Prioritizing Retirement Savings

First Step

Start saving through your 401(k) or similar retirement plans at work. Such plans typically let you save conveniently and automatically through payroll deduction, and they offer certain tax advantages to encourage your participation.

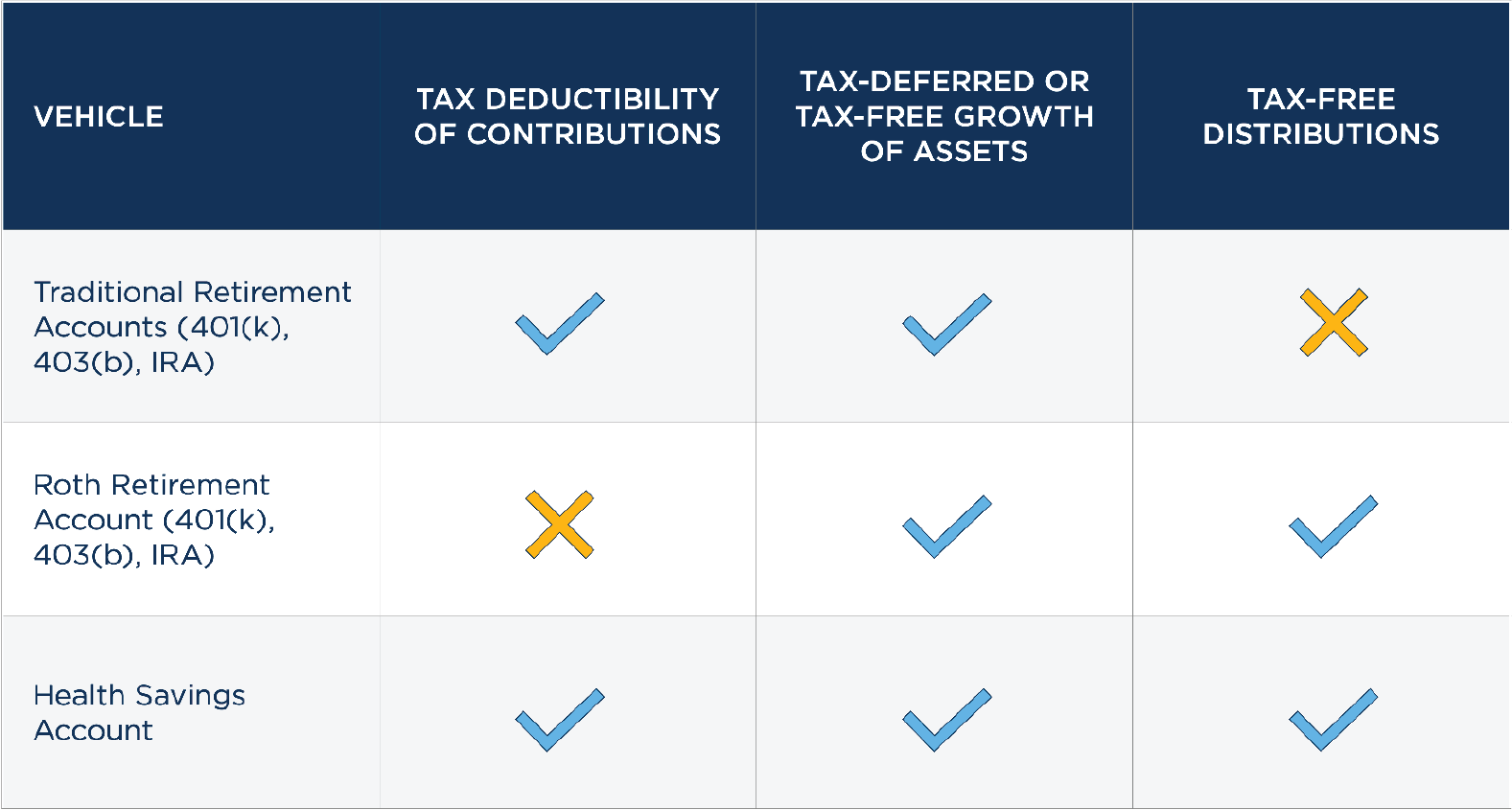

Figure One shows a breakdown of the tax advantages that apply to 401(k) plans as well as the other retirement savings vehicles mentioned in this article.

Figure One: Tax Preferences of Common Savings Vehicles

Note that assumptions and conditions apply. Please consult your tax and financial advisors about your specific circumstances.

