Leading New Troops: From the Marine Corps to the Girl Scouts

She wasn’t at ease for long.

Salinas started receiving calls about careers with Fortune 500 companies, but nothing felt right. Then she heard from a headhunter about leading the Girl Scouts in her area.

“It was the first phone call I got excited about,” says Salinas, 68. “I realized this was a chance to impact the next generation of leaders.”

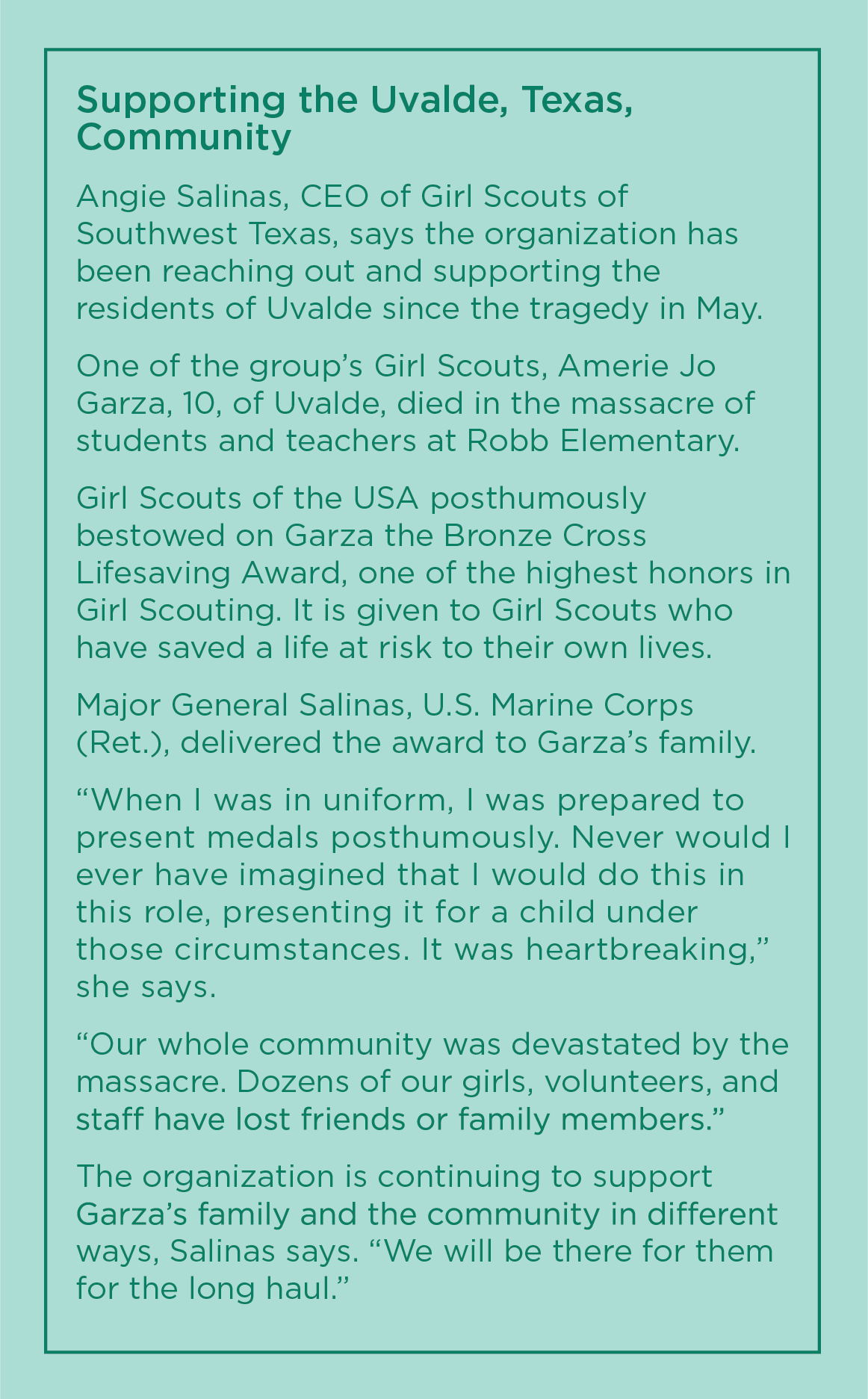

In 2015, she became chief executive officer of Girl Scouts of Southwest Texas, based in San Antonio, overseeing the nonprofit’s operation, which then included 21,000 Girl Scouts and adult volunteers in a 21-county area.

“The reason I took this job is every single Girl Scout wears the American flag on her sash and her vest,” Salinas says. “Every meeting starts with the Pledge of Allegiance and the Girl Scout Promise. I get to work with girls who, at the age of five, raise their hands and say the words, ‘On my honor, I will try to serve God and my country.’”

“There’s my link,” she says. “To me, it’s the patriotism, because being in the military, I am a patriot. This is one of the few organizations today that still teaches patriotism.”

Growing Up in Texas and California

Salinas’s life took several surprising turns before she landed where she is today. She was born in Alice, Texas, the youngest of five children. When she was in fourth grade, her family moved to Vallejo, California.

Both her father, a mechanic, and her mother, a housecleaner, were smart and hardworking but struggled financially. They tried to do everything they could to help her blend in, so they got