General Liability Insurance Did Not Cover Retirement Plan Claim

Plan fiduciaries were sued for allegedly miscalculating the amount due to a profit-sharing-plan participant, and they submitted the claim to their insurance company. Although the insurance policy included a duty to defend by the insurance company, it refused to provide a defense. Litigation ensued, and the insurance company prevailed. Union Insurance Co. of Providence and Employers Mutual Casualty Co. v. Angus (D.R.I. 2025)

The insurance company was obligated to defend the plan fiduciaries, but only if the underlying claim was covered by the policy in force. Although the policy included an Employee Benefits Liability Coverage Endorsement, the court determined that the claim was not covered. Most policies include an exclusion for unpaid benefits to avoid shifting responsibility for an underpayment from the employer to the insurance company. This claim fell into that category. Importantly, the insurance policy also excluded all claims based on an alleged ERISA violation. The court observed that the claim was replete with ERISA-related allegations, bringing it within the ERISA exclusion.

This case is a good reminder that insurance policies covering general liability, errors and omissions (E&O), and directors and officers (D&O) do not typically cover ERISA claims. ERISA activities usually require a higher standard of care, so they are a different insurable risk. Typically, a separate policy or rider is required for coverage of potential ERISA violations. Department of Labor Support Continues for Plan Fiduciaries in Litigation Historically, the DOL could be relied on to support plaintiffs in their challenges to plan fiduciaries—or to be neutral. However, the DOL recently supported HP Inc. in its defense of challenges to the use of forfeitures with an amicus brief. Following this, the DOL asked the Supreme Court to hear an appeal in a case that would crystallize a stricter burden of proof standard in lawsuits against plan fiduciaries, making it more difficult for plaintiffs’ claims to prevail.

In Parker-Hannifin Corp. v. Johnson, the issue is whether the plaintiffs were required to allege underperformance relative to meaningful benchmarks to survive dismissal. The appeal is being brought to resolve a split in the circuit courts around the country, with some requiring meaningful benchmarks and others not.

The DOL also weighed in on a Supreme Court petition in Pizarro v. Home Depot, arguing in support of the employer that, when plaintiffs assert ERISA breach-of-fiduciary-duty claims, the burden of proof for causation should fall on the plaintiffs, not the defendant.

The DOL has also filed an amicus brief in the Konya v. Lockheed Martin (4th Cir. 2025) pension risk transfer case, supporting the actions of Lockheed Martin in the pension risk transfer transaction.

This is taking place against a backdrop of dramatically increased class-action litigation against plan fiduciaries. Many of the cases filed are dismissed or settled with small awards to plan participants—and significant payouts to the plaintiffs’ lawyers. Most of these cases that go to trial are decided in favor of the plan fiduciaries, after the investment of significant defense costs. Signaling likely continued activities in this vein, the DOL has decried regulation by litigation.

Cases Alleging Fee Overpayment and Investment Underperformance Continue: Process Wins

The flow of cases alleging that plan fiduciaries have overpaid for services and retained underperforming funds continues. In cases where details of the fiduciary’s process were evaluated, good fiduciary process prevailed.

Here are highlights from two of this quarter’s decisions.

- In its Cunningham v. Cornell ruling, the Supreme Court acknowledged it would now be easier for plaintiffs’ prohibited transaction claims to survive motions to dismiss, and in its opinion, the Court offered suggestions to lower courts about how to require plaintiffs to spell out their claims in more detail before the expensive process of discovery begins. The judge in Dalton v. Freeman (N.D. Cal. 2025) has followed that advice. We will be watching for the result.

- Prudential Insurance Company of America’s plan fiduciaries were sued alleging they failed to follow an adequate fiduciary process. The fiduciaries prevailed at the district court, and the dissatisfied plan participants appealed. Upholding the district court’s decision, the court of appeals noted the following:

- The duty of prudence is a process-driven obligation, so we must focus our inquiry on the fiduciary’s conduct in arriving at an investment decision and ask whether the fiduciary employed appropriate methods to investigate the merits of a particular investment at the time the fiduciary acted.

- Because this standard is flexible, we do not assess the prudence of a fiduciary against a uniform checklist.

- We focus on the fiduciary’s real-time decisions-making process and give due regard to the range of reasonable judgments a fiduciary may make based on her experience and expertise, and the difficult tradeoffs inherent in every investment decision.

- Seeking outside legal and financial expertise, holding meetings to ensure fiduciary oversight of the investment decision, and continuing to monitor and receive regular updates on the investment’s performance are hallmarks of a prudent investment process.

- Although the duty of prudence requires more than a pure heart and an empty head, courts have readily determined that fiduciaries who appropriately investigate the merits of an investment decision prior to acting easily clear this bar.

Cho v. The Prudential Insurance Company of America (3rd Cir. 2026).

- The Kellogg Company’s fiduciaries were sued alleging overpayment of recordkeeping fees. The case was dismissed. The court observed that the complaint against Kellogg did not include context-specific allegations comparing the plans and services received by Kellogg participants vs. those of the lower-cost comparators. The judge observed that, “Comparing apples and oranges is not a way to show that one is better or worse than the other.” Fleming v. Kellogg Company (W.D. Mich. 2025) (emphasis added).

Supreme Court Agrees to Hear Case Challenging Intel’s Investment Choices: Did the Plaintiffs Identify a Meaningful Benchmark?

The Supreme Court has agreed to hear the appeal of Anderson v. Intel Corp. Investment Policy Committee from the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. Intel was challenged for using hedge funds and private equity in their custom target-date funds. The lower courts found that the plaintiffs’ allegations failed to provide meaningful benchmarks for assessment of the funds’ performance.

Although some will focus on Intel’s use of hedge funds and private equity in a 401(k) plan, the issue the Court accepted regards what allegations a plaintiff must include in its complaint alleging breach of the duty of prudence for the selection and monitoring of a retirement plan’s

investments.

This is quite similar to the issue presented in Parker-Hannifin Corp. v. Johnson, where the issue of “meaningful benchmarks” also arises. The resolution of either Anderson v. Intel Corp. Investment Policy Committee or Parker-Hannifin Corp. v. Johnson provides the Supreme Court with an opportunity to weigh in on the pleading standards for claims in this area.

Cases Challenging Use of Plan Forfeitures Continue to Be Dismissed

Forfeitures occur when a plan participant leaves employment before the plan sponsor’s contributions to the participant’s account have vested. Lawsuits challenging 401(k) plan fiduciaries’ use of participant forfeitures to offset employer contributions—rather than to pay plan expenses that were eventually paid by plan participants—continue to be dismissed.

Perhaps advancing toward the end of a chapter on these types of allegations, the DOL has filed an additional amicus curiae brief supporting plan fiduciaries in Wright v. JPMorgan Chase & Co. (9th Cir 2025). The DOL has also indicated plans to file another in Barragan v. Honeywell International, Inc. (3rd Cir. 2025), also supporting the plan fiduciaries.

This quarter, several reported cases have followed what appears to be a consistent pattern of these claims being dismissed. Here are examples.

- Jacob v. RTX Corporation (E.D. Va. 1.22.26)—Dismissed

- Curtis v. Amazon.com Services, LLC 401(k) Committee (W.D. Wash. 1.16.26) —Dismissed

- Hernandez v. AT&T Services, Inc. (C.D. Cal. 11.14.25)—Dismissed

- Garner v. Northrop Grumman Corporation (E.D. Va. 12.4.25)—Dismissed

- Tillery v. WakeMed Health & Hospitals (E.D.N.C. 1.15.26)—Dismissed

- Brown v. PECO Foods, Inc. (S.D. Miss. 11.14.25)—Dismissed

- Polanco v. WPP Group USA, Inc. (S.D.N.Y. 10.27.25)—Dismissed

- Del Bosque v. Coca-Cola Southwest Beverages, LLC (N.D. Tex. 11.13.25)—Dismissed

- Donelson v. Meijer (W.D. Mich. 12.29.25)—Dismissed

New Front Opened in Fiduciary Challenges to Plan Sponsors: Supplemental Benefits

Many employers offer supplemental—sometimes called voluntary—benefits that are 100 percent employee paid. These often include supplemental insurance for hospital stays, cancer treatment, critical illness, and accidents. Plaintiffs’ lawyers who have led the way in filing class action suits challenging retirement plan fees and investments have recently set their sights on supplemental benefits. Four suits were filed in late 2025, alleging the following.