Start saving as soon as possible. “The first dollars you save for retirement are the most productive,” says CAPTRUST Financial Advisor Steve Morton, a wealth management advisor based in Greensboro, North Carolina. This is because you have the maximum amount of time for those dollars to grow.

An added bonus: Your employer may encourage you to save by offering to match your contributions. “That’s free money,” Morton says, so be sure to take advantage.

Consider the following example.

Suppose that your gross annual pay at work is $100,000, and your employer has a retirement plan, such as a 401(k) plan or a 403(b) plan. Suppose, too, that your employer offers to match 50 cents for every dollar you contribute up to a maximum of 6 percent of your pay.

In that case, Morton says, if you kick in $6,000 to the plan in a given year, your employer will put in $3,000 as a match, for a combined total of $9,000.

That’s an immediate 50 percent return on your money, Morton says. “So don’t pass it up. Once you get into the groove of saving, you won’t miss it.”

There’s a cap on the total amount you can elect to set aside in your 401(k) plan, but the limit can increase each year with inflation, says Patricia A. Thompson, former chair of the Tax Executive Committee of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants.

For 2024, for people under age 50, the total employee pre-tax contribution limit is $23,000 and catch-up contributions for those over age 50 are limited to $7,500. Learn more about 2024 retirement plan contribution limits here: IRS Announces 2024 Retirement Plan Limitations.

Roth or Not?

Your employer may give you the option to save through a designated Roth account, Morton says. It’s technically a separate account in a 401(k) or similar plan to which designated Roth contributions are made.

The chief difference involves taxes. With a regular 401(k), contributions are made with pre-tax dollars, so you get an immediate tax deduction—a further incentive to save. Withdrawals, however, are subject to tax.

With a Roth account, contributions are made from your after-tax dollars, but withdrawals are typically tax-free. In other words, with a regular 401(k), the tax break is up front. With a Roth 401(k), it’s on the back end.

A Roth 401(k) can be “a very nice rainy-day savings account,” says Geoffrey T. Sanzenbacher, a research fellow at the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. “If your employer offers a traditional and a Roth option, you need not choose between them,” he says. “You can save in both.”

This move helps investors diversify retirement savings from a tax perspective, winding up at retirement with two pots of money from which to draw, one containing pre-tax dollars, the other after-tax money.

Which approach you take may also depend on where you stand in the savings cycle, Morton says.

For example, if you’re just starting out in the workplace, you may only be able to afford to save enough to qualify for the full matching amount from your employer. In that case, you may want to choose the traditional 401(k) account because it’ll give you the maximum up-front tax break. If you’re in your early 50s, however, you may want to put all of your retirement savings at work into the Roth 401(k) account. Of course, your specific tax situation should also be an important part of this analysis and may lead to a different conclusion, Morton says.

The HSA

Next in the retirement plan hierarchy is the health savings account, or HSA. Among its advantages:

- You can claim a federal income tax deduction for HSA contributions even if you use the standard deduction on your federal tax return (instead of itemizing deductions).

- Growth inside the account is sheltered from tax.

- Withdrawals (also known as distributions) are free of federal income tax if they are used to pay for certain medical expenses. The list is broad, from acupuncture and ambulance services to wheelchairs and X-rays. Physician, surgeon, and dentist services count too. And because of a change in federal law through the CARES Act, tax-free withdrawals can also be used to cover over-the-counter medicine (whether or not prescribed) and menstrual care products. Withdrawals for other purposes are subject to tax and possible penalty.

- An HSA is portable. It stays with you if you change employers or leave the workforce.

Your HSA can be a valuable savings tool with some flexibility, Morton says. One strategy is to use the amount in your account to pay for medical expenses for you and your family and let your remaining HSA balance grow by selecting an appropriate investment mix, shielded from tax, he says. Another strategy is to pay all your medical expenses out of pocket, letting the entire HSA account balance grow.

Keep in mind that HSAs aren’t for everyone. For one thing, you must have a high-deductible health insurance plan to accompany it. This means that your upfront and out of pocket costs may be higher than with other health insurance plans.

Back to Work

Once you’ve put enough in your 401(k) to qualify for the full employer match and you’ve stashed away money in an HSA, consider saving even more in your 401(k).

“I’d go the full boat,” Thompson says, because any additional amount you save, up to the annual maximum is done on a pre-tax basis, and your earnings grow on a tax-deferred basis.

