company (E.D Tex. filed June 2023).

These pages will not include detailed reporting on fiduciary issues in the health space. Plan sponsors and fiduciaries are encouraged to consult with their healthcare advisors.

A nonprofit mission statement is a short and precise declaration of the organization’s purpose in society. And its values are the principles that guide how the organization thinks and acts. While a mission statement explains the organization’s reason for existing, values describe its culture and beliefs.

Although some foundations are established to mobilize funds around a single, specific, and unchanging mission, many others must retroactively develop or reorganize their mission and values as the organization evolves. Private and family foundations—which often have asset pools before they develop mission statements—are particularly vulnerable to misalignment without a clear and sustainable direction for their philanthropic endeavors.

“Especially as leadership shifts from one generation to another, it’s important for foundations to have a steady vision of what they want to achieve and to define that vision through their mission and values,” says CAPTRUST Director of Endowments and Foundations Heather Shanahan. “Otherwise, different leaders may have very different opinions on how to spend, which can create gridlock or dilute impact over time.” Without clarity of purpose, foundations may also experience a multitude of causes vying for their attention, leading to confusion and uncertainty.

A well-designed mission and values can do the opposite. Namely, they help foundation leaders and staff move together in a shared direction.

Mission Driven

“While mission and values are intertwined, they each serve a distinct purpose,” says CAPTRUST Financial Advisor Luis Zervigon. Zervigon advises endowments and foundations, works on multiple community boards, and serves as a trustee of both the Keller Family Foundation and the RosaMary Foundation in New Orleans, Louisiana. He says one of the biggest benefits of having a mission statement is that

“it helps the foundation think proactively.”

A mission-driven approach emphasizes long-term vision and desired impact. It defines the causes and issues the foundation aims to address by identifying its goals and target beneficiaries. “The mission lays the groundwork for subsequent decision-making,” says Shanahan.

Creating a mission statement allows founders to engage in strategic planning and align their short- and long-term philanthropic goals. It also helps outline the foundation’s focus, creating the potential for deeper impact.

Nonprofits that are drafting—or revising—mission statements can begin with two key steps. First, reflect on the foundation’s purpose. For foundation leaders, this means evaluating long-term aspirations, understanding the legacy of the group, and assessing the external needs and opportunities that align with their resources and expertise.

Next, board members may choose to perform a SWOT analysis with key stakeholders, assessing the organization’s internal strengths and weaknesses, plus external opportunities and threats. A SWOT-based stakeholder analysis can help identify areas of focus and potential alignment between the foundation’s resources and its community’s needs.

Throughout this process, it can be helpful to remember that developing a mission is iterative. Leaders should draft initial statements, seek feedback from stakeholders, then refine accordingly. “The ideal mission statement allows flexibility over time while creating healthy limits,” says Shanahan. “It demonstrates what the foundation does and does not do, and it gives leaders a reference point when evaluating opportunities.”

Zervigon says he’s seen many foundations move from generalist giving to special-interest-based missions. For instance, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation—now known for its fight to end malaria—was founded in 2000 with four initial priorities: global health, education, libraries, and the Pacific Northwest. In 2006, it reorganized, creating three separate divisions. One addresses global development; another addresses global health; and the third addresses social inequities in the U.S. The U.S. program also identifies emerging societal needs that currently fall outside the program’s scope but could become areas of focus in the future.

Another example is the Surdna Foundation, founded as a family foundation in 1917 to address a broad range of philanthropic purposes. But by the 1990s, Surdna’s focus had narrowed considerably, addressing mainly environmental and community revitalization needs. In 2008, the foundation adopted an all-new mission statement focused solely on social justice. According to its website, this decision was intended to “create a sense of common purpose and help build consensus around difficult choices.”

Value Development

Zervigon says core values can provide a similar sense of purpose and consensus. And sometimes, they can offer additional specificity. “While the mission is a useful tool for creating guardrails, values can provide a framework within the mission to help leaders put priorities in order,” he says. Naming core values can help leaders discern which projects and efforts to support, in which order.

For instance, the mission of the RosaMary Foundation is to support grant seekers in Greater New Orleans who share the foundation’s vision to build a successful and vibrant city. Under that mission, it gives highest priority to grants in five categories, ranging from education and human service organizations to governmental oversight activities. These classifications help foundation leaders prioritize grant applications.

A value-driven approach can also be helpful for foundations that have outdated mission statements or trust documents. “Often, these groups simply follow an organic process of letting the trustees decide what is the greatest need in their community,” says Zervigon. And that’s OK too. But for foundations that want a list of values, looking at past decisions can reveal patterns of giving. For instance, if the organization finds itself consistently giving to community development and to the arts, then those may be its values.

Nonprofits typically have three to seven core values. What’s important is not the specific number but making sure that all leaders agree on what should be included. Also, value statements should not be aspirational. They should be grounded in the real experience of the foundation or the culture of its board. Once the foundation knows its own values, it’s easier to identify like-minded grant seekers.

Natural Evolution

Once mission and values have been established, implementation and evolution become critical, ensuring that the foundation’s efforts remain aligned with its purpose and adaptable to change. Foundation leaders must actively steer the organization toward the foundation’s intended impact while embracing the evolving philanthropic landscape.

“Ideally, mission and values will work together, guiding the foundation’s grantmaking strategies and decisions,” says Shanahan. “Aligning funding opportunities with these two elements can help ensure the efficient allocation of resources and maximize the foundation’s impact.”

Zervigon agrees. “Mission and values provide a framework, but it is through strategic grantmaking that foundations truly manifest their impact,” he says. “By allocating resources in alignment with their mission and values, foundations can more effectively address societal needs and drive positive change.” Strategic grantmaking allows foundations to leverage their unique perspectives and expertise to target pressing issues. It empowers them to be change agents in their communities and beyond.

However, as time progresses, both the external landscape and a foundation’s priorities are likely to evolve. This is one of the reasons why foundation leaders should periodically assess the effectiveness and relevance of their mission and values. “The evaluation process allows for adjustments and refinements to ensure continued alignment between the outside world and the foundation’s goals,” says Shanahan.

Each foundation’s journey is an ongoing process of growth. “Regular evaluation helps us stay true to our core principles while embracing new possibilities,” says Zervigon. “It enables foundations to be proactive and nimble in their approaches to philanthropy.”

Especially for family foundations, the generational transfer of leadership can be a natural time for evaluation. Some families choose to involve younger family members very early in the process, educating them about the mission and values so they’re ready to take the reins when the time comes. Engaging next-generation leaders before they become board members can help ensure a smooth transition.

It also creates continuity of purpose and helps the organization stay relevant in a changing world. This can help strengthen the group’s long-term impact. Whether those next-generation leaders are family members or professional staff, each successive generation will contribute to the foundation’s growth and continued relevance, but only if they understand and feel connected to its mission and values.

For leaders of private and family foundations grappling with the question of which comes first—mission or values—the answer lies in recognizing their interdependence. By engaging stakeholders, reflecting on purpose, conducting analyses, and embracing an iterative process, leaders can create mission and value statements that are fit to guide a multigenerational philanthropic journey. Implementing and regularly evaluating these statements will ensure ongoing alignment and adaptability, helping the foundation to achieve its intended impact and fulfill its purpose.

Q: I bought whole life insurance when my kids were little. Do I still need it?

In brief, maybe you don’t. If your kids have finished college, your mortgage is paid off (or you plan on downsizing), and your retirement savings are on track, you may no longer need your life insurance policy. Still, there are reasons you might want to keep it.

For instance, consider that—simply due to aging—you are now at a higher risk of health complications. Even with health insurance in place, it’s easy to amass tens of thousands of dollars of uncovered healthcare expenses, especially if you need long-term care. Life insurance is one way your spouse and heirs can replenish any depleted savings accounts after these expenses are paid.

You can also use life insurance to pay for estate taxes. Typically, this is done by establishing an irrevocable life insurance trust (ILIT), which is shielded from creditors and the Internal Revenue Service. Or you can leverage life insurance to leave an inheritance for your loved ones by naming them as the beneficiaries of your policy. Another option is to sell the policy through a viatical settlement, but there are some very specific requirements you’ll have to meet before this can happen. Also, a viatical settlement is only recommended if the lump-sum payout you’ll receive is more than the cash value of the policy.

No matter what you decide to do, talk to your financial advisor to be sure your actions are aligned with your financial goals. If your policy is paid up so you’re no longer paying premiums, then you won’t have to do anything to keep it, so you might as well get the full benefit from it. An advisor can help you understand the best way to do that.

Q: Can you explain how FDIC insurance works?

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) offers insurance coverage to banks as a way to protect your cash deposits against the risk of bank failure. The standard insurance amount is $250,000 per depositor, per insured bank, for each account ownership category.

In other words, if you have multiple individual accounts at the same bank, the combined total of these accounts is protected up to $250,000. However, if you have more than $250,000 spread across multiple individual accounts at the same bank, only $250,000 would be insured.

Banks aren’t required to participate in FDIC insurance, and they aren’t insured automatically. They apply for coverage and pay monthly premiums, just like you pay for your health or auto insurance. Banks that choose not to participate in FDIC insurance are extremely rare, but they do exist, so it’s a good idea to confirm that your bank is a member.

Credit unions use a separate form of insurance offered via the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA) instead. NCUA coverage is similar to FDIC insurance coverage, guaranteeing up to $250,000 per person, per institution, per ownership category.

To take full advantage of FDIC or NCUA insurance, consider spreading your cash deposits across multiple banks and diversifying your account ownership. These two strategies can help you increase your total insured amount at each bank. And if you’re uncertain about how much cash you should have in checking and savings accounts, talk to your financial advisor.

