Striking a Balance on Spending

Since then, they’ve taken a 7,000-mile train trip, toured the country in their RV, and purchased a second home near their daughter, son-in-law, and three-year-old granddaughter. Their primary home, a 2,000-square-foot cabin in Blue Ridge, Georgia, is a step up from the vacation cabin they first moved to after selling their big family home in Atlanta.

Recently, they added a woodworking shop that doubles as a writing studio for Gilbert, who is the author of a blog, The Retirement Manifesto, and a book, Keys to a Successful Retirement: Staying Happy, Active, and Productive in Your Retired Years.

“We’re in the go-go years,” says Gilbert, 58. “We’re young, we’re healthy, we’re traveling. We are not worried. We are enjoying ourselves.”

Are the Gilberts crazy not to worry? Or are they on to something?

They are definitely on to something.

While many American retirees do indeed need to scrimp in order to keep paying their bills, many others have a nicer problem, financial researchers say.

If these well-funded retirees don’t start spending more of what they have, they may die with their nest eggs largely intact or expanded—even if they never consciously decided to do so.

While surviving family members, charities, or other beneficiaries may appreciate such sacrifices, there’s a price, says Sarah Asebedo, an assistant professor in the school of financial planning at Texas Tech University. “The downside is life not lived,” she says. “If you don’t pull the money out, if you don’t spend it, what are you missing out on? What are you holding back on? What are you giving up?”

The things you could miss out on—from travel to family time to doing good works—are exactly the things you probably saved for in the first place, she and other experts say.

The Retirement Consumption Gap

In the dry lingo of academia, this underspending problem is called the retirement consumption gap. It’s unclear how common this somewhat enviable affliction is. But recent research provides some clues.

One study published in 2021 in the Journal of Financial Planning found that just 18 percent of newly retired Americans had enough wealth to keep spending at preretirement levels. But a funny thing happened as people settled into retirement.

Almost everyone, at every wealth level, spent less. In most cases, this was a good move, a matter of right-sizing spending to fit available resources, co-authors David Blanchett and Warren Cormier reported. They found that 10 years into retirement, 48 percent of households had the resources to support their spending.

But because well-funded households typically cut back on spending, as well, many actually spend much less than they could afford.

“We see too many households err on the side of not spending when they’re younger in retirement” for fear of running out of money when they are older, says Blanchett, who is managing director and head of retirement research for PGIM DC Solutions, the global investment management business of Prudential Financial.

Another study, also published in the Journal of Financial Planning in 2021, found that average retirees in the top three-fifths of income spent less than they took in from Social Security, pensions, investment earnings, and other income sources. The researchers, led by Asebedo’s Texas Tech colleague Christopher Browning, then looked at how that consumption gap might affect overall assets over a 30-year retirement under various investment scenarios.

Their conclusion? Even if a generous 40 percent of the portfolio was set aside for late-in-life medical expenses and bequests, a retiree with a mid-level income might underspend by as much as 8 percent. The wealthiest retirees might use 47 percent less than they could safely spend.

“Retirees in the top quintile of financial wealth were spending nowhere near an amount that would place them in danger of running out of money,” the researchers concluded.

Understanding the Underspending Mindset

Mike Gray, a CAPTRUST financial advisor based in Raleigh, North Carolina, says he sees plenty of people who haven’t saved and invested nearly enough to keep up their spending in retirement. These folks may have enjoyed six-figure incomes, nice homes, pricey vacations, and other trappings of a comfortable lifestyle, but they never saved more than the bare minimum in a 401(k) plan. Many are unpleasantly surprised to learn that they must live more modestly in retirement, he says.

But Gray also sees plenty of potential under-spenders among diligent lifelong savers. For example, take a couple who have $3 million in retirement accounts and are used to living well within their means, Gray says. “If spending doesn’t change during retirement at all, and they don’t do any travel or anything outside the realm of their normal budget, what ends up happening is that their asset base grows year after year after year until they pass away.”

All of a sudden $3 million is $12 million, Gray says. “You show them that and say, ‘OK, what do you want to have happen with this?’ And their eyes kind of go wide and they say, ‘Oh, wow, I never thought about that.’”