- Plan sponsors retained brokers without a diligence process and for unreasonable fees;

- There was not a thoughtful process to select or monitor the benefit providers or their fees; and

- Plan sponsors agreed to arrangements resulting in overpayment for supplemental

coverage.

The cases are:

- Brewer v. CHS/Community Health Systems, Inc. (N.D. Ill. complaint filed 12.23.25)

- Braham v. Laboratory Corp. of Am. Holdings (N.D. Ill. complaint filed 12.23.25)

- Fellows v. Universal Serv. of Am. (S.D.N.Y. complaint filed 12.23.25)

- Pimm v. United Airlines, Inc. (N.D. Ill. complaint filed 12.23.25)

These claims also name the brokers, including Gallagher Benefit Services, Inc., Mercer Health and Benefits Administration LLC, Lockton Companies LLC, and Willis Towers Watson U.S. LLC.

ERISA exempts some benefits from its requirements if:

- The employer does not make any contribution to the program;

- Participation is completely voluntary for employees;

- The employer’s sole function is to make the program available and serve as a conduit for premiums, with no employer endorsement; and

- The employer receives no direct or indirect compensation or consideration beyond payment for their direct costs of allowing the program.

These claims, plus others based on health and welfare benefits, underscore the need to have a thoughtful and diligent process for the selection and monitoring of service providers in these areas.

This material is intended to be informational only and does not constitute legal, accounting, or tax advice. Please consult the appropriate legal, accounting, or tax advisor if you require such advice. The opinions expressed in this report are subject to change without notice. This material has been prepared and is distributed solely for informational purposes. It may not apply to all investors or all situations and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. The information and statistics in this report are from sources believed to be reliable but are not guaranteed by CAPTRUST Financial Advisors to be accurate or complete. All publication rights reserved. None of the material in this publication may be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of CAPTRUST: 919.870.6822. ©2026 CAPTRUST Financial Advisors.

First, a little background around charitable deductions may be helpful. Charitable donations are below-the-line itemized deductions. This means they impact the tax formula after your adjusted gross income (AGI) has been calculated.

A below-the-line deduction does help lower your taxable income but would not impact your AGI. Because of where they sit in the tax formula, the ultimate impact of below-the-line deductions depends on your tax bracket.

The amount of a deduction that can be used in a single year is based on the type of charity, the asset donated, and the individual’s AGI. Unused deductions can be carried forward for up to five future tax years.

From a tax-planning standpoint, itemized deductions only benefit the individual taxpayer to the extent that they exceed the standard deduction for the year. All the itemized deductions for the year can be combined to exceed this threshold. Common itemized deductions are state and local taxes, mortgage interest, medical expenses, and charitable donations.

For example, in 2025, if a couple donated $25,000 to charity and has other itemized deductions of $15,000, their total itemized deductions would exceed the standard deduction. Therefore, they would get better tax benefits by itemizing, instead of claiming the standard deduction.

Instead of subtracting the standard deduction of $31,500 from their AGI to determine their taxable income, they would be able to subtract $40,000. This would ultimately end up lowering the taxes due.

New Charitable Deduction

A new charitable deduction is now available to those who are using the standard deduction. Direct cash donations to charity can now be deducted as an above-the-line deduction up to $1,000 for those who file as single and $2,000 for those who file married filing jointly.

This new deduction, unlike the traditional charitable deduction, is an above-the-line deduction, which means it would be subtracted before AGI is calculated. This provides a more substantial benefit as it would be a dollar-for-dollar reduction on taxes due. Lowering AGI provides additional benefits as AGI is used for phase-out ranges on other deductions and benefits.

Donations to a donor advised fund (DAF) or private non-operating foundation are excluded from this deduction. With the current standard deduction, more than 87 percent of filers take the standard deduction instead of itemizing, according to the IRS.

Charitable Deduction Floor and Cap

If you typically itemize deductions, charitable donations now have a floor before the deduction can be used. This floor is 0.5 percent of the individual’s AGI.

For example, in 2026, if the same couple donated $20,000 and has an AGI of $350,000, only the amount that exceeds the $1,750 floor would count toward their itemized deductions. If they had the same $12,000 in other itemized deductions, they would not benefit from itemizing in 2026 due to the impact of the charitable floor. This is because the $20,000 charitable gift plus the $12,000 additional deductions, minus the new charitable floor of $1,750, is less than the new $32,200 standard deduction.

The charitable floor has a more significant impact on higher-income donors as the floor is based on income. For example, an individual with an AGI of $500,000 would have a charitable floor of $2,500. The floor increases as AGI increases, providing a larger reduction in the amount of charitable donations that can be used as a deduction.

The new tax rules also create a cap on tax benefits for those who itemize charitable deductions at 35 percent, and for those in the 37 percent marginal tax bracket. Previously, an individual in the 37-percent bracket would be able to reduce their taxes due by 37 cents for every dollar of an itemized deduction. This new rule would cap that benefit at 35 cents for every dollar for these individuals, slightly muting the benefits for high income individuals.

Tax Strategy Considerations

Non-itemizers may want to consider how they make charitable donations and consider direct cash gifts up to the $1,000/$2,000 deduction, since this now provides a direct tax benefit that wasn’t previously available.

Donors who itemize may want to consider the timing and amounts of their giving. Leverage bunching to concentrate donations in years where you can maximize the donation available.

As always, it’s a good idea to consult your financial advisor. They can help you understand which strategies suit your unique financial goals.

Sources: “SOI Tax Stats Charities and Other Tax Exempt Organizations Statistics,” Internal Revenue Service, CAPTRUST research

Resource by the CAPTRUST wealth planning team.

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and does not constitute an offer, solicitation, or recommendation to sell or an offer to buy securities, investment products, or investment advisory services. Data contained herein from third-party providers is obtained from what are considered reliable sources. However, its accuracy, completeness, or reliability cannot be guaranteed. Nothing contained herein constitutes financial, legal, tax, or other advice. Consult your tax and legal professional for details on your situation. Investment advisory services offered by CapFinancial Partners, LLC (“CAPTRUST” or “CAPTRUST Financial Advisors”), an investment advisor registered under The Investment Advisers Act of 1940.

What’s happening: AI is becoming more visible across the nonprofit sector, prompting organizations to evaluate where it may support mission-driven work.

Why it matters: Foundations invested $300 million in AI initiatives from 2018 to 2023—with one-third focused on governance and ethics1—and 61 percent of nonprofits now use AI for fundraising and development tasks.1

What to know now: While AI is not essential for every nonprofit, understanding its potential applications can help leaders make thoughtful and strategic decisions about whether and how to explore it.

Potential Applications in Fundraising and Donor Engagement

What AI can do:

• Analyze donor engagement patterns

• Predict which supporters may give again

• Inform personalized outreach strategies

What the data shows:

• AI-enabled campaigns reached goals 33 percent faster due to better targeting and timing.2

• In one case, AI tools predicted donor renewal with 86 percent accuracy.2

• Recurring gifts rose up to 264 percent when organizations used AI supported personalization.4

The takeaway: AI can accelerate fundraising progress and stretch limited development capacity. However, it should not replace the real-world relationships that drive philanthropy. It can simply help direct staff attention where it can be most effective. AI tools may be useful where teams are stretched and data exists, but suitability depends on culture, strategy, and staff capacity to act on insights.

Streamlining Administrative and Operational Processes

AI may also help to ease administrative burden, freeing time for more mission-critical work.

Where AI helps:

• Organizing information

• Summarizing reports

• Supporting compliance documentation

• Reducing repetitive, time-consuming tasks

Real-world example: Houston Endowment’s AI-powered, oral reporting pilot cut grantee administrative time by 75 percent and improved feedback.3

How to evaluate fit:

• Identify bottlenecks or repetitive tasks

• Assess whether they are data-heavy or ripe for automation

• Consider alignment with operational goals and available capacity

Enhancing Program Analysis and Decision-Making

AI can enable rapid analysis of large data sets to identify trends, forecast needs, or assess risks. In one example, during the 2023 Sudan conflict, Mercy Corps used AI to analyze 10 years of satellite data, identify famine risk zones, and deploy aid preemptively.2

Important considerations:

• AI insights are only as reliable as the underlying data

• Staff expertise is essential for interpreting outputs

• Data governance and quality must be strong

Could it help your organization? Maybe. AI can strengthen data-driven decision-making, especially when timeliness matters, but its use requires solid data practices and analytical capacity.