Q: I work at a company that gives me stock as part of my retirement plan. A friend told me about NUA. How does that work?

Net unrealized appreciation (NUA) is a tax strategy that allows you to convert what would usually be considered ordinary income into long-term capital gains instead. Since income tax rates can go as high as 37 percent (plus applicable state income tax), but long-term capital gains tax is capped at 20 percent, this swap can make a big difference to your tax bill.

The strategy allows you to claim long-term capital gains on the difference between the current value of the company stock in your retirement plan and its price when it was originally acquired, also known as its cost basis.

One of the other advantages of this strategy is that you do not have to pay both types of tax—income tax and capital gains tax—at the same time. Although income tax will be due when you take your stock out of your company’s retirement plan, the long-term capital gains tax on appreciation above the cost basis, known as net unrealized appreciation or NUA, does not happen until the appreciated stock is sold.

Of course, an NUA strategy won’t be the right move for everyone. Your plan may not have the necessary features available, or you may not have a low enough cost basis. Also, NUA can only be done after certain triggering events, and you have to follow specific rules to capture the benefits.

As always, the best idea is to consult your financial advisor or tax professional. They can help you understand whether an NUA strategy is suitable for your circumstances and what next steps you’ll need to take.

An avid home canner for more than 15 years, Weigl goes to great lengths to acquire a stock of ripe fruit to make preserves every summer. Figs are expensive and can be difficult to find in large quantities. Plus, fresh-picked figs beat store-bought figs any day. “In the South, fig trees are plentiful, but many people don’t know what to do with them,” she says.

“Until recently, my octogenarian neighbor and I would stalk the fig trees in our neighborhood,” she says. Each day, her late friend Ralph, a master gardener who lived across the street, would track the ripening of each neighbor’s trees—people who were obviously not picking their figs. When the branches were heavy and laden, he would text her: “Lilian’s trees are ready to be picked,” or “The Moody’s fig tree is looking good.”

Of course, their neighborhood fig watch was polite. “We always asked permission,” says Weigl. Once they had it, they’d pick figs by the pound and freeze them at peak ripeness. Later, Weigl would methodically process them in her water bath canner, turning them into lovely jars of luscious preserves.

Sadly, her partner in figs passed away earlier this year. Weigl says she misses Ralph terribly, but the jars that line her shelves are full of beautiful memories.

Bittersweet Longing

Home canning is an almost-magical process that turns humble fruits and vegetables into delectable treats that far outshine mass-produced jellies and pickles. Canning, pickling, and fermenting have surged in popularity with a new generation of foodies who didn’t necessarily grow up with these kitchen skills but delight in acquiring them. The homely acts of washing, chopping, simmering, and stocking a pantry can be a balm for the mind at a time when news reports are filled with calamities.

“I see, within myself and my peers, this nostalgia for the homemaking skills that our grandmothers and mothers had. We want to master these skills, not out of necessity but just out of the desire to have them,” says Weigl. She recalls a similar resurgence of interest in food preservation as a hobby around 2008, when mass anxiety about the markets and economy spurred a desire to get back to basics—to plant gardens and make pickles from seasonal fruits and vegetables.

“I do think canning is having a moment, probably related to the pandemic when we were all stuck at home, looking for things to do, and wanting to be self-sufficient,” says Weigl.

A Healthy Connection with Food

Nikki Evers, a real estate agent in Folsom, California, makes her special salsa from jalapenos, bell peppers, and onions and gives it to her friends and family. She grows her own peppers, then enhances their goodness by fermenting them in a salt and water brine. “The natural lacto-fermentation process cultivates good bacteria,” says Evers. She puts her salsa on eggs or in salad dressing. “It’s really good for your gut health because when you eat it, you introduce healthy microorganisms into your system.”

While Evers’s mother, aunts, and grandmother all knew how to preserve food, Evers didn’t become a canning and fermenting enthusiast until she was in her 40s and faced some troubling health issues. A marathon runner who had always been a healthy eater, “I started to get sick with stomach issues, inflammation, and achy joints,” says Evers. She found it puzzling that her doctor’s prescription medications couldn’t quell her bothersome symptoms. In fact, they didn’t resolve until she committed to some major changes in her style of eating.

A self-proclaimed “food nerd,” Evers began reading everything she could find about the science of gut health and the nutrients in organic, heirloom vegetables. “I wanted to have a direct relationship with my food.”

She began to grow much of her family’s food herself on their 10 acres. The large garden she has developed is both her dream and her salvation. Learning to grow and preserve tomatoes, peppers, cabbage, and other vegetables from her own land has given her the ability to eat healthy and seasonal foods all year round.

Each year, she looks forward to starting her seedlings indoors in winter, using grow lights. By mid-March, she’ll have 320 plants in her house. “It’s very satisfying to have a little seed that I planted in a container in my house, then put it in ground when the season allows,” says Evers.

“From July to September, I’m in my garden for two hours every morning,” says Evers. “I bring in the vegetables I’ve harvested, and that determines whether I’m going to can tomatoes or do fermenting that day. I’ll can and preserve in the evenings, making sure the vegetables don’t sit too long. Even if you have a small backyard, you can still plant a garden and benefit from growing your own food.”

Getting Started

Most beginners do what’s called water bath canning, which is a safe method for processing foods with high acid content. This includes most jams, jellies, pickles, and chutneys. These recipes typically include an acid, such as vinegar or lemon juice, and are brought to a boiling temperature to eliminate any potentially harmful bacteria.

Low-acid foods, like meats, poultry, or soups, require a more advanced method that uses a pressure canner to reach temperatures of 240 degrees or higher. You can find detailed information on food safety and canning methods by searching for the words home canning on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website.

As a general rule though it’s always safest to use tested recipes from reliable sources because old-fashioned recipes aren’t always up to modern food safety standards. For example, a family recipe from generations ago may call for sealing jars with paraffin, but this material can develop pinholes and let bad bacteria in, says Weigl.

Water bath canning requires some basic equipment:

- Pint- or quart-sized canning jars, such as from Ball, Anchor Hocking, or Weck

- Canning lids

- A water bath canner—essentially a large, deep pot with a lid and a rack—available at suppliers like Ace Hardware or Walmart and often packaged in a kit together with other essential tools

- A rack and dividers for holding the jars

- Tongs for placing and lifting jars

- A funnel for filling jars

- A small ruler

An easy first canning project is homemade strawberry jam. The Ball brand offers a low-sugar strawberry freezer jam recipe on its website at ballmasonjars.com, and numerous other beginner recipes are available online. “It’s the perfect entry point for lots of people. Homemade strawberry jam is 10 times better than anything at the store, and it’s a fleeting fruit,” says Weigl.

But the Giving Pledge is open only to billionaires—2,540 individuals worldwide, according to Forbes’ most recent list—or to those who would have billions if they hadn’t already given so much away, as are the handful of similar pledges that follow similar philanthropic principles. For instance, some billionaires who find the Giving Pledge too modest have made a different vow to give away at least 5 percent of their wealth each year.

The core idea among these pledges is that great wealth should benefit the collective good, not only a small number of family members. And that’s a principle that anyone can follow, billionaire or not.

In fact, financial and estate planners say giving away most of your money is something that anyone with significant assets can consider—although few do. “In my experience of 22 years, it’s exceedingly uncommon,” says Eido Walny, a Milwaukee lawyer who serves on the board of directors of the National Association of Estate Planners and Councils.

Mike Gray, a CAPTRUST financial advisor based in Raleigh, North Carolina, says that while many people include charities in their estate plans, most have a family-first mentality, leaving most of their wealth to their adult children. But some people do put charity first. For instance, one couple that Gray works with plans to give away about $25 million, most of their assets, upon their deaths.

Meet the Phillips

David and Adele Phillips (using pseudonyms to protect their privacy) first met through a civic club and found they had a lot in common. Married for more than a decade now, David, 79, and Adele, 52, have no children. They live an active outdoor life dedicated to faith, community service, and each other.

The plan to give away most of their money, they say, has evolved over the years but has been driven by those values.

“Charitable work has always been a part of our lives,” says David, who made his money in real estate and banking. Adele, who inherited some of her wealth and still works in order to maintain her independence, says she has volunteered since childhood. “My grandfather was a pastor, so service was a very big part of our family.”

With that background, Adele says, “It would never occur to us to spend everything we have on ourselves.”

David and Adele have always been active fundraisers and donors. But the plan took on extra urgency, David says, after he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 2016 and was told he might have just a few years to live. While he’s outlived that initial prognosis, he says the experience “helped me realize I probably should get my plan in order.”

Right now, the Phillipses plan to give money to several charities, including a local nature conservancy, the schools and colleges they attended, and the civic club where they met. They are also planning bequests to a few extended family members.

The Phillipses developed their plan in partnership with their financial advisors, as well as an estate attorney, a certified public accountant, and an executor. They call this their A-team and call the executor their quarterback. “Our plan is solid,” David says, “and everyone knows who will take the lead when the time comes.”

Planning a Major Legacy

Inspired by the Giving Pledge or the Phillipses? To follow in their footsteps, you’ll need a plan and a team to help you execute it. “There are a lot of different ways to go about this,” Walny says, and it’s more complicated than just updating a will.

Wills, in fact, may not be the best way to make major bequests, in part because the probate process can put unwanted public focus on your estate, says Walny.

Other, potentially more efficient, ways to boost lifetime giving or leave assets behind include setting up trusts, creating a family foundation, or putting money in a donor-advised fund (DAF). A DAF is a charitable investment account, administered by an established nonprofit organization. Donors recommend gifts from their accounts but don’t directly control the money. For many people, a DAF is more appealing than a family foundation because it eliminates administrative expenses and duties, Walny says.