Also, Thompson says, a 401(k) or other similar retirement savings plans is portable. Even if you change jobs, you typically have the option to transfer it directly to your new employer’s plan or to consolidate it in an individual retirement account (IRA) while your funds keep growing with no immediate tax consequences.

A 401(k) is not the only way to save, of course, and there are limits, too. If your plan allows for after-tax contributions, you may be able to save more.

Also, your employer’s plan may impose a lower limit on contributions than the law allows. If you are a manager, owner, or highly compensated employee, the plan might limit your contributions so that it passes certain required tests.

IRA Option

Another option is an IRA. With a traditional IRA, you may qualify for an income tax deduction for contributing, your account can grow on a tax-deferred basis, and your withdrawals are subject to income tax (and a penalty if you’re under 59 1/2, unless an exception applies).

With a Roth IRA, there is no upfront income tax deduction for contributing, your account can grow, shielded from tax, and withdrawals of contributions are tax-free. Withdrawals of earnings may escape federal income tax if you meet certain rules—generally, if you’ve held the account for at least five years and you’re 59 1/2 or older.

For 2024, the most you can contribute overall to a traditional or Roth IRA is $7,000 for those under 50, or $8,000 for those 50 and older.

However, a potential problem involves income limits.

If you seek a federal income tax deduction for contributing to a traditional IRA, your federal adjusted gross income (AGI) for 2024 generally must be below $68,000 if you’re single and $109,000 if you’re married and filing a joint return. If you do not have access to an employer plan, then there are different AGI limits that determine deductibility.

For Roth IRA contributions, your federal AGI for 2024 generally must be below $138,000 if you’re single and $218,000 if you’re married and file a joint return.

These limits may increase in future years with inflation, but you still may not qualify. That’s one reason why a retirement-savings plan at work may be your first and best option. In most cases, you can contribute no matter how high your income, and you may not be eligible to contribute to an IRA anyway, based on your income.

Backdoor Roth

To sidestep income limits on regular contributions to an IRA, you may be able to make a nondeductible contribution to a traditional IRA, Thompson says.

Although you can’t put in more in any given year than the overall contribution limit that applies to traditional and Roth IRAs, your ability to contribute won’t be restricted based on your income, she says.

Once you’ve made the contribution, you can promptly move the money from the nondeductible IRA to a Roth IRA—a technique known as a backdoor Roth IRA. Assuming you have no other IRAs, tax will be due at that point only on the earnings, if any, in your nondeductible IRA, Thompson says. If you have other IRAs, however, the tax consequences can be more complicated.

It’s important to note that pending tax law changes may affect some of the options we’ve described. For example, the House Ways and Means Committee has proposed new measures that would prohibit Roth conversions for individuals with taxable income of more than $400,000 and married couples with taxable income of more than $450,000 as of December 1, 2031. Despite the 10-year phaseout, the policy change could immediately affect financial planning for people who have complex estates and generational transfers.

More Options

Save in a taxable account. For example, put money directly into a mutual fund or brokerage account. You won’t get a federal tax deduction, but if you invest for growth alone, your account can grow tax efficiently. Taxes are typically due only when you cash out.

If your employer allows, set aside part of your pre-tax income at work through a nonqualified deferred compensation plan, Thompson says. Tax is deferred on your contributions and earnings. Withdrawals are taxable. But be careful: The money is considered part of the general assets of your employer, subject to creditors’ claims in bankruptcy.

Weigh whether to pay down any high-interest debt and then your home mortgage. “The [stock] market can go up, the market can go down, but you know what the rate is on your mortgage,” Thompson says, so you know what your rate of return will be in paying it down or paying it off.

While a retirement savings plan at work is “a great way to save for the long-term goal of retirement,” it can be “a terrible way to save” for other long-term goals, such as college savings, Morton says.

A key issue involves liquidity, Sanzenbacher says. In exchange for the many tax advantages of a 401(k) or other such plan, you typically have limited access to your funds (until retirement or certain other life changes).

If you do make withdrawals prior to retirement, you’ll not only face federal income tax (and state tax, depending on where you live), but also a 10 percent early withdrawal penalty (depending on your circumstances), he says.

While it can be hard to figure out where to put the money you save for retirement when there are multiple types of accounts you can open, the savings hierarchy can help retirement savers prioritize. By understanding where your money should go first, and then where any extra money should be funneled, you’re making a smart decision for your future.

Keep in mind that everyone’s situation is unique. While very few people ever regret saving too much for retirement, it is always a good idea to talk to your financial advisor about a personalized strategy for your retirement savings priorities.