Readiness, Training, and Ethical Considerations

Current state:

• 68 percent of nonprofits want staff training before adopting AI.1

• By late 2025, 73 percent had no AI policies in place.5

Why governance matters:

• Protects sensitive information

• Ensures alignment with organizational values

• Builds transparency and equity

• Addresses privacy, bias, and accountability concerns

In other words,AI readiness requires training, digital literacy, and responsible governance.

Planning Thoughtfully and Moving at the Right Pace

Remember: AI adoption isn’t all-or-nothing. Organizations can start small by identifying specific pain points or opportunities.

Potential questions to ask your team:

• Which activities regularly require significant manual effort?

• What insights would strengthen decision-making?

• What data governance structures exist—and what’s missing?

• How might AI complement (not replace) human relationships?

• What training or capacity building is needed for responsible use?

The punchline: A cautious, intentional approach to AI implementation allows organizations to evaluate benefits and risks without pressure. AI may offer meaningful support for some, but it should only be adopted when it advances the mission and strengthens the team.

Sources:

1“AI with Purpose: How Foundations and Nonprofits Are Thinking About and Using Artificial Intelligence,” The Center for Effective Philanthropy

2 “Machine Learning for Nonprofit Organizations.” Journal of Nonprofit Innovation

3 “Pilot Project Centers Grantee Voice through Oral Reporting and AI,” Houston Endowment

4 “How AI Can Deepen Nonprofit Relationships,” Stanford Social Innovation Review

5 “Grassroots and Non-Profit Perspectives on Generative AI,” Joseph Rowntree Foundation

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and does not constitute an offer, solicitation, or recommendation to sell or an offer to buy securities, investment products, or investment advisory services. Data contained herein from third-party providers is obtained from what are considered reliable sources. However, its accuracy, completeness, or reliability cannot be guaranteed. Nothing contained herein constitutes financial, legal, tax, or other advice. Consult your tax and legal professional for details on your situation. Investment advisory services offered by CapFinancial Partners, LLC (“CAPTRUST” or “CAPTRUST Financial Advisors”), an investment advisor registered under The Investment Advisers Act of 1940.

References to third‑party research or organizations are for informational purposes only and do not imply affiliation, sponsorship, or endorsement.

“Everywhere but in the Productivity Statistics”

In the late 1980s, the personal computer revolution was in full swing. Desktop computers were expected to reinvent workplaces through automation and faster decision-making. Adoption skyrocketed as PC prices fell and computing power soared.

In 1987, the year that Microsoft Windows version 2.0 added desktop icons to screens, about 25 percent of U.S. workers used a computer at work. This is roughly equal to estimated AI use in workplaces today.[1]

Yet that same year, Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Solow famously quipped, “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.”

The AI boom of the past three years has fueled one of the greatest wealth-creation engines ever, but the timing and extent of its payoffs are still uncertain. Meanwhile, significant inflationary forces remain in place, just as fiscal stimulus and, potentially, lower interest rates are poised to add fuel to the fire.

This creates a high-stakes footrace. Can the productivity gains promised by AI deliver the economic elixir of disinflationary growth, allowing inflation to settle without stalling the economy?

Market Rewind: Signs of Rotation

The first half of 2025 was defined by the narrow leadership of mega-cap AI stocks. In the fourth quarter, the rest of the market played catch-up.

Global markets ended the year on a decisive upswing, but the leaderboard changed as capital flowed toward broader, more cyclical sectors of the market.

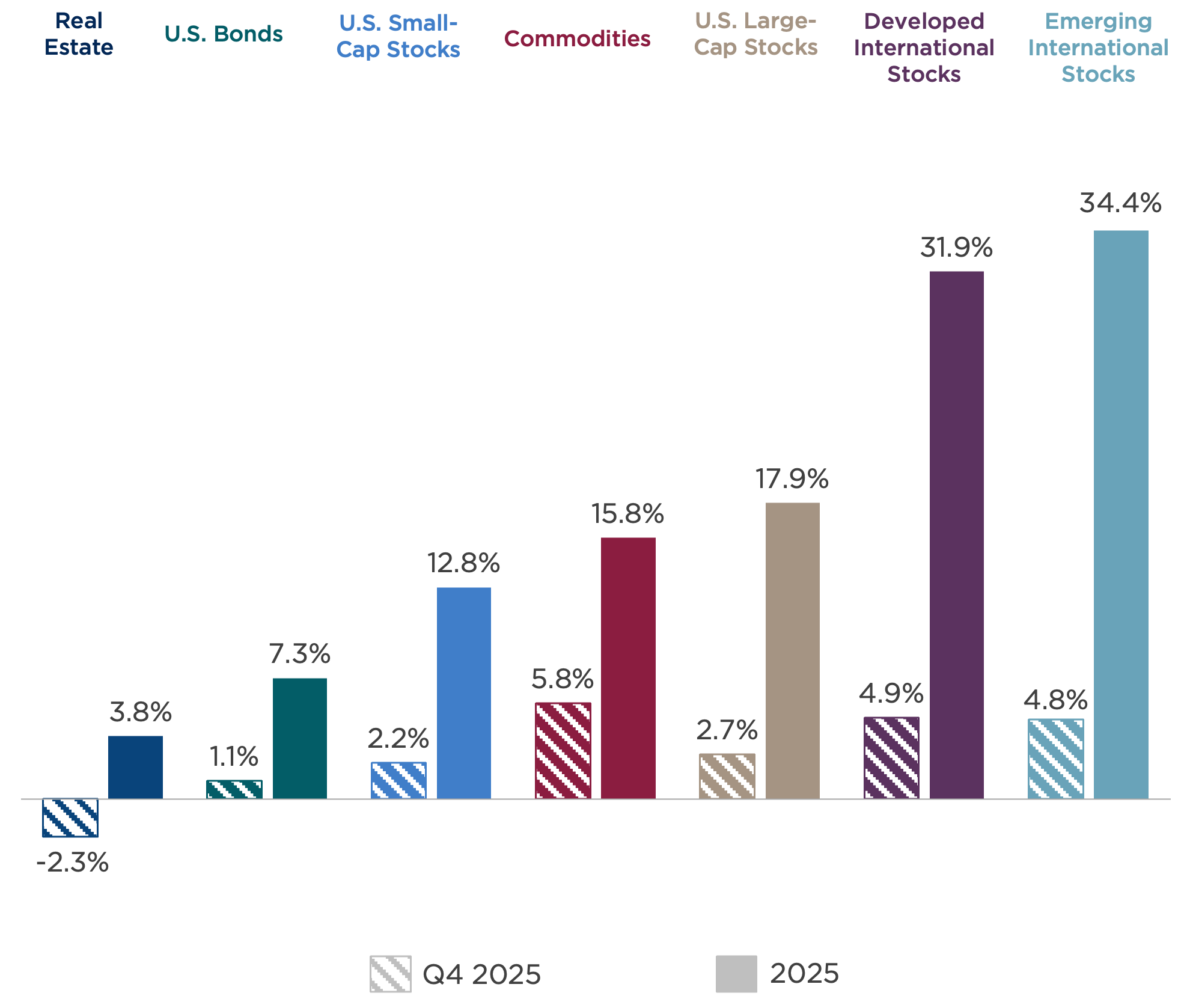

Figure One: Asset Class Returns, Q4 2025 and Full Year 2025

Asset class returns are represented by the following indexes: Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (U.S. bonds), S&P 500 Index (U.S. large-cap stocks), Russell 2000® (U.S. small-cap stocks), MSCI EAFE Index (international developed market stocks), MSCI Emerging Market Index (emerging market stocks), Dow Jones U.S. Real Estate Index (real estate), and Bloomberg Commodity Index (commodities).

International Markets Take the Lead

Developed and emerging international stocks each delivered nearly 5 percent returns in the fourth quarter, almost double that of the S&P 500 Index. Their outperformance was driven by a powerful trifecta: attractive valuations relative to high-priced U.S. stocks, a weakening U.S. dollar, and synchronized stimulus efforts abroad.

For the full year, emerging markets were the standout performer, gaining more than 34 percent, driven by strong performance from emerging Asian economies and the rise in precious and industrial metals prices, even as energy commodities lagged.

U.S. Stocks Broaden

The S&P 500 posted a modest 2.7 percent gain in the fourth quarter and a strong return of nearly 18 percent for the year. But market dynamics shifted considerably throughout 2025. The Magnificent Seven trade cooled as future earnings-growth expectations began to normalize, and more than a trillion dollars of S&P 500 market cap rotated away from the technology sector in November and December.