However, control of both family foundations and DAF accounts can be passed down to heirs, if that’s desired, giving adult children and other family members asset pools to meet their own charitable goals.

Some people also choose to name different charities as the beneficiaries of each of their assets, such as life insurance policies or retirement accounts. Designating a charity as the beneficiary of a traditional individual retirement account (IRA) can be an especially smart move because otherwise your heirs will pay income taxes on the proceeds. “Going this path doesn’t change the amount the charity receives but effectively increases what the heirs will net,” Gray says.

Choosing Charities

Most people know what they are passionate about, so choosing which causes they’ll support isn’t a difficult task. But it can take some homework to vet specific organizations that support those causes. Groups such as Charity Navigator and Charity Watch are good sources of information, according to Consumer Reports.

Even if you’ve designated a recipient, it’s smart to dig deeper, Walny says. Anyone planning a major gift should meet with charity administrators to talk about how they might align their philanthropic intentions with the group’s needs.

He had one client, he says, who wanted his money spent on guide dogs—until the recipient organization told him that the dogs attracted so many donations that they were “living in 24-carat-gold dog houses,” while other programs were severely underfunded. The donor opted to redirect his money to those needs. In other cases, a small nonprofit may not be able to fully capitalize on a large gift if it’s a surprise, so starting the conversation early can ease the planning process for both giver and recipient.

Giving While Living

Sometimes, it makes more sense to give now instead of giving after your death. Of course, there are tangible tax benefits to giving while you’re alive. Some lifetime gifts, including charitable ones and those that pay direct educational and medical expenses, are exempt from annual gift and estate taxes, and there is no limit to how many such gifts you can make. By reducing the size of your estate, you also reduce the federal estate tax your heirs will pay.

But there is also the intangible benefit of witnessing your positive impact on the world. Also, the causes you care about may need the money sooner rather than later.

Still, Walny says, most people are concerned about running out of money by giving too much away while they’re still alive. A financial advisor can be a helpful resource in figuring out how much and how often you can give and how much you will need to conserve.

For those who are considering large-scale philanthropy, Gray says, it can also help put your mind at ease to remember that your giving plans are flexible. “So long as you’re alive and mentally competent, you can generally change your mind about where your money goes or how much you will donate.”

This is a problem that Marti DeLiema, a University of Minnesota researcher, has spent years trying to solve. In her research, DeLiema surveyed and interviewed thousands of older adults and heard stories about losses ranging from $50 to millions of dollars in scams perpetrated over the phone, through email and social media, and on the internet. Some of the worst ones involved investment-romance scams, in which schemers acted romantically interested in their victims.

In one scenario, the con artist talked about how he “just made half a million dollars in a crazy new coin offering on a crypto exchange.” He was charming and flirtatious, offering to share the opportunity with the other person, DeLiema says. They had multiple long conversations. But it seems he had the same conversations with numerous people.

Victims sent money, and “when the scam finally unraveled, the older adults had lost thousands of dollars, as well as a person they had a deep romantic connection with. It’s a double whammy of pain,” says DeLiema, an interdisciplinary gerontologist and an assistant professor in the School of Social Work at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities.

Enlisting a financial ally, often a family member or close friend, could be the best defense against these attacks and other fiscal missteps, DeLiema says.

A financial ally, sometimes called a financial advocate, is someone who assists you in managing your financial responsibilities, like paying bills and taxes, filing insurance claims, monitoring retirement accounts, and applying for government benefits. Financial allies can run interference on other potential problems as well.

“There are many examples of financial exploitation or abuse by people who misuse an older person’s debit and credit cards, forge signatures, improperly transfer property, or change beneficiary designations,” says DeLiema.

Almost everyone knows at least one friend or family member who has experienced identity theft or financial fraud. In the investment-romance scam, a financial ally “might not have stopped the first $1,000 from leaving the account, but they could have prevented the deep-pocket losses,” DeLiema says.

An ally could be a spouse or partner, an adult child, a grandchild, a niece or nephew, a close friend, a fellow church member, or a paid professional, such as a trust officer, attorney, or accountant. Generally, this should be someone you have known for a long time and are sure you can rely on to make good decisions.

“Your ally is someone you can depend on to have your best interest at heart,” says John Keeton, a CAPTRUST financial advisor in San Antonio, Texas. “You can lean on them to help you make well-informed decisions. This sets the groundwork for your ally to take on more responsibilities if you start to lose interest in decision-making or experience some cognitive decline.”

Cathy Seeber, a CAPTRUST financial advisor in Lewes, Delaware, agrees. She says many advisors will ask clients to name a trusted contact in case questions arise and the client is unreachable or seems to need financial intervention.

Similar to a financial ally, a trusted contact is someone your financial institution is authorized to communicate with if you’re unavailable. “Ideally, this contact will have a close relationship with your financial advisor, who is often the first one to notice unusual transactions or behaviors,” Seeber says.

Selecting the Right Person

Although some people remain financially sharp as they age, many will experience some cognitive decline, dementia, or an illness that impacts their ability to make critical choices. And those who don’t are still at risk of financial mistreatment, as new methods of money transfer; new markets, such as cryptocurrency; and new types of communication technology allow scammers to target thousands of people simultaneously.

To help people navigate these issues, DeLiema and her colleagues created the Thinking Ahead Roadmap, a website and booklet, which provides a step-by-step guide to keeping money safe as you age. One of its strongest recommendations: Identify a financial ally by the time you retire, or sooner.

When it comes to selecting the best candidate, people often automatically select their spouse or partner as a first choice because they believe that person understands their finances and will put their needs first. But because of the likelihood of serious health issues or the loss of a partner, DeLiema recommends that everyone choose a backup ally as well—someone who is organized and reliable. This should be someone you’re comfortable being honest with and who will listen to you.

At first, the person might play a consulting role and offer guidance only when asked. In these early stages, they can act as a sounding board and provide assistance if you think you’ve been the victim of fraud or exploitation. Your ally can then assume additional responsibilities over time as their competence grows and as they become more familiar with your financial situation.

However, unless you give them legal authority via a financial power of attorney (POA), they will not have the power to act on your behalf. A financial POA is a legal document that gives someone the right to make decisions about your money and property. DeLiema suggests preparing a POA document early on but signing it only when you think you need regular assistance with daily tasks, such as paying bills and taxes and monitoring investments.

It’s a lot of responsibility, so you want to select the right person to take the driver’s seat at the right time, instead of leaving things to chance. “If you don’t make a decision, you may be manipulated into giving power of attorney to a child who should never be trusted with money,” DeLiema says.

Most parents know which of their children they can rely on to make good financial decisions and which ones they think might try to cash in early on their inheritance, she says. In one interview, DeLiema says a woman told her that she clearly understood her adult son’s limited financial decision-making capabilities and her own responsibility to protect herself in light of them. The woman asked, “If he can’t take care of his money, how is he going to take care of our money?”

Navigating Family Dynamics

Instead of choosing just one contact, some people choose to enlist two or more people as their financial allies, Seeber says. “It’s almost like having a personal financial board of directors.” A small group of people working together can also reassure other family members and friends that decisions are being made in the individual’s best interest, she says.

For example, Seeber knows one elderly woman who was experiencing short-term memory loss and turned over control of her finances to a son who lived nearby. But a second son, who lived farther away, was also given access to all her accounts so that he could keep an eye on transactions. “This way, they share accountability,” Seeber says.

When one adult child is given the authority to supervise a parent’s finances, it can cause hard feelings between siblings. But there are ways to navigate these dynamics by giving everyone separate responsibilities, says Keeton.

For example, you might ask the most monetarily savvy adult child to take over your finances while calling on another to be responsible for healthcare issues and asking a third to plan family events, he says. “You can build a role for each child, based on their interests.”

DeLiema recommends bringing your family together to tell them about their potential roles in a single group discussion. This way, everyone will know the plan comes straight from you, reducing the risk of future disagreements about how you want your money managed and by whom. She also advises walking your allies through your current accounts, assets, income, expenses, liabilities, and long-term goals.

Building the Foundation for Success

Throughout the process, communication is key. Your ally will need guidance to understand and accomplish what you’re trying to achieve, says Keeton. “Think of the ally as the family’s chief financial officer. You may want to consider coaching your children to manage the family finances. And ideally, you would phase them into that role, not just give them the keys overnight.”

You can lay the groundwork when your children are young by teaching them about earning, spending, gifting, and saving, he says. Consider letting them use kids’ financial apps, like Greenlight, PiggyBot, or iAllowance, to organize their budgets and track their spending. “It’s a great way to develop financial awareness and acumen,” says Keeton.

Keeton recommends people introduce their financial ally to their financial advisor. Adult children can be included in financial planning sessions and tax meetings to show them what you’re trying to accomplish and how you think through big decisions, he says.

Some people are uncomfortable sharing financial information with others, including their children. “One fear I’ve heard is that people don’t want to disclose the scope of their wealth to their adult children out of fear that their children will choose to live a more lavish lifestyle or won’t pursue their own career goals knowing how much they are going to inherit,” DeLiema says.

Utilizing the services of a corporate trustee is an alternative option if you feel that your family members aren’t well-equipped to manage your estate. “This trustee will have a fiduciary responsibility to ensure that decision-making is aligned with your overall estate plan,” says Keeton. Eventually, your ally could become well-positioned to be the executor of your will, he says.