But nudging people to spend more isn’t a simple matter of showing them an eye-popping projection. That’s because good savers often have personality traits that make them uneasy spenders, Asebedo says. In one study, she and Browning found some of the lowest portfolio withdrawal rates among people who showed the highest levels of conscientiousness.

“These are the quintessential savers, the budgeters, the ones who have all the checklists,” she says.

Spending more may literally make such people queasy, Asebedo says.

“We expect people to just flip a switch once they get to retirement. We say, ‘OK, it’s time to take money out, it’s time to spend.’ And I think we underestimate what kind of a psychological leap that can be for a lot of people because of the years and years of blood, sweat, and tears and self-control it took to put that money in. It actually can feel painful and nauseating for some people to pull money out.”

Blanchett agrees. “People spend all these years socking away money … then all of the sudden to change that mindset from ‘save, save, save’ to ‘spend, spend, spend,’ that’s just not easy.” He says many people envision their portfolios as “this gigantic pot of money” that must be protected because it can never be replaced.

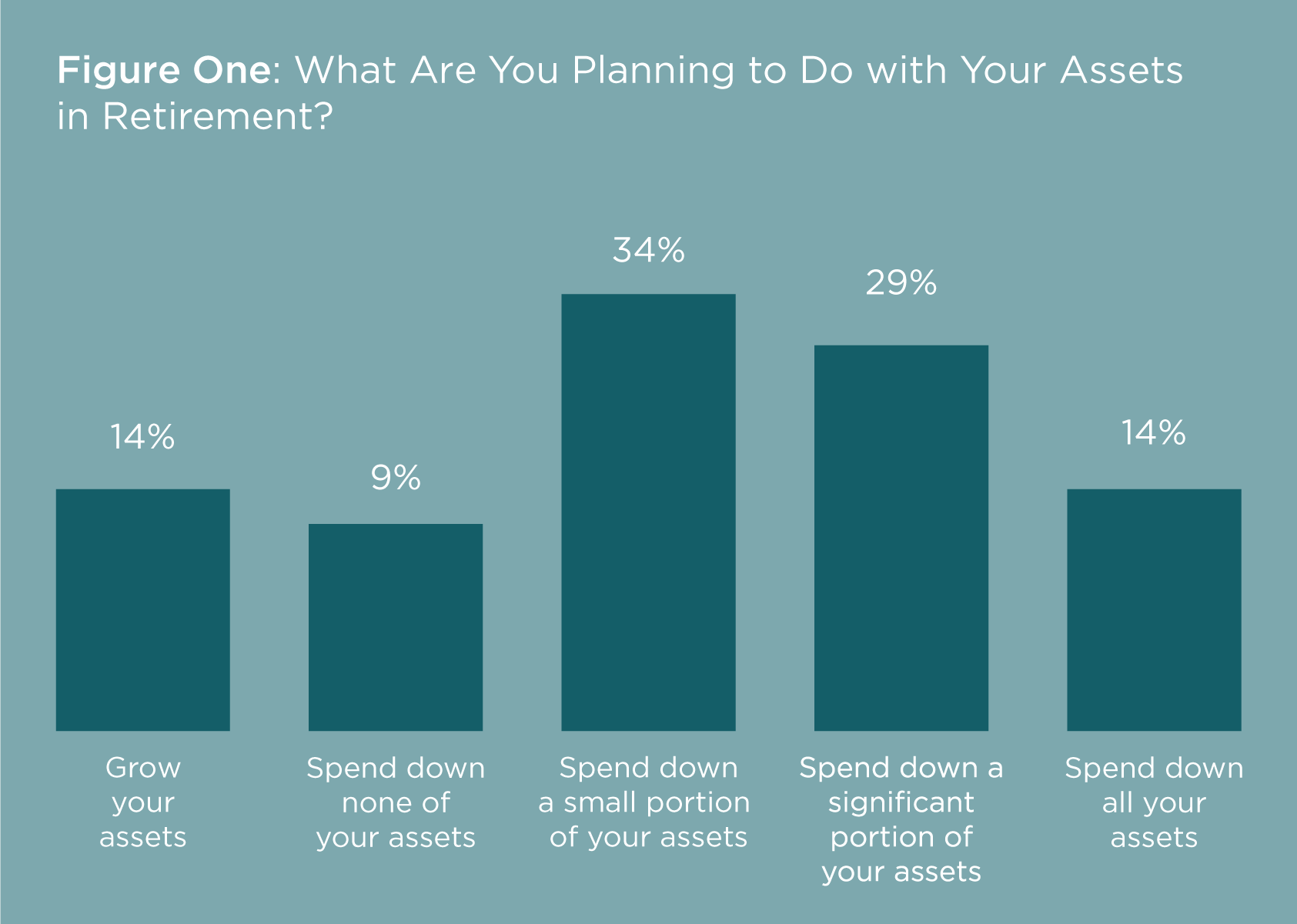

In fact, according to a September 2020 Employee Benefit Research Institute survey of 2,000 Americans ages 62 to 75, only 14.1 percent think they’ll spend down all their assets. Moreover, as shown in Figure One, nearly 60 percent plan to grow their assets in retirement, leave them untouched, or spend them down only a little.

Source: Employee Benefit Research Institute

The objections to spending go beyond gut feelings, of course. People who retire at 60 or 65 are worried about their healthcare needs if they live to be 90 or 95. Or they are worried they may need to financially support an aging parent or a struggling adult child. Some are highly motivated to leave large sums to their children, though Gray says such folks are in a distinct minority. Some have other bequests in mind. Many are worried about maintaining their lifestyles if markets tank in the future.

The secret to loosening the purse strings without losing peace of mind? It’s all about planning.

Enjoying the Well-Planned Retirement

Allen Chamberlain, a retired schoolteacher and librarian from Richmond, Virginia, might seem like the sort of person who would have trouble spending her retirement savings.

Chamberlain, 68, says she grew up with parents who “were pretty remarkable savers, even though they were not high income.” She tried to follow in their footsteps during her working years, contributing as much as she could to her retirement plan and sticking to a conservative but effective investment strategy. She also received an inheritance from her thrifty parents.