For the past three years, the largest tech stocks have carried the U.S. equity market on their backs, driving their price-to-earnings (P/E) multiples to elevated levels. The forward P/E multiple of the top ten S&P 500 stocks surpassed 28x at year-end—well above the full index (at 22x) and the long-term index average of 17x. At these levels, the Magnificent Seven stocks are priced for perfection.[2]

This valuation gap, plus growing optimism about the earnings-growth prospects of the broader index, helps explain the rotation we witnessed late last year. Solid economic growth conditions and upcoming stimulus promise to boost cyclical sectors. At the same time, expectations for lower interest rates and early AI-related productivity gains could improve profit margins in some corners of the markets that were largely left behind for the past three years.

Fixed Income Faces Yield Divergence

The bond market spent the fourth quarter caught in a tug-of-war between Federal Reserve rate cuts and growing fiscal anxieties.

Short-term bond yields fell after the Fed delivered its third rate cut of 2025, and the 10-year Treasury yield ticked higher as investors pondered the forward path of inflation. In the background, investors nurtured anxieties over federal debt and deficits.

This steepening of the yield curve limited gains for core bond investors, with the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index returning a muted 1 percent for the quarter.

Metals Move Commodities Higher

The diversified commodity index was the best performing asset class in the quarter, rising nearly 6 percent. A global manufacturing pickup boosted prices for industrial metals, but the biggest commodities return-driver continues to be the surge in precious metals.

Gold’s breakout performance, happening in tandem with strong equity returns and modest inflation, is a historical outlier. Typically, gold’s strongest returns occur when investors seek a hedge against rampant inflation, or when they lack confidence in traditional assets to produce returns. This break from the traditional stock-to-gold correlation may be a sign that investors now view gold as a hedge against not only inflation but also elevated—and seemingly accelerating—policy uncertainty.

Overall, the 2025 mosaic shows markets propelled by an AI spending theme but still uncertain of the theme’s sustainability. The global economy seems to be anticipating a jolt from fiscal and monetary stimulus but wary of the second-order effects of debt and deficits, inflation, and instability.

It’s a landscape of investors with many questions. And in their uncertainty, like high school students looking for help with homework, they’re turning to AI for answers.

AI and its Productivity Precursors

History offers a few examples of tech-driven efficiency capping inflation during times of high growth.

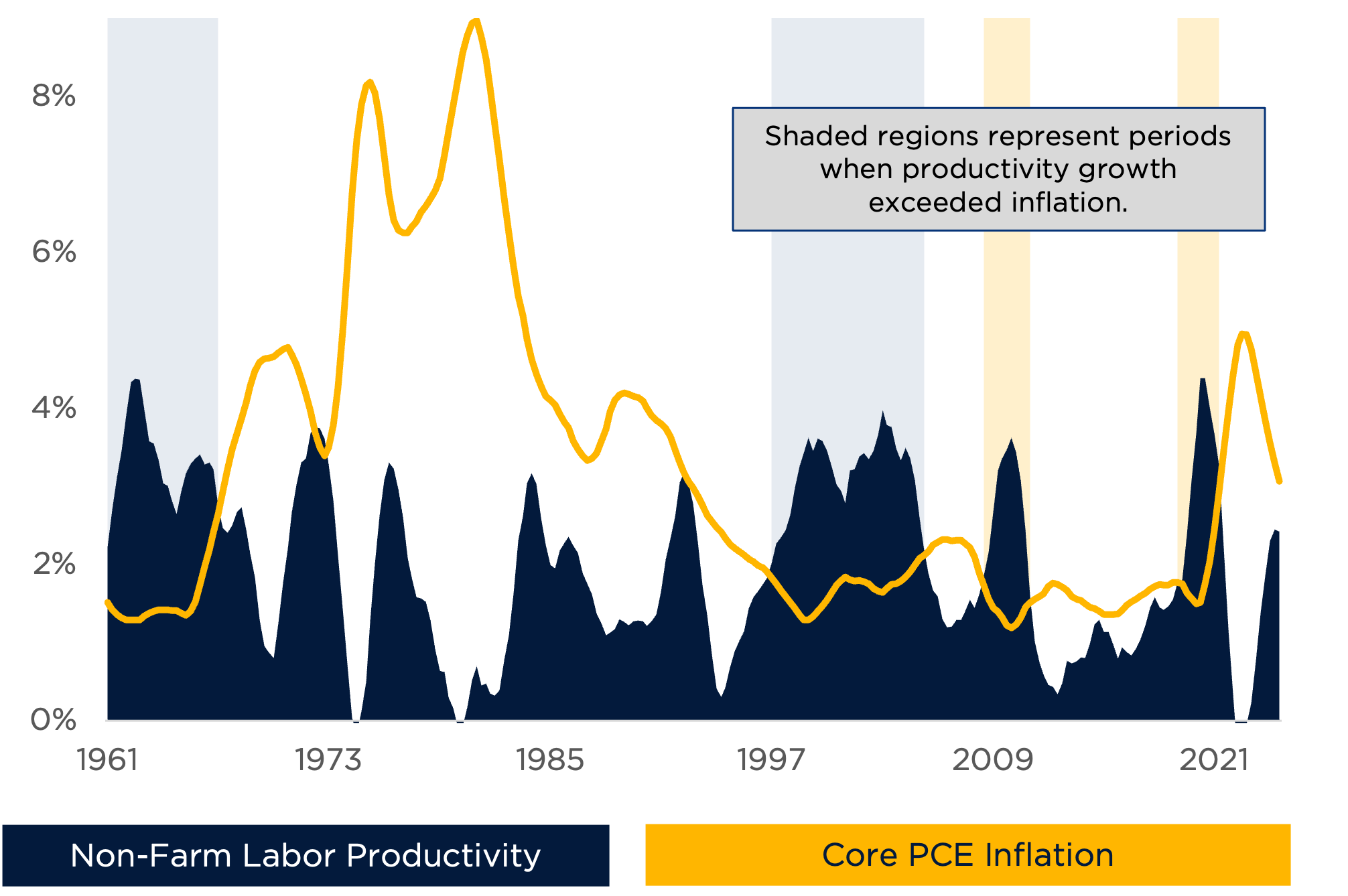

As shown in Figure Two, there have been four distinct periods over the past 65 years when the rate of productivity growth—that is, the amount of economic output per hour of labor— has exceeded the rate of inflation. Two of these periods (shaded gray) represent the factory automation wave of the 1960s and the digital revolution of the 1990s. In these eras, productivity grew because of increased output. The other two periods (shaded yellow) show times of productivity growth for the wrong reasons, such as a shrinking workforce in post-crisis recovery periods.

Figure Two: Labor Productivity and Core Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) Inflation

Year-over-year growth%, 8-quarter moving average

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, CAPTRUST research

In each of these periods, Americans were openly concerned about job losses, as is true today. In the 60s, workers feared the elimination of factory jobs. In the 90s, they felt anxious about an e-commerce-driven retail apocalypse. Today, the worry centers around white-collar knowledge workers in fields from software engineering to customer service, law, and investment banking.

Yet these episodes, plus many earlier examples, show that technology advances rarely trigger mass unemployment. Instead, they reduce costs and unlock new demand, supporting disinflationary growth.

And, importantly, tech-triggered productivity gains can materialize well before the maturity of the technology itself.

Real World Examples

Consider the U.S. auto industry in the 1960s. General Motors sought to automate its Lordstown plant with the first fleet of robot welders, but the project stalled because robots could not maneuver components into place (with crowbars and rubber mallets) the way skilled human assemblers could. The robots required components to have more precise tolerances.