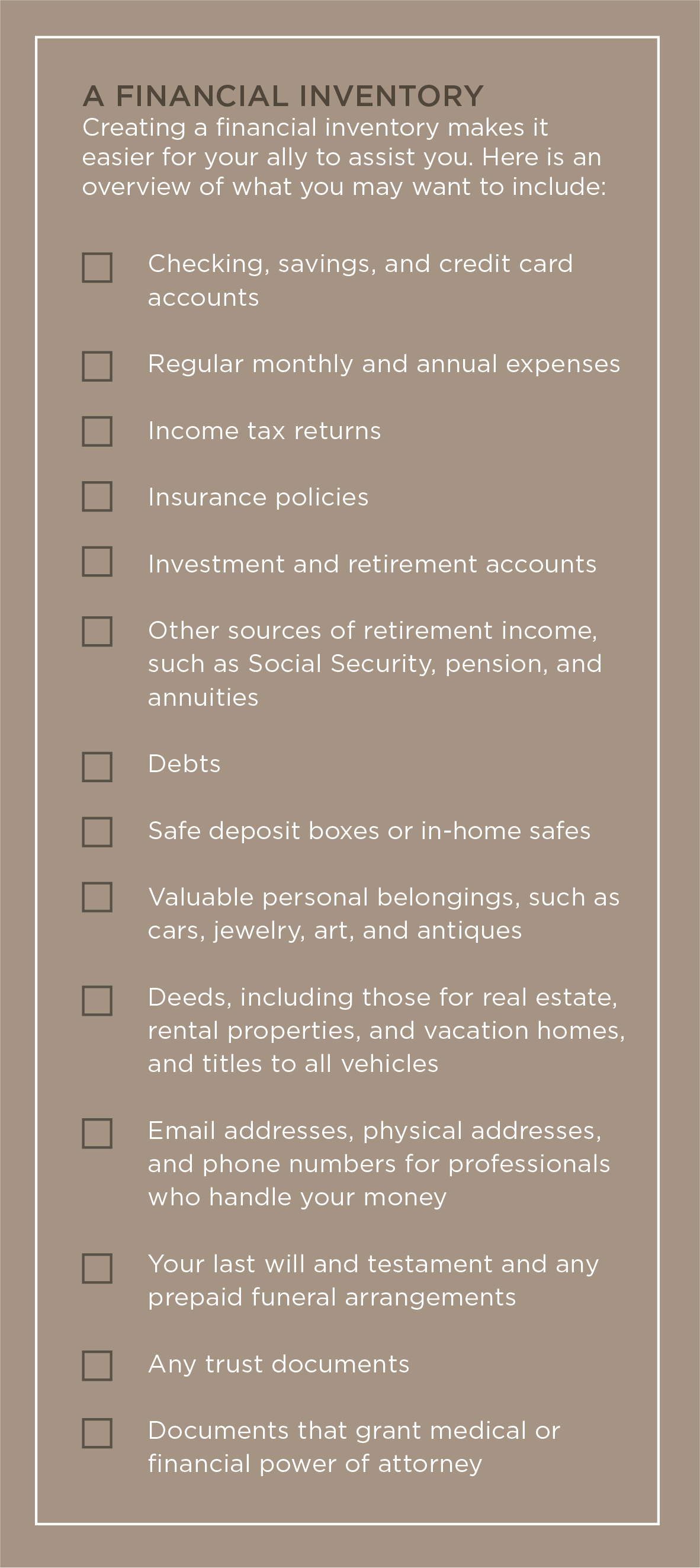

To make things easier for your ally, DeLiema recommends simplifying your finances as much as possible and creating an inventory of your income, debt, and other money needs. Keep this information in one place to make it easier for this person to assist you in the future.

Most people who have a designated financial ally say the arrangement gives them confidence and peace of mind. “For many people, it’s a huge relief not to have to manage their day-to-day financial matters when things become challenging,” says DeLiema.

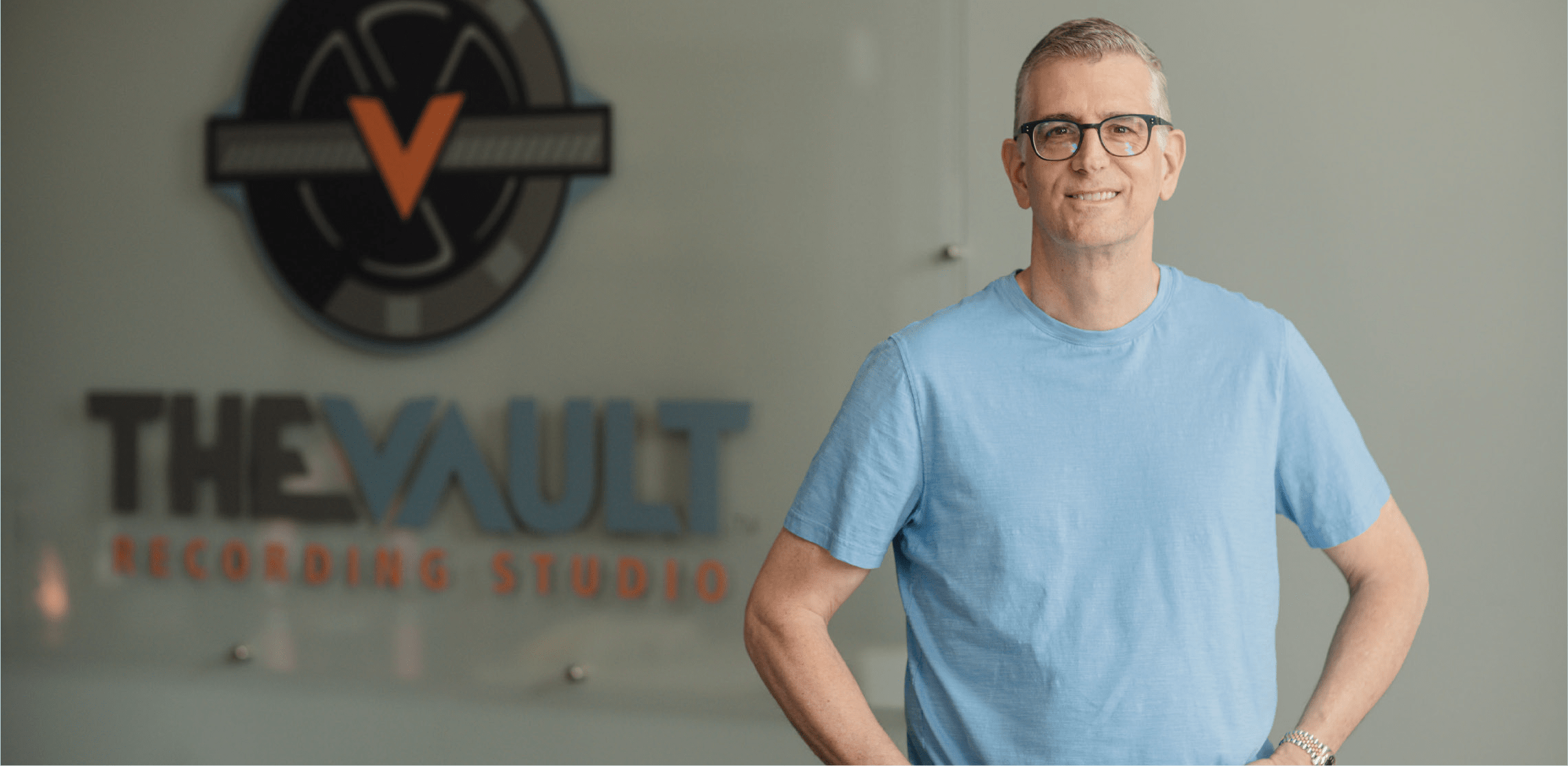

In 2018, McCutcheon left his position as the U.S. industrial products and Pittsburgh office leader at PwC, one of the Big Four accounting and consulting firms, to turn his family hobby, The Vault Recording Studio, into a commercial venture.

As founder and president of The Vault, McCutcheon found the ideal track for his second act.

“I learned early on that I had an artistic, creative side to me,” he says. “In the world of art, it’s called creativity. But in the world of business, it goes by a different name. It’s called innovation. It’s your ability to see the abstract and bring it to life.”

The Vault is a place where people tap into their innovative sides. “A recording studio is a magical place to be,” McCutcheon says. “There’s a feeling you get seeing a project come to life. It’s rewarding. Musicians know it. They don’t often have time to spend in a studio, so when they do, they make the most of it.”

Watch this VESTED Voices video featuring Bob McCutcheon to learn how a a corporate leader turned recording studio owner.

A Long Time Coming

Many of McCutcheon’s life experiences laid the groundwork for where he is today.

As a child, he pretended to be Glenn Campbell while strumming a toy guitar. In high school, he got a real guitar and played classic rock music in a band. He worked his way through college recording other artists’ music in his first recording facility, Alternative Studios, which he built in his mom’s garage.

Although he didn’t have formal training, he learned by trial and error. “A lot of it was experimentation,” he says. “The beauty of the recording arts is, technically, it’s art, not science, but there is a lot of science behind the physics of sound. It’s experimentation. If it sounds good, it is good.”

In 1991, he graduated from Robert Morris University, near Pittsburgh, with a double-major bachelor’s degree in business and finance. He chose those subjects because he wanted to run his own recording studio.

But instead, he landed a job with PwC and worked his way up the corporate ladder, enjoying every rung. “I realized I had an interest and a talent for business, accounting, and consulting. It was something I enjoyed. It happened to be an opportunity that was presented to me, and I took it.”

A couple of years after graduation, he met and married his wife, Dana. After their two children—Ryan and Brett—came along, McCutcheon’s daily time with music started to wane. He couldn’t juggle it all. “My hobby became almost nonexistent,” he says.

He figured his musical aspirations had been a phase of his life that was going to fade. “I kept a lot of my gear, but my guitars were in the closet collecting dust.”

McCutcheon says his career fulfilled him, so he was comfortable letting music fall to the back burner. “The firm offered me the ability to change jobs every couple of years. I was never doing the same thing twice. I was always able to innovate and find new and interesting things to do.”