Before she retired at age 65, she worked with her financial advisors, including Gray, to come up with a plan for making her money last. “I came up with a budget of what was really necessary and what was important to me, and that helped me see what was possible,” she says.

Under her plan, she gets a monthly income from her portfolio that goes straight into her checking account. With that income, along with Social Security, she says she lives a comfortable but not extravagant life.

One luxury she allows herself and has budgeted for is regular extended trips overseas to visit her grown daughter, Evie, who lived for several years in Edinburgh, Scotland, and now lives in Zurich, Switzerland.

Chamberlain says her planning also allows for flexibility. She says that when she wanted to withdraw $30,000 to renovate two bathrooms in the home she shares with her partner of 31 years, she checked with her CAPTRUST advisors.

They reassured her that the expense would not throw her long-term plans off track or force her to cut corners. “They were able to assure me that ‘you’ve got this,’ because of the careful planning in place.”

Planning is also the secret to the Gilberts’ active lifestyle. Before he retired, Fritz Gilbert says he and his wife decided they could safely withdraw 3.3 percent each year from their portfolio. That’s in the conservative range recently endorsed by some financial forecasters worried about future market downturns, Gilbert notes.

His plan also includes spending less in later years when healthcare costs typically rise but other wants and needs tend to decline. The Gilberts also plan to leave a pool of money available in case either of them needs costly long-term care.

“You’ll never alleviate all the risks, but you do what you can to alleviate the most likely risks,” Gilbert says.

And then, he says, you live your life and, ideally, think very little about money. Like Chamberlain, Gilbert has a paycheck sent monthly to his checking account. And that money, he says, is money he feels very comfortable spending.

On a typical day at home, he is exercising, writing, or building something in his workshop. His wife is busy running a nonprofit called Freedom for Fido that provides doghouses and fences to families that would otherwise leave their dogs on chains.

One week a month, they load up their own four dogs and head to their condo in Alabama to spend time with their daughter and her family. When money builds up in their checking account, they spend and enjoy it—because, Gilbert says, that’s why they saved it in the first place.

“We are not recklessly optimistic,” he says. “But we live optimistically.”