GM responded by demanding higher standards from its stamping plants so that its robots could perform. But the ironic result was that these tighter tolerances made even its non-automated factories far more productive, with lower defect rates. It wasn’t just the technology that drove productivity gains. It was also the precursors to implementation.[3]

We saw the same phenomenon during the software boom of the 1990s. Businesses uncovered massive inefficiencies as they prepared to shift their enterprises to single-database platforms. One famous case involved Nestlé, which realized its factories were paying 29 different prices for vanilla from the same vendor because each factory coded the ingredient differently in its fragmented legacy systems. The simple act of factory leaders coming together to standardize the names of ingredients unlocked massive bargaining power, savings, and efficiency.[4]

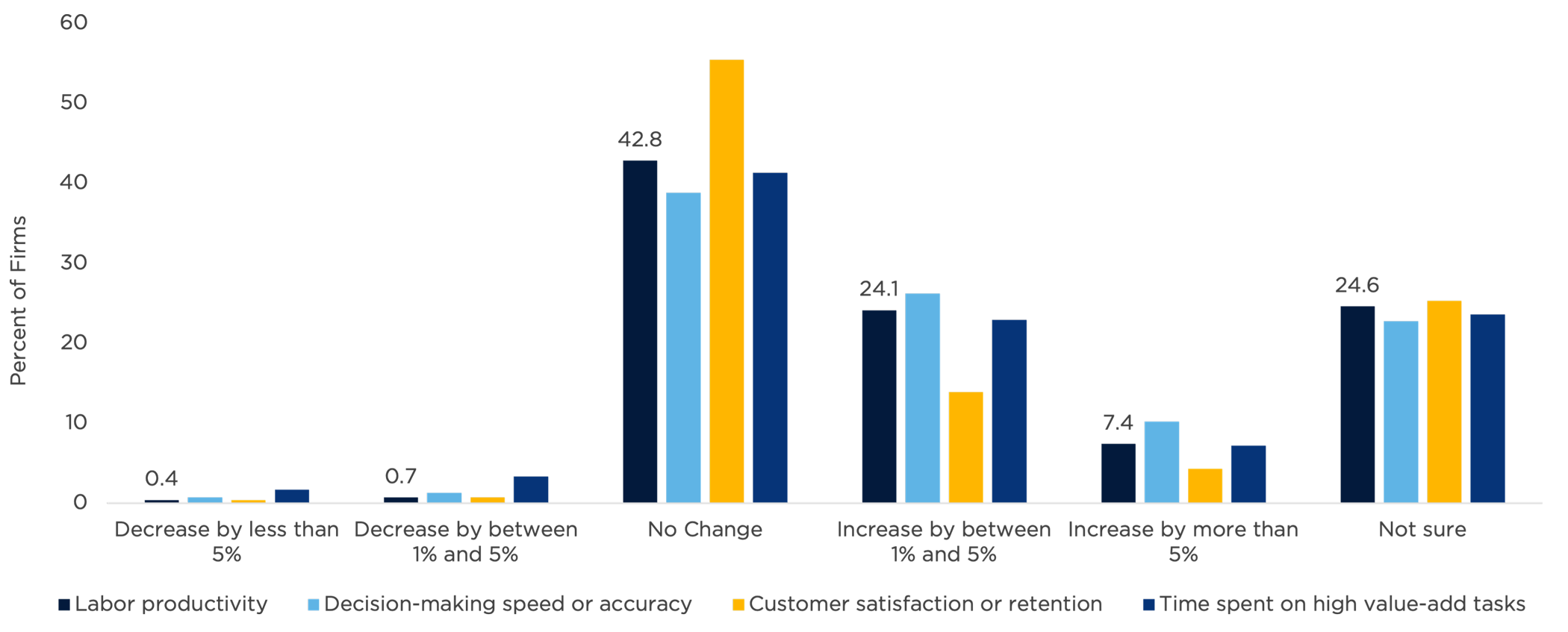

Today, executives anxiously await AI payoffs, but survey findings, shown in Figure Three, suggest early results are tepid at best.

Yet, if the past is prologue, the earliest gains may stem from the groundwork required for AI projects, instead of AI itself. Companies must clean and standardize their data. If a forgotten, three-year-old PDF buried in a directory contains bad information, then even the most finely tuned AI agent will deliver flawed results. But once the file is fixed, human customer-service reps also become faster and more efficient—well before the AI agents come online.

Figure Three: CFO Survey: How Has AI Affected Your Firm?

Source: “The CFO Survey – Q4 2025,” Duke University, FRB Richmond, and FRB Atlanta

2026 Outlook: Mark Your Calendars

2026 will be an eventful year of both routine happenings (like data releases and Fed meetings) and special events that will offer abundant chances for the emergence of winners and losers, whether on ski slopes, on football fields, in polling places, or in the financial markets.

Fiscal Fuel from the One Big Beautiful Bill

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) sets the stage for a major injection of stimulus this year. As we head into tax season, tax code changes could release a firehose of cash to consumers, including:

- Adjustments to tax brackets;

- A child tax credit expansion;

- New deductions for people over 60; and

- The elimination of tax on overtime pay and tips.

These changes could lead to an estimated 44 percent year-over-year increase in tax refunds: a potent stimulative expected during the first half of the year.[5]

The bill also includes provisions for continued business investment and hiring, including extended 100 percent expensing for equipment and factories. These incentives align with the recent rotation we’ve seen into the industrials and materials sectors, as companies move to upgrade their physical and digital infrastructures.

Federal Reserve: Rate Relief or Regret?

The Federal Reserve is walking a high-stakes tightrope strung between two competing risks. On one side is the risk of a hiring slowdown and weakening consumers. On the other is the risk of still-elevated inflation with potentially significant government stimulus in the months ahead.

In 2025, investors and economists scrutinized labor market data for signs of weakness. And as usual, people found what they sought. Monetary doves advocating for faster and larger rate cuts bemoaned monthly payroll gains that slowed significantly throughout the year.

But those advocating for rate-cut patience view this data differently, pointing to the structural shift that occurred within the labor market this year: a sharp decline in net immigration. In a low-immigration economy with a low and falling birth rate, the break-even number of jobs required to keep unemployment stable is no longer as high as what we’ve become accustomed to. [6]

With strong economic growth, a stable labor market, low unemployment, and inflation that remains well-above-trend, Fed hawks and those advocating for patience have reasons for pause.

This tension is set to escalate in 2026 as political pressures reach a boiling point. Recent DOJ subpoenas served to Fed Chair Jerome Powell—just months before his term expires on May 15—have injected additional uncertainty. The President is expected to announce a successor in the next few months, and that person’s Senate confirmation process could be a contentious referendum on the Fed’s independence.[7]

Nonetheless, market expectations for rate cuts continue to show gradual easing throughout this year, with futures markets pricing in a gentle glide toward 3 percent by early 2027.

Consumer strength will likely play a role. The stark difference in spending behavior between wealthier households and those owning assets (such as homes and investment portfolios) compared to those with lower incomes and few assets continues to widen. The gap could create a potent political dynamic as we head toward midterm elections.

Midterm Uncertainty

No 2026 outlook would be complete without mentioning the midterm elections. Historically, midterm years exhibit higher volatility and lower returns than the other years of the political cycle, with an average intra-year S&P 500 drawdown of 19 percent. However, this volatility is often followed by recovery once election uncertainty resolves—regardless of the winning party. In fact, since 1950, the S&P 500 has shown a consistent track record of positive returns in the 12 months following a midterm election.[8]

A split-congress result could increase legislative gridlock and slow the pace of policy shifts, creating a more stable environment, which corporate decision-makers and markets often favor.

From Promise to Proof

The global economy has proved remarkably resilient to policy volatility that may have ordinarily derailed financial markets, including the radical reset of global trade, a structural shock to the labor market, escalating threats to Federal Reserve independence, and a continued fracturing of global relationships.

Yet one powerful force propelled markets through this noise to deliver a third consecutive year of exceptional gains: the unprecedented AI infrastructure investment cycle.

The size of the actors involved—and the sheer dollar magnitude of spending—transformed the AI theme into a form of direct, private-sector economic stimulus. But as we enter the show-me phase of the AI revolution, the staying power of this tailwind is in question.

Taken together, these factors suggest the year ahead could be noisy. But for long-term investors, what matters most is the strength of the underlying economy.

Corporate earnings growth expectations are healthy and broadening, and consumers continue spending. The broadening of market strength is a step in the right direction toward a less fragile market. And if AI can deliver on its promise of disinflationary growth, rising productivity has shown to be a force that can grow economies past a wide range of challenges and noise.

[1] “About 1 in 5 U.S. Workers Now Use AI in Their Job, Up Since Last Year,” Pew Research Center, October 6, 2025.

[2] J.P. Morgan, data as of 12/31/2025

[3] The Machine that Changed the World, Womack, James P., Daniel T. Jones, and Daniel Roos

[4] “Nestlé’s Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) Odyssey,” Worthen, Ben, CIO Magazine, May 15, 2002

[5] Strategas

[6] “Economic Issues to Watch in 2026,” Brookings Institution, Jan. 13, 2026

[7] “Statement from Federal Reserve Chair Jerome H. Powell,” Federal Reserve Board, Jan. 11, 2026

[8] Strategas

Investment advisory services offered by CapFinancial Partners, LLC (“CAPTRUST” or “CAPTRUST Financial Advisors”), an investment advisor registered under The Investment Advisers Act of 1940. This material is intended to be informational only and does not constitute legal, accounting, or tax advice. Please consult the appropriate legal, accounting, or tax advisor if you require such advice. The opinions expressed in this report are subject to change without notice. This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes. It may not apply to all investors or all situations and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. The information and statistics in this report are from sources believed to be reliable but are not guaranteed by CAPTRUST Financial Advisors to be accurate or complete. All publication rights reserved. None of the material in this publication may be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of CAPTRUST: 919.870.6822. © 2026 CAPTRUST Financial Advisors.