But when his boys started to show an interest in music, his passion was rekindled.

Bob and Dana’s younger son, Brett, began taking piano lessons at age four. Later, Brett took up the saxophone and drums, started writing and recording music, and created his own YouTube channel.

Ryan found a passion for drums. He was drum captain in his high school marching band and played in a rock band in college.

As a way to spend time with them, McCutcheon built a small studio in their home, and the family played and recorded music together.

In 2016, on a flight home from Europe, he was flipping through the in-flight movie choices and stumbled on a documentary about the history of Sound City Studios in California. “It brought everything back,” he says. “I got off the plane, and thought, I’m in a position where I can do this now. Why am I not doing it?”

This was his aha moment. Finally, the time was right to do what he had always wanted.

Because of his role at PwC, McCutcheon knew how to conduct in-depth studies of different companies. “To serve my clients, I had to understand their industries,” he says. “My approach to starting the studio was no different. I studied the industry to learn about it.”

Once he felt he’d done enough research, McCutcheon wrote a plan, purchased an old bank building on Neville Island near Pittsburgh, and hired a firm that specialized in designing high-end recording facilities.

“At the time, it was still a personal studio project,” he says. “I was going to do my own recording on the weekends and evenings, but I knew I wanted to build it to commercial studio standards.”

The McCutcheon family funded the studio themselves. It was a passion project for all of them. In 2016, construction was complete, and The Vault was born, taking its name from the old bank vault in the basement of the building.

But he was still working in his corporate roles. “I was as busy as I had ever been with the firm. But we enjoyed the studio on the weekends with bands that I knew and with the kids. We were having fun doing recordings.”

Then, tragedy struck.

Loss and Clarity

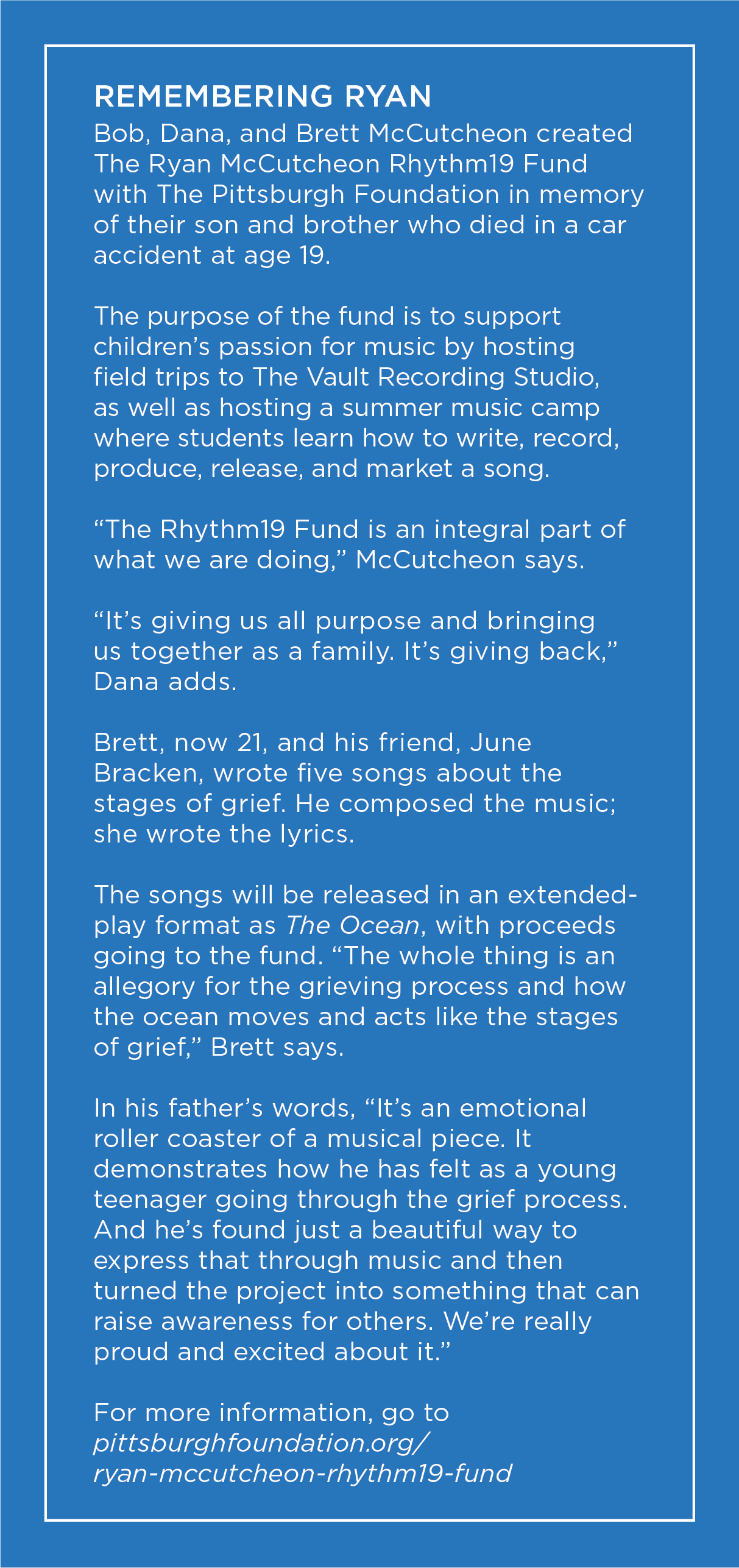

In September 2017, Ryan, 19, was killed in an automobile accident while returning to his college campus after a long day assisting high school drum students at a local band festival.

“The best we can tell is that he fell asleep at the wheel,” McCutcheon says. “Everything was turned upside down in a heartbeat. Everything just froze.”

McCutcheon took several months away from the firm. “I started to question what I wanted to do and what was important in life. It probably took me a year or so to assess where my heart was,” he says.

The loss changed him. “I just don’t look at things the same way I did prior to that. It was a defining moment. The things I value are very different now. You realize it’s about relationships. It’s about community. It’s about family.”

In December 2018, he retired, determined to spend more time with Dana and with Brett, who was still in high school. To cope with their loss, the McCutcheons found ways to give back to the community, often via music, with Ryan in mind.

The family established the Ryan McCutcheon Rhythm19 Fund with The Pittsburgh Foundation to support children’s love of music in a variety of ways. “We are keeping Ryan’s memory alive,” Dana says. “We mention Ryan’s name every day.”

Pumping Up the Volume

Trying to get back on track after the loss of their son was difficult. “We had just started The Vault label,” McCutcheon says. “It was hard to reenergize.”

He began expanding the studio beyond a small family affair to a world-class recording facility. Although Brett and Dana are still intricately involved in The Vault, McCutcheon also hired a roster of world-class producers and engineers.

One big step was the addition of Grammy Award-winning Jimmy Hoyson—who had previously worked with Michael Jackson, Eric Clapton, B.B. King, and other famous artists—as the studio’s chief engineer.

Hoyson told McCutcheon, “If you want to play big, you should find a Neve recording console.” And McCutcheon agreed. “Anybody who knows anything about vintage gear would love to get their hands on a Neve,” he says. “It offers such a warm, punchy vintage sound.”

They figured it would take 12 to 18 months to find one, but they hit the jackpot when, just a few weeks later, they discovered a restored Neve 8058. Later, they learned it once belonged to George Harrison of the Beatles.

McCutcheon’s goal for The Vault is to provide opportunities and services for those who are trying to make a living in the world of music. In the past five years, he estimates that hundreds of artists, many from Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia, have worked in the studio, including Chris Jamison, who finished third on NBC’s The Voice.

“When we first opened the studio, most days, I was the only one in the building,” McCutcheon says. “Now there are people walking in the halls every day.”

The Vault is drawing impressive professionals in sound engineering to build a powerful roster of producers. About half a dozen independent engineers and producers work out of the facility, as does McCutcheon, who also produces and engineers music.

Does he think The Vault has a chance to discover a breakout artist with a hit record? “That’s not why we do what we do,” McCutcheon says, “but it would be nice to have.”

“In the back of your mind, you hope it’s something that’s going to happen,” he says. “I’m surrounded by people who have had that happen multiple times. It just hasn’t happened from this building yet. But having these people here increases our odds.”

McCutcheon says he learned early in his career that successful people surround themselves with good teams, so that’s what he has done at The Vault.

Financially, the studio is self-sustaining, he says. “But I’m not getting rich doing this, and I’m not using this to support my family, which it was never intended to do. Even when it is making money, I’m putting that money back into the business. I’m funding my passion.”

Continuing to Grow

The McCutcheons recently renovated a second property, an old gas station across the street, to use as a multipurpose facility for charitable events, plus camps and other activities for students who want to learn about the music industry.

McCutcheon says he hasn’t had any doubts about his decision to open The Vault. “One of the things that I’ve learned throughout my career, and to be honest, solidified in my mind after the passing of my son, is that your passions define the core of who you are.”

“I feel fortunate that I had a clear understanding of what my passion was,” he says. “Then, I had a life event that made me slam on the brakes and question what I was going to pursue. I decided I was going to pursue what I was passionate about.”

“I wouldn’t say that my journey went according to plan,” he says. “But it’s ironic that things have completely turned around, and here I am after my retirement, still doing what I originally wanted to do.”

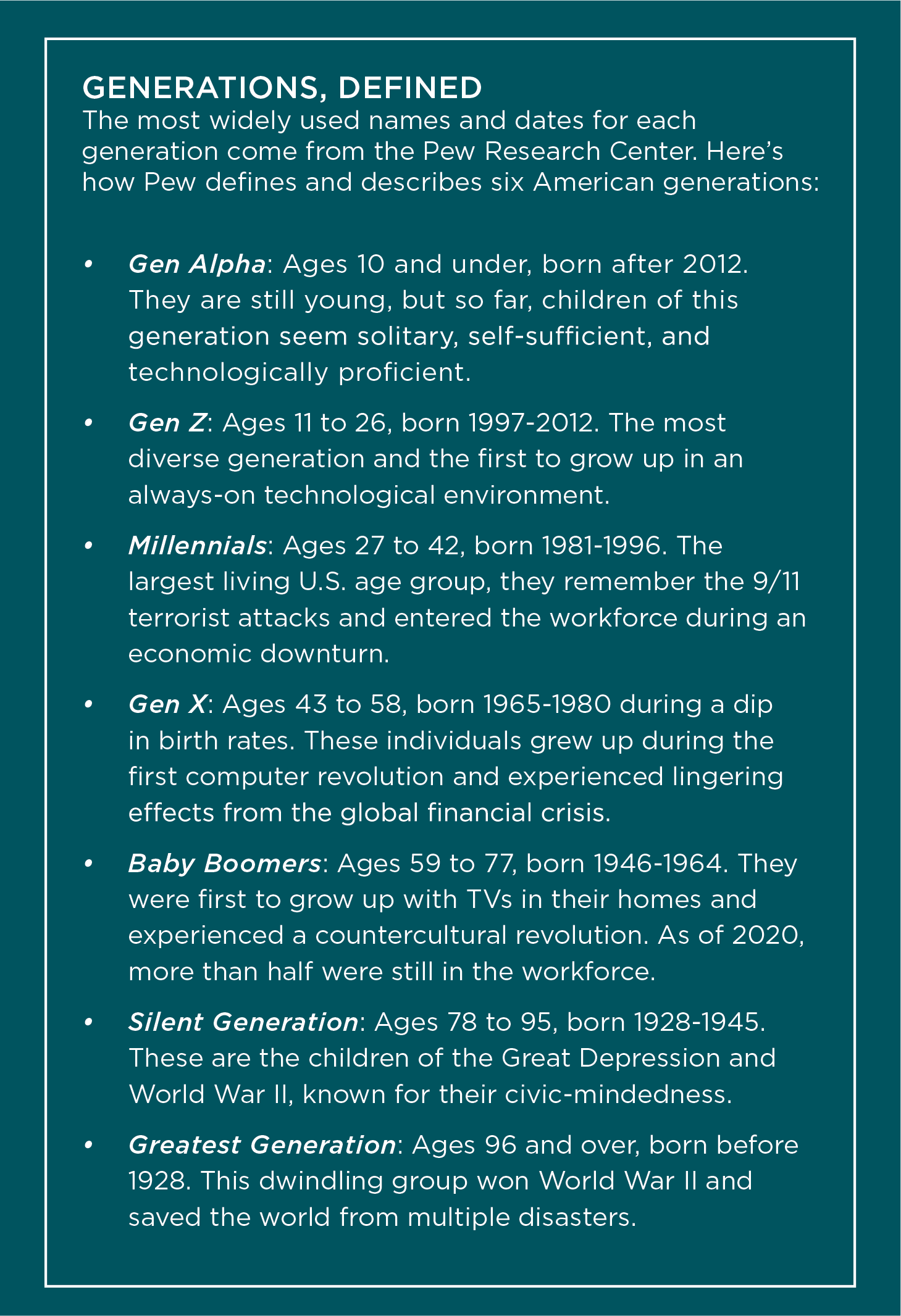

Research suggests Reeg is on to something. Older adults who build meaningful bonds with younger people, whether in their families, workplaces, or communities, live longer and happier lives. In fact, one long-running Harvard study recently found that social connection is the strongest predictor of well-being as we age. Bonds with younger people are particularly powerful happiness boosters, the research shows.

“Connection of any kind counters loneliness, which is especially common among youth and older adults,” says Kasley Killam, founder and executive director of the nonprofit Social Health Labs. Loneliness in older adults is linked with dementia, heart disease, and premature death, according to the National Institute on Aging.

Connecting with younger people is “a chance to be in touch with where the world is going” and to feel a greater sense of purpose in that world, says Katharine Esty, an 88-year-old psychologist and author of the book Eightysomethings. But to bridge the gaps, it helps to understand more about who is on the other side.

Beyond Bashing

Baby boomers were once viewed as being too revolutionary. Gen Xers were slackers. Millennials were entitled. And today’s young adults, members of Gen Z, are often branded as overly sensitive snowflakes, writes Megan Gerhardt and her colleagues in their recent book Gentelligence: The Revolutionary Approach to Leading an Intergenerational Workforce.

A few years ago, Gen Zers hit back with the “OK, boomer” retort to dismiss “older people who just don’t get it,” The New York Times reported. Gerhardt, also a Miami University business professor, says this type of generation bashing is downright unproductive, pushing people farther apart instead of helping them find a middle ground.

But understanding how each generation is different and unique can help people build stronger social ties, says Roberta Katz, a senior research scholar at Stanford University and co-author of Gen Z, Explained: The Art of Living in a Digital Age. The book is based on interviews, surveys, focus groups, and social media posts from teens and young adults born after the mid-1990s.

The young people who Katz and her colleagues spoke with when writing the book pushed back on the idea that they are fragile, coddled, and unable to deal with the world beyond their phones, she says.

Everyone who is alive today is experiencing the same technological and social upheaval, says Katz. “The difference is that’s the only world Gen Z knows. And we don’t know what the world looks like from their vantage point. We assume we do because we were young once, but we don’t really know.”

People born into Gen Z—that is, between 1997 and 2012—are “burdened by what feel like existential threats to their future,” such as climate change and school shootings, Katz says. They are wary of authority and hierarchy, something their schools and employers are grappling with. But, she says, they are eager to work collaboratively to solve the world’s problems.

They also are less glum than generally thought, says Sophia Pink, a 26-year-old doctoral student at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business. As an undergraduate at Stanford, Pink spent a summer interviewing fellow 21-year-olds around the country and learned that “they were pretty optimistic about their own lives and their own plans,” even as they despaired for the wider world.

It is true, Katz says, that younger people spend a lot of time on their phones. They can be impatient when older people don’t understand or follow their digital ways—for example, when their parents or grandparents send emails and leave voicemails although a simple text would do. But, she says, they do crave meaningful connections with others, including older people in their lives.

Reeg says she’s learned exactly that by spending time with her grandchildren. “If I have one of my grandkids in the car with me, and they’re looking at their phone while I’m talking, I just want to scream, take the phone, and throw it out the window. But I’ve learned that they can multitask better than we ever could. And actually, they are listening.”

There’s some truth to the idea that younger and older people “live in different worlds” and “speak different languages,” says Esty. Misunderstandings and hurt feelings can go both ways, she says. “Older people can feel ignored and not taken seriously,” just as younger people can.

But overcoming these barriers is worth it.

Photo above: Christeen Reeg and her grandchildren

“Older adults have wisdom and experience,” Killam says. “The younger generation brings a fresh perspective.” And connecting across generational divides can bring a greater sense of happiness and purpose for people of all generations.

Jumping the Chasm

Sometimes, bridging generational gaps can be particularly challenging. For example, consider a family in which grandparents and young adults have become estranged from each other for any number of reasons. In these cases, it’s important to remember that big emotions tend to fade over time and that past hurts can be easier to resolve than most people expect.

The more common problem, Esty says, is that “people don’t make the effort.” Since the first steps are usually the hardest, it helps to make them small.

That might mean doing what many older people did for the first time during the pandemic: using Zoom and FaceTime to meet up virtually with family, friends, and colleagues. People were craving human connections and leaping over technological divides to make them, social scientists say.

Older adults who now play online video games, use apps to watch movies with faraway friends, or swap daily Wordle scores with their children and grandchildren have made similar leaps. So have those who’ve become avid texters—even if they do use more punctuation and fewer emojis than their younger contacts would prefer.

Reeg says she tries to text each of her grandchildren at least once a week. “I’ll go through pictures, and I’ll see a memory picture, and I’ll just send it and say, ‘Thinking of you.’”

But older adults should not feel obligated to use digital technologies they don’t like. “Be true to yourself, and if you hate it, then don’t do it,” Esty says.

Pink says younger adults do understand that not everyone wants to use text or video chat. That’s why she calls her own grandparents on their landline.

Likewise, older workers don’t have to adopt all the technological tricks and habits of their younger colleagues, says Marci Alboher, a vice president at CoGenerate, a group that focuses on bringing multiple generations together to do good work. But, she says, everyone benefits when they can share favorite tools, like Zoom, Google Meet, or WhatsApp.

Beyond Tech Tools

Alboher says it’s wrong to assume that all younger people prefer texts and instant messages or that all older people prefer emails and phone calls. It’s better, she says, to ask. “If you are starting to work with someone or you’re joining a team, you can have a conversation about norms and preferences. You may expose yourself to some new communication styles, and you may find that people are suddenly more responsive to you.”

But don’t discount the value of a good in-person conversation. Katz says, in her research, one revelation was that young people valued in-person interactions above all others. “They are very much about human connection,” she says. “They want to be seen, and they want to be heard, just like everyone else.”

When you have those conversations, she says, be sure to listen, not just talk. “Don’t be judgmental. Ask them about their lives.”

Sometimes, connecting with younger people means “stepping out of your own comfort zone” and getting past the way they are “dressed or groomed or adorned,” says Lauren Lambert, a CAPTRUST financial advisor based in Boston, Massachusetts, who has advised multigenerational households, mentored younger colleagues, and raised two millennial children. “It’s important to respect them and their struggles. You really have to listen to them and remember what it was like to be their age.”