Index Definitions

Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur management fees, costs, and expenses, and cannot be invested in directly.

S&P 500® Index: Measures the performance of 500 leading publicly traded U.S. companies from a broad range of industries. It is a float-adjusted market-capitalization weighted index. Russell 2000® Index: Measures the performance of the 2,000 smallest companies in the Russell 3000® Index. It is a market-capitalization weighted index.

MSCI EAFE Index: Measures the performance of the large- and mid-cap equity market across 21 developed markets around the world, excluding the U.S. and Canada. It is a free float-adjusted market-capitalization weighted index.

Bloomberg U.S. Intermediate Govt/Credit Bond Index: Measures the performance of the non-securitized component of the U.S. Aggregate Index. It includes investment-grade, US Dollar-Denominated, fixed-rate Treasuries, government-related corporate securities. It is a market-value weighted index.

Bloomberg Commodity Index (BCOM): Measures the performance of 24 exchange-traded futures on physical commodities which are weighted to account for economic significance and market liquidity. BCOM provides broad-based exposure to commodities without a single commodity or commodity sector dominating the index.

MSCI Emerging Markets Index: Measures the performance of large and mid-cap stocks across 24 Emerging Markets countries. It aims to capture the performance of equity markets in emerging economies worldwide and covers approximately 85 percent of the free float-adjusted market capitalization in each country.

Silent Financial Stress in the Workplace: Data-Driven Insights for Decision-Makers

Financial stress is a growing challenge that impacts employee well-being and organizational performance. CAPTRUST’s Financial Wellness Survey Report explores this issue in depth, offering actionable strategies for employers and plan sponsors to strengthen financial wellness programs and support their workforce.

This comprehensive report includes:

- Key trends shaping employee financial wellness

- How financial stress influences workplace productivity and morale

- Practical steps employers can take to make a measurable impact

Gain data-driven insights and recommendations to help you:

- Improve employee engagement and retention

- Build more personalized financial wellness programs

- Close the gap between resource availability and utilization

Get the Full Report Here

Unlock the complete findings and strategies to empower your workforce.

Staying ahead of fiduciary deadlines is a big part of effective retirement plan governance. A proactive approach helps avoid penalties while reinforcing strong oversight, timely participant communication, and regulatory compliance.

Why Fiduciary Training and Timely Compliance Matter

Fiduciary training is a cornerstone of sound governance. A solid educational foundation—covering ERISA basics, investment‑monitoring best practices, and administrative responsibilities—enables plan fiduciaries to reduce risk and ensure their decisions are well‑documented and defensible.

Regulators, including the Department of Labor (DOL), closely evaluate prudence and process during audits. Meeting annual deadlines and staying current with plan requirements are therefore essential to protecting both the plan and its participants.

Q1 2026: Building the Foundation

- January: Gather and forward census data for the 2025 plan year to your recordkeeper or third-party administrator

- February 18: CAPTRUST Fiduciary Training Webinar Part 1

- March 15: Deadline for processing corrective distributions for any failed average deferral (ADP) or actual contribution percentage (ACP) test

Q2 2026: Testing, Audits, and Corrective Actions

- April 15: Deadline for returning excess deferrals for 402(g) violations

- April–June: Initiate independent plan audit

Q3 2026: Heavy Compliance Season

- July: Complete independent plan audit, if applicable

- July 31:

- Deadline for sending Summary of Material Modifications (SMM) for any prior-year plan amendments

- Deadline for filing Form 5558 to extend the Form 5500 filing date

- Deadline for filing Form 5500 without filing an extension

- September 30: Distribute the Summary Annual Report (SAR) if Form 5500 is filed by July 31

Q4 2026: Final Requirements and Participant Notices

- October 15: Deadline for filing extended 2024 Form 5500

- October 1–December 1: Distribute annual participant notices (safe harbor, ACA, QDIA, etc.)

- December 31: Deadline for required minimum distributions

A downloadable PDF version of this calendar is available below. Your CAPTRUST financial advisor can help guide you through the year.

Sources: CAPTRUST research, DOL, IRS

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and does not constitute an offer, solicitation, or recommendation to sell or an offer to buy securities, investment products, or investment advisory services. Data contained herein from third-party providers is obtained from what are considered reliable sources. However, its accuracy, completeness, or reliability cannot be guaranteed. Nothing contained herein constitutes financial, legal, tax, or other advice. Consult your tax and legal professional for details on your situation. Investment advisory services offered by CapFinancial Partners, LLC (“CAPTRUST” or “CAPTRUST Financial Advisors”), an investment advisor registered under The Investment Advisers Act of 1940.

Existing Deductions and Credits

As you prepare to file your 2025 federal income tax return, some items will look familiar but with small changes.

Standard Deductions: According to the IRS, more than 87 percent of filers take the standard deduction instead of itemizing. If you fall into this category, you will see a slight increase in the standard deduction. The new standard deduction amount is $15,750 for single filers and $31,500 for those who are married filing jointly.

However, if you itemize your deductions, you have a larger hurdle to clear for 2025. Once OBBBA became law, the higher standard deduction was made permanent and will be indexed to inflation. This means the majority of taxpayers will continue to enjoy a larger decrease to their overall taxable income.

SALT: One frequently discussed and sometimes hotly debated topic is the state and local tax (SALT) deduction, which increased from $10,000 to $40,000 for most filers in 2025. An increase in the SALT limit benefits people who live in states with higher state income and property taxes, and those who own high-priced real estate.

There’s a catch though. If you have an adjusted gross income (AGI) between $500,000 and $600,000, your ability to deduct SALT begins to phase out. Once your AGI reaches $600,000, the opportunity to deduct up to $40,000 in SALT is completely diminished to the original $10,000. For those filers who are married filing separately, the SALT deduction is limited to $20,000 but begins to phase down at $250,000 AGI.

Tax planning strategies to decrease AGI below these limits will allow those with large property taxes or state income taxes to deduct more than they’ve been able to in the recent past. The SALT deduction was one part of OBBBA that wasn’t made permanent. After adjusting 1 percent each year for inflation, it will return to a $10,000 deduction on January 1, 2030, and will likely remain a hot topic until a more permanent solution is found.

Additional Child Tax Credit: If you were eligible for the Child Tax Credit in previous tax years, you will notice an increase from $2,000 to $2,200 per qualifying child on your 2025 tax return. The extra $200 per qualifying child directly reduces your tax liability dollar for dollar. This higher amount was made permanent by OBBBA and will be indexed for inflation going forward, but the phaseout rules remain unchanged and are not indexed to inflation.

Households with an AGI over $200,000 (single) and $400,000 (joint) will continue to see a reduction in the child tax credit of $50 for every $1,000 of AGI above the limits.

New Deductions

The OBBBA not only made permanent some provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), it also added some new deductions that went into effect for the 2025 tax year. If you are eligible for any or all these new below-the-line deductions, they are available to you even if you don’t itemize.

65 and Older: If you’re age 65 or older, you may notice an additional deduction of up to $6,000 per person that will reduce your taxable income when you file your 2025 taxes. Often touted as “no tax on Social Security,” this new deduction is available only from 2025 through 2028 and does not reduce your AGI to determine how much of your Social Security income is taxed or how much you pay for Medicare premiums.

Furthermore, if you have an AGI of $75,000-$175,000 (single) or $150,000-$250,000 (joint), your 65+ deduction will begin to decrease and will be $0 once you reach the upper limit. Managing your AGI will be important as you weigh the benefits of this deduction.

Tips and Overtime: If you receive overtime or tips as part of your compensation, you may also notice a new deduction from 2025 through 2028. For overtime, that deduction maxes out at $12,500 (single) or $25,000 (joint) and begins to phaseout by $100 per $1,000 of AGI above $150,000 (single) or $300,000 (joint).

Similarly, if you receive tips, the maximum deduction for all filers is $25,000 with the same phaseout limits that apply to overtime. It is important to note that this is not “no tax on overtime or tips” and that these earnings are still subject to payroll tax and state tax. They are also still included in your AGI.