In the mid-1990s, after a string of product failures, Apple teetered on the brink of bankruptcy. But in 1997, one of the company’s founders—the legendary Steve Jobs, who had been ousted a decade earlier because of internal conflict—returned to the company and launched what has become an almost unbelievable story of resurgence.

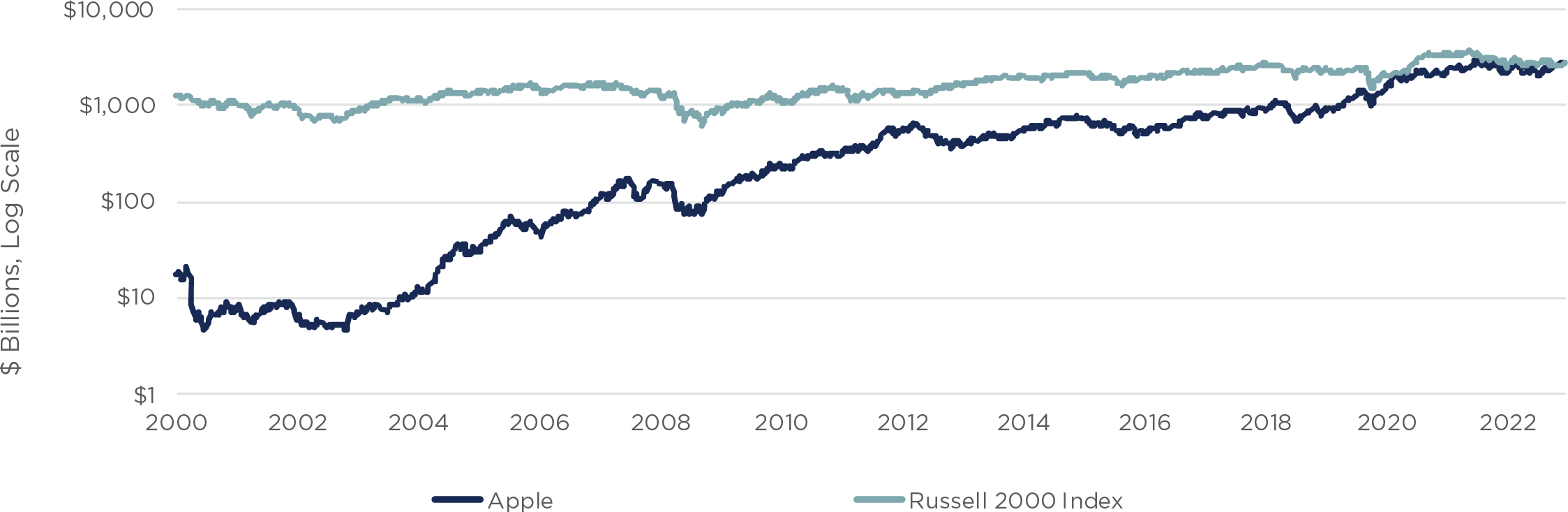

As shown in Figure One, the investment result has been astounding. Over the past 23 years, the market capitalization of Apple alone has eclipsed that of the entire Russell 2000 Index. To wrap your head around the size of this rebound, consider this: $1,000 invested on the day before Steve Jobs’s return as interim CEO in 1997 would now be worth more than $1,000,000.

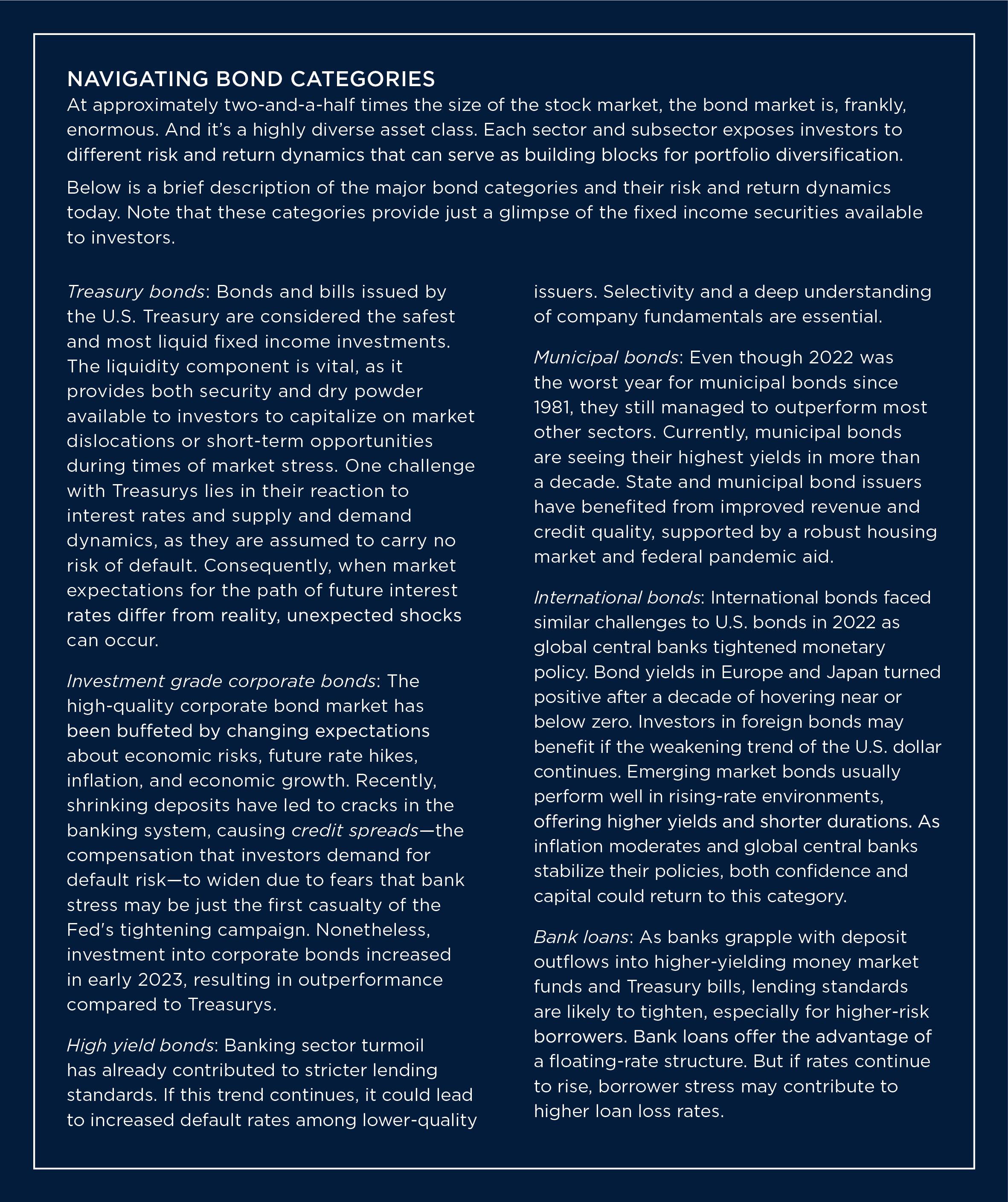

Fast forward to 2023, and it’s not just one company or security that is standing on the brink of revival. Rather, it is broad swaths of the largest and most liquid investment asset class: the bond market.

Figure One: Apple’s Market Capitalization vs. the Russell 2000 Index

Sources: Bloomberg, CAPTRUST

The Bond Market Slump

Following the first back-to-back negative annual returns for core bonds since the inception of the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index in 1976, conditions now seem ripe for a rebound. Core bonds are experiencing positive returns so far this year. But even more promising is the view that today’s significantly higher yields, coupled with the added potential for price appreciation, have increased the prospects for future returns more than at any other time in recent history.

Several factors weighed on markets last year, including an inflation shock and the Federal Reserve’s aggressive policy response. Inflation plays a major role in the bond market because it erodes the purchasing power of fixed income payments and can drive real yields—that is, the income from bonds after adjusting for inflation—into negative territory.

To fight inflation in 2022, the Fed acted forcefully, raising the fed funds rate a total of seven times, from 0 percent to 4.25 percent. This was followed by three more hikes in the first half of 2023, bringing the rate to 5 percent, with the potential for further increases.

While stocks were impacted in this rising-rate environment, it was bond investors who were most surprised by the setback. Core U.S. investment grade bonds, for instance, suffered a 13 percent loss, their worst return since the inception of the Barclays index.

Here, it is important to note that bonds offer two distinct sources of return: coupon payments and the potential for price appreciation. While coupon payments represent a steady source of income until a bond matures—assuming the issuer does not default—the price of a bond adjusts continuously based on prevailing interest rates.

For an investor who holds a bond to maturity, these price fluctuations are irrelevant. However, they’re an important piece of understanding the total return of a bond.

The Opportunity

Compared to the past decade, when yields were exceptionally low, the income generated by bonds now provides a more substantial cushion to counterbalance price declines caused by rising rates. Today, intermediate investment grade corporate bonds yield approximately 5.5 percent, up from 2.4 percent at the end of 2019.

This means that even if interest rates continue to rise gradually, bond yields have a much better chance to offset price declines, making a repeat of steep 2022 losses less likely in the near term.

Additionally, the current rate environment has improved the risk-reward trade-off for bonds compared to stocks. When corporate bond yields were below 3 percent, as was the case for most of the 2010s, even conservative investors seeking income had to explore alternative options. This led to a phenomenon known as there is no alternative (TINA), prompting many people to invest in stocks. However, with bonds now offering robust yields that exceed inflation, the mantra has shifted to there is now an attractive alternative, or TINAA.

The takeaway: Despite continuing economic uncertainty, bonds may now represent a more compelling opportunity than they have in years.