Future Planning Opportunities

Paying close attention to AGI over the next several years will be imperative for tax planning. Each deduction or credit has its own set of phaseout rules that makes eligibility feel like a moving target.

Strategies to decrease AGI such as contributing more pre-tax dollars to your retirement account, health savings account (HSA), or deferred compensation plan may be appropriate to ensure you maintain an AGI that leaves your eligibility intact. If you don’t have earned income and are already taking required minimum distributions (RMDs), you may consider qualified charitable distributions (QCDs) to reduce your AGI.

If you’re on the edge of eligibility for these deductions, do your due diligence to remain aware of strategies that can increase your AGI. Tax strategies such as taking Social Security before age 70, Roth conversions, contributing less to deferred compensation plans, or changing the split of pre-tax vs. Roth contributions to retirement accounts will increase your AGI. A cost-benefit analysis can help you determine if a strategy that increases AGI is appropriate. Consult with your financial advisor and tax professional for guidance.

Sources: “SOI Tax Stats,” IRS; CAPTRUST research

Disclosures: This content is provided for informational purposes only, and does not constitute an offer, solicitation, or recommendation to sell or an offer to buy securities, investment products, or investment advisory services. Data contained herein from third-party providers is obtained from what are considered reliable sources. However, its accuracy, completeness, or reliability cannot be guaranteed. Nothing contained herein constitutes financial, legal, tax, or other advice. Consult your tax and legal professional for details on your situation. Investment advisory services offered by CapFinancial Partners, LLC (“CAPTRUST” or “CAPTRUST Financial Advisors”), an investment advisor registered under The Investment Advisers Act of 1940.

Retirement plans hold trillions of dollars in assets, making them a potentially attractive target for cybercriminals. In this CE-accredited webinar, we’ll explore the growing cybersecurity risks facing qualified retirement plans and the steps fiduciaries, service providers, and advisors can take to protect sensitive participant data and plan assets.

Join us on February 18, 2026, at 4 p.m. Eastern Standard Time as we cover:

- The latest Department of Labor (DOL) guidance on cybersecurity for retirement plans

- Practical tips for hiring service providers with strong cybersecurity practices

- Cybersecurity program best practices for plan sponsors and recordkeepers

- The critical role financial advisors play in mitigating cyber risks

Through real-world examples, including recent litigation and regulatory developments, you’ll gain actionable insights to strengthen your plan’s defenses and fulfill your fiduciary responsibilities.

2026 Fiduciary Training Series, Part 1: Cybersecurity Risks in Retirement Plans Registration Link

CE offered:

- This program is valid for 1 PDCs toward SHRM-CP® and SHRM-SCP® recertification.

- Participants will earn 1.0 CPE credit. Program is free.

- To receive CE credit, you must remain logged into the video portion of the webinar for the entire program. Logging into the audio portion only is not sufficient for CE credit. In order to be awarded the full credit hours, you must be present for the entire session, registering your attendance and departure in the webinar and answering all polling questions.

Field of Study: Specialized Knowledge

Additional Information:

Date and Time: February 18, 2026, 4 p.m. Eastern Standard Time

Prerequisites: 3-5 years experience in the industry

Who should attend: Plan sponsors, financial professionals, and accountants; others are welcome

Advanced Preparations: None

Program Level: Intermediate

Delivery Method: Group Internet Based

Refunds and Cancellations: For more information regarding refund, complaint and program cancellation policies, please contact our offices at 218-828-4872 or email info@cecenterinc.com.

Continuing Education Center, Inc. is registered with the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) as a sponsor of continuing professional education on the National Registry of CPE Sponsors. State boards of accountancy have the final authority on the acceptance of individual courses for CPE credit. Complaints regarding registered sponsors may be submitted to the National Registry of CPE Sponsors through its website: www.NASBARegistry.org.

Additional CAPTRUST Resources

Our 2025 Series:

- 2025 Fiduciary Training, Part 1: Best Practices for Plan Sponsors

- 2025 Fiduciary Training, Part 2: Effective Plan Governance

- 2025 Fiduciary Training, Part 3: Elevating Plan Design

- 2025 Fiduciary Training, Part 4: Fiduciary Risk Litigation

- The Importance of Fiduciary Training

Our 2024 Series:

- 2024 Fiduciary Training Series, Part 1: Roles and Responsibilities

- 2024 Fiduciary Training Series, Part 2: Plan Governance

- 2024 Fiduciary Training Series, Part 3: Fiduciary Risk Management

- 2024 Fiduciary Training, Part 4: Avoiding Scams&title=2025%20Fiduciary%20Training%20Series,%20Part%202:%20Effective%20Plan%20Governance%20(Webinar%20Recording)?action=genpdf&id=45803Feed

1. Legislation: Rulemaking, Preparation, and Signaling

New Guidance on Alternative Assets: The Department of Labor (DOL) is expected to release new guidance addressing alternative assets in defined contribution (DC) plan menus. This would be a significant development for sponsors exploring private market allocations. “Without guidance, many sponsors have hesitated to offer alternatives because of liability concerns,” says Charlie MacBain, CAPTRUST manager of DC allocation solutions. “Once the lines are drawn, we could see an uptick in interest, especially among larger plans.”

Target-Date Funds Evolve Toward Retirement Income and Alternatives: 2026 could mark a shift in how major target-date fund providers position their products. MacBain anticipates leading firms will begin to offer target-date funds that embed allocations designed for retirement income and private-market or other alternative strategies in their glidepaths. “The industry has moved beyond just accumulation,” he says. “As participants approach retirement, sponsors and providers will increasingly look to built-in income solutions to assist with decumulation.”

“There is also a desire for increased portfolio diversification in a world in which the public opportunity set is shrinking,” says Jennifer Doss, CAPTRUST defined contribution practice leader. “In the U.S., 87 percent of companies with revenue greater than $100 million are private, according to Apollo Global Management.”1

Policy Signaling and Prepping for SECURE 3.0 Act and Beyond: 2026 is also likely to bring an increase in retirement-related legislative activity. “We anticipate new bills in both congressional chambers,” says Doss. “These won’t necessarily be focused on final passage but, rather, intended to send signals to stakeholders about support or opposition to retirement policy proposals.” These bills could also become building blocks to an eventual SECURE 3.0 Act package, potentially in 2027.

“This signaling matters because it helps shape business planning cycles, influences vendor roadmaps, and sets expectations for what retirement plan sponsors should budget and prepare for,” says Doss.

Attention Turns to the Saver’s Match: As implementation of the Saver’s Match provision draws near, 2026 should see greater focus—from regulators, plan sponsors, and recordkeepers—on how to operationalize and communicate the benefit. The Saver’s Match is a new federal incentive created by the SECURE 2.0 Act to replace the existing IRS Saver’s Credit starting in 2027. Instead of a nonrefundable tax credit, the government will directly deposit matching contributions into eligible retirement accounts for those who qualify.

“This provision is a major step toward improving retirement security for lower-income earners,” says Lori Dillingham, CAPTRUST senior director of vendor analysis and plan consulting. “Plan sponsors should start planning for participation, administrative processes, and communication strategies in 2026.”

ESG and Proxy Voting: A Return to 2020-Era Standards: We also expect the DOL to revisit its guidance on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factor considerations and proxy-voting responsibilities for retirement plan fiduciaries. Most likely, it will roll back the less restrictive interpretation that emerged in recent years and restore a framework like what applied in 2020. This recalibration should sharpen the focus for plan sponsors that are evaluating whether and how to include ESG options in their plan menus. “As sponsors assess their fund lineups, decisions around ESG funds are going to come under renewed scrutiny, both from a compliance standpoint and from a cost-benefit lens,” says Dillingham.

2. Litigation: Heightened Scrutiny and Broader Claims

Ripple Effects from the Cornell ERISA Case: The recent ruling in the Cunningham v. Cornell University case has the potential to reshape retirement litigation. We expect its ripple effects to continue into 2026 and beyond. “We could see a wave of new prohibited-transaction claims layered onto traditional fiduciary-breach allegations, especially in cases where recordkeeping fees are involved,” says Doss. Where prior claims might have been dismissed early on procedural grounds or narrow fiduciary-prudence arguments, this broader approach could survive early-stage motions to dismiss, raising the stakes for plan sponsors.

“On the bright side, we do expect the Department of Labor under this administration to provide more visible support for plan sponsors, most likely through amicus briefs and additional guidance on key topics,” says Doss.

For a more in-depth discussion of the Cornell decision and its potential impacts, listen to episode 77 of Revamping Retirement.