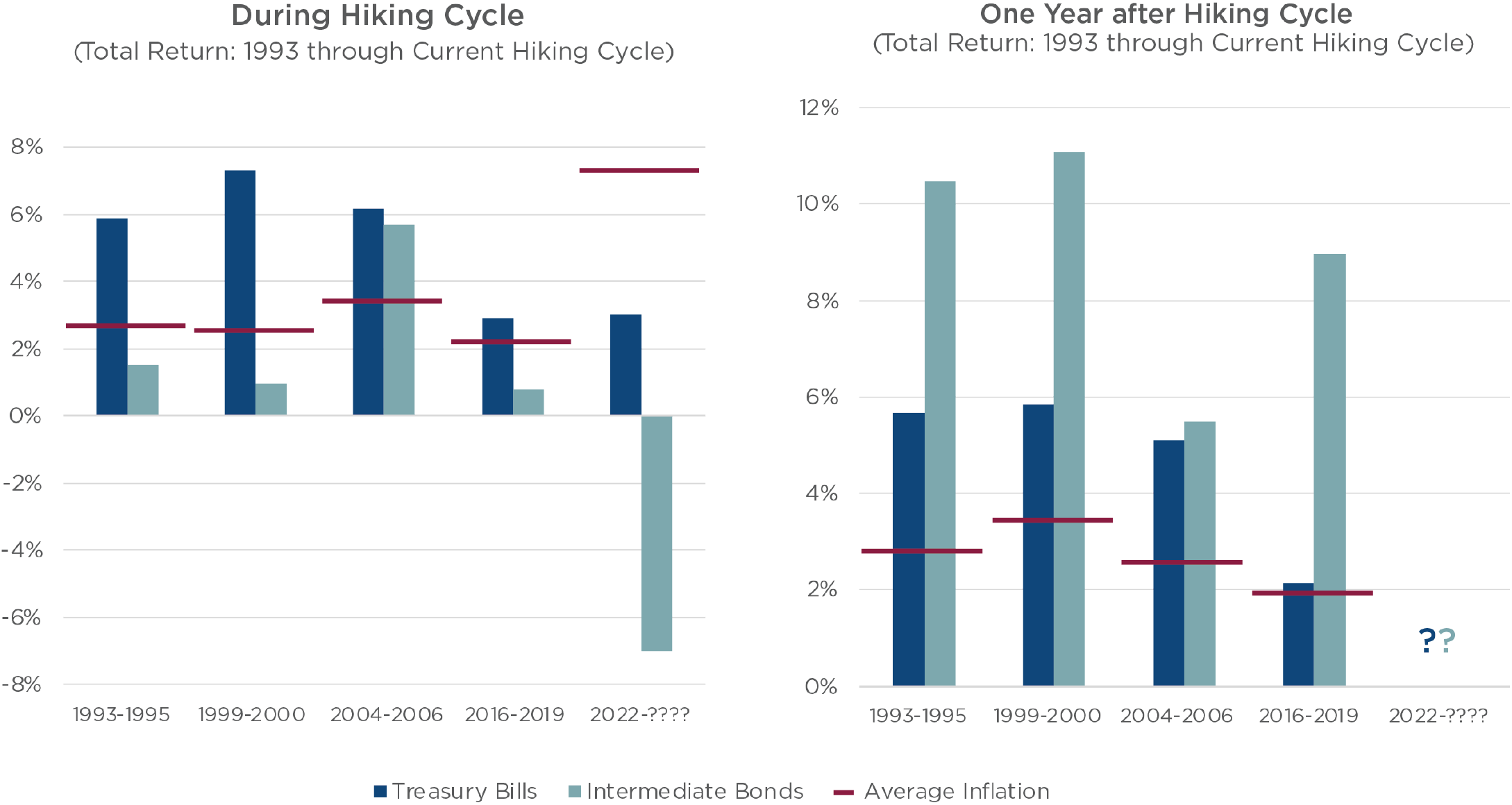

Figure Two: Treasury Total Returns during and after Hiking Cycles

Sources: Bloomberg, CAPTRUST

Bonds and Fed Tightening Cycles

The rate-hiking cycle that began in March 2022 represents the fastest and most aggressive move by the Fed since 1981. However, a significant distinction exists between now and then. While the fed funds rate was 16 percent at the start of the 1980s hiking cycle, it began 2022 at 0 percent. Essentially, the Fed’s tightening policy has begun to normalize interest rates amid its ongoing battle against inflation. This process of normalization has created a wide range of scenarios that could benefit bond investors through both higher yields and greater potential for price appreciation.

Recently, investors have grown anxious that higher rates, among other economic challenges, will push the U.S. into a recession. When anxiety grows about the state of the economy, investors tend to seek safe-haven investments and often flock to Treasury bonds. Higher demand for Treasurys drives their yields lower but their prices higher—a pattern that has repeated itself across previous hiking cycles.

As shown in Figure Two, bond returns are typically subdued during hiking cycles, with short-term bonds and Treasury bills outperforming longer-maturity bonds because they can be swiftly reinvested in the rising-rate environment. The left chart illustrates the combination of low initial yields and aggressive rate hikes. Since 2022, intermediate-term U.S. Treasury bonds have lost nearly 7 percent, while short-term (1 to 3 month) Treasury bills have shown positive returns of 3 percent. Adding to investor pain is the elevated level of inflation, represented by the red horizontal lines. This dynamic could compel investors to concentrate their bond investments in shorter-term securities like Treasury bills or even money market funds.

However, history shows a significant shift once the Fed’s hiking cycle is over. The right chart illustrates this trend. When the Fed maintains steady rates or begins cutting rates, it can trigger a bond rally that benefits longer-duration bonds, resulting in substantial price increases for those bonds.

Strategies for Investors

With money market funds now yielding 5 percent, investors may be tempted to load up on short-duration bonds to take advantage of these high yields with little or no price risk. This is particularly true given the current inverted yield curve, a relatively uncommon phenomenon when shorter-maturity bonds provide higher yields than bonds with longer maturities.

However, as with any investment strategy, there are risks in overconcentrating on any single type of investment, even safe, short-term Treasurys. Specifically, such investors face reinvestment risk—the risk that when a bond matures, interest rates may be lower than when it was bought, forcing the investor to reinvest at a lower yield.

There are three primary strategies bond investors can use to take advantage of attractive short-term yields while constructing a durable portfolio that is well-positioned for a range of potential future environments.

- A barbell is a tactical strategy that pairs bonds at different ends of the maturity curve—that is, both short- and long-term bonds. A barbell strategy represents a compromise, providing investors with the benefits of low-risk, higher-yielding short-term securities plus the lower reinvestment risk of longer-term bonds. If recession fears rise and investors rush to safe-haven assets, such as 10-year Treasurys, the barbell strategy could provide an effective hedge against risk.

- A bond ladder is a portfolio of bonds with staggered maturities. This serves to mitigate reinvestment risk and smooth out yield fluctuations. As bonds mature, the cash returned can be reinvested at the end of the ladder, allowing the investor to benefit if rates have risen. But even if rates have fallen, the investor can still benefit from earlier rungs on the ladder that retain higher yields. In addition, bond ladders can be structured to generate a consistent monthly income stream.

- Sector diversification across different bond categories is another way to enhance portfolio resiliency and tap into the potential for attractive risk-adjusted returns. However, navigating some corners of the fixed income market can be challenging due to nuanced risks and often hard-to-access information. Institutional-quality active managers with specialized expertise and resources may represent the best way to access these more specialized sectors.

As interest rates normalize from artificially low levels, the bond market seems well-positioned for a triumphant return. However, this does not mean investors can simply choose a bond strategy and then set it and forget it.

A wide range of dynamics will influence the fixed income landscape in 2023 and beyond. A prudent approach to the new bond market means intentional diversification in terms of maturity, sector allocation, and management style that matches investors’ risk tolerance and time horizon. Fortunately, the enormous size and robust diversity of the bond market provides a variety of securities that can be employed to create a diversified strategy.

Investment success is rarely achieved by chasing opportunities and avoiding challenges. Instead, it requires creating a financial plan and a resilient portfolio prescribed by that plan to transform setbacks into opportunities.

Catching the Comeback

Today, most people view Apple as a rousing success—both as an investment and as an innovator. But this doesn’t mean the business has not suffered its share of setbacks. For instance, consider the Newton, the Lisa, and the Pippin: devices that each presented a litany of faults, or perhaps ideas that were simply ahead of their time.

Yet companies, like people, should not be defined solely by their setbacks. And neither should investments. Many of us are familiar with the standard legal disclaimer used in investment advertisements: Past success does not guarantee future results. But the opposite is true as well. Past failures are not certain to be repeated.

According to a savings.com survey, 45 percent of parents with adult children provide financial support for at least one child, regardless of whether the child lives at home. Many of these parents are making significant sacrifices to help their children. They’re buying investment properties for their kids to rent at prices below market rates, withdrawing money from savings accounts to cover unexpected bills, and sending monthly allowances to help repay student loans.

The danger for some parents is that as their bank accounts dwindle, so do their chances of a secure retirement. In fact, the same study found that parents who are in the final decade before retirement are now providing the highest amount to their children—about $2,100 a month. The result: They’re depositing only $643 a month into their retirement accounts.

“As financial advisors—and fellow parents—it’s not our job to judge people for the way they spend their money,” says Joe Scarpo, a CAPTRUST financial advisor in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. “After all, it feels good to be able to provide for your kids. But if parents are risking their own financial health, it’s time to have an honest conversation.”

When Scarpo sees a client making poor financial decisions to support an adult child, “I try to explain to them, ‘It’s your choice if you want to continue allowing this. Just remember that if you go broke, then your kids will go broke too, because you’re helping them live a lifestyle they can’t really afford.’”

Breaking the Habit