Scrutiny on Capital Preservation: With interest rates having risen substantially from 2022 through 2025, we expect increased scrutiny around capital preservation vehicles, comparing different types of stable-value offerings to each other and to money market funds. “Most of the cases we’re seeing thus far are around the concept of imprudent retention of an underperforming stable-value fund, either versus alternative stable-value options or against higher-yielding money market options,” says Dillingham. “Any time we see a dispersion of returns like we have seen in the capital-preservation space over the last few years, it’s bound to catch the eye of the law firms looking for new cases to bring.”

3. Fiduciary Solutions: Evolution of Plan Design and Outsourcing

Continued Growth in Discretionary Outsourcing: As has been true for the past few years, we continue to expect further adoption of discretionary relationships: both investment outsourcing under a 3(38) fiduciary and administrative outsourcing via 3(16) plan administrator relationships. “Sponsors are looking for ways to manage increased complexity,” says Doss. “The value of outsourcing has become clear and commonplace. As litigation risk and regulatory requirements rise, discretionary outsourcing is growing from a simple convenience to a strategic necessity for many organizations. In some cases, it’s also a way to reduce plan costs.

4. Participant Outcomes: Personalization, Innovation, and Accessibility

AI-Powered Communications and Education Go Mainstream: One of the biggest changes we expect in 2026 is an increase in artificial intelligence (AI) used for participant communications content and education. From personalized retirement readiness emails to chatbot-based financial-wellness support, AI-driven tools are already allowing sponsors to deliver timely, tailored, and cost-effective retirement guidance at scale.

“Further AI adoption will improve efficiency, and it will enable more responsive, nuanced communication strategies,” says Chris Whitlow, head of CAPTRUST at Work, the firm’s financial wellness solution for employers. For example, AI can help nudge participants when their match eligibility changes, flagging auto-escalation opportunities or simplifying complex design features like student loan matching.

However, “to access AI’s potential for personalization, plan sponsors will need to become more comfortable with how employee data is being stored and accessed,” says Whitlow. “This could be a hot topic in 2026.”

The average consumer has come to want, and sometimes expect, a personalized experience. For employers, the cost of offering personalization is deeper and more detailed data sharing. “Giving this level of access to a vendor-partner can feel uncomfortable,” says Whitlow. “But with recent advancements in data security, policies, processes, and care, sponsors can provide personalized experiences while also keeping employee information safe and private.”

More Personalized Investment Solutions: 2026 is also likely to see a rise in personalized investment management programs. Managed accounts and custom target-date offerings will become more accessible and cost-effective, even for smaller plans. “These options are no longer just for large employers,” says Doss. The democritization of personalization could help reduce disparities in retirement readiness across employee populations.

What This Means for Plan Sponsors

If 2026 unfolds as we expect, plan sponsors will need to be proactive. The combination of evolving regulation, heightened litigation risk, and changing participant expectations means that plan design and oversight will be more complex than ever but also more opportunity rich.

- Now is a good time to review your investment menu strategy. With changing ESG and alternative-asset rules and evolving target-date and managed account offerings, sponsors should assess whether their existing lineup aligns with long-term goals, fiduciary objectives, and participant demographics.

- Consider outsourcing fiduciary and administrative responsibilities, especially if your plan is growing or if you face increased complexity. A thoughtful 3(38) or 3(16) fiduciary arrangement can help reduce risk and increase bandwidth.

- Begin planning now for new benefits and design changes, such as the Saver’s Match or new income-oriented fund options, before vendors and recordkeepers begin rolling them out.

- Be prepared to leverage technology. Those who want to offer personalization should learn more about data-sharing practices and processes.

- Finally, document well. As litigation risk increases, a clear fiduciary process, well-documented decision-making for menus, and consistent communication will become increasingly important.

1 “Many More Private Firms in the U.S.,” Apollo Global Management

Additional Sources: SECURE 2.0 Act, irs.gov, dol.gov, CAPTRUST research

DISCLOSURE: This content is provided for informational purposes only, and does not constitute an offer solicitation, or recommendation to sell or an offer to buy securities, investment products, or investment advisory services. Data contained herein from third-party providers is obtained from what are considered reliable sources. However, its accuracy, completeness, or reliability cannot be guaranteed. Nothing contained herein constitutes financial, legal, tax, or other advice. Consult your tax and legal professional for details on your situation. Investment advisory services offered by CapFinancial Partners, LLC (“CAPTRUST” or “CAPTRUST Financial Advisors”), an investment advisor registered under The Investment Advisers Act of 1940.

A SLAT allows one spouse to gift assets to a trust for the benefit of the other spouse or their dependents. This transfer removes the gifted assets from the estates of both spouses and, depending on how the trust is structured, from the estates of the dependents as well.

How It Works

Assets transferred to a SLAT are removed from the transferring spouse’s estate, the receiving spouse’s estate, and potentially the estates of their children. As a result, these assets are not subject to probate and will not trigger estate taxes upon the death of either spouse or their children—even if the assets have appreciated in value.

Key Benefits of a SLAT

A SLAT offers multiple advantages, including:

- avoidance of probate

- avoidance of estate taxes

- transfer of tax-free appreciation

- the ability to own life insurance policies and pay premiums

- asset protection

- some access to trust assets through the beneficiary spouse

Assets in a SLAT are well protected from claims by creditors of the spouses and other beneficiaries. Importantly, the transferring spouse does not lose all access to the assets; they can still indirectly benefit through the other spouse. A SLAT is also an excellent vehicle for owning life insurance, which can further leverage its benefits.

Why SLATs Stand Out Among Gifting Strategies

Most gifting strategies require the taxpayer to give assets away with no strings attached. For couples with assets ranging from $20 million to $75 million, this can feel risky, especially when considering gifts of $10 million or $20 million that might be needed later.

A SLAT, coupled with life insurance, can offer the best of both worlds, including:

- a completed gift

- removal of trust assets from a couple’s gross estate

- a tax-favored, leveraged death benefit

All of this comes with the added flexibility of allowing the beneficiary spouse access to trust investment values if needed in the future.

Leverage SLATs for tax Efficiency

By transferring assets into a SLAT, individuals can leverage current gift and estate tax exemptions while maintaining indirect access to trust assets through their spouse. This strategy can help preserve wealth for future generations and minimize federal tax liability.

Because tax laws and exemptions can change over time, it’s important for individuals and families to work closely with their advisors to evaluate whether a SLAT aligns with their long-term financial and estate planning goals.

SLATs are typically grantor trusts, meaning the transferring spouse is responsible for paying income taxes on the trust investments. This arrangement allows the transferor to pay those taxes without the government treating the payments as an additional gift. Generation-skipping transfer tax planning can also be included in SLATs.

Current Exemptions and Potential Changes

Estate and gift tax exemptions—and the rates applied to them—are often subject to legislative changes. Beginning January 1, 2026, the federal unified estate and gift tax exemption is $15 million per taxpayer, with annual inflation adjustments. This change was made permanent by the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), signed into law in 2025.

This means an individual can make lifetime gifts of property or cash valued at or up to $15 million without paying federal gift taxes. For federal estate taxes, an individual may leave an estate of up to $15 million without incurring federal estate tax at death.

It is important to note that gift and estate exemptions are unified. This means if the exemption amount is used for gifts during life, the estate tax exemption is reduced, dollar for dollar. Only the remaining balance, if any, is available to offset estate taxes. Amounts exceeding the exemption are taxed at a federal rate of 40 percent.

Is a SLAT Right for You?

If you think a SLAT may benefit you, start a conversation with your financial advisor. While SLATs offer many advantages, the best approach depends on your unique circumstances.

Although no one can predict the future of estate and gift tax exemptions, one thing is certain: uncertainty. Planning now with a SLAT can help you take advantage of current exemptions while hedging against potential reductions in the future.

Source:

Internal Revenue Service, n.d. “Internal Revenue Service | an Official Website of the United States Government.” Irs.gov. https://www.irs.gov/.

Important Disclosure

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and does not constitute an offer, solicitation, or recommendation to sell or an offer to buy securities, investment products, or investment advisory services. Data contained herein from third-party providers is obtained from what are considered reliable sources. However, its accuracy, completeness, or reliability cannot be guaranteed. Nothing contained herein constitutes financial, legal, tax, or other advice. Consult your tax and legal professional for details on your situation. Investment advisory services offered by CapFinancial Partners, LLC (“CAPTRUST” or “CAPTRUST Financial Advisors”), an investment advisor registered under The Investment Advisers Act of 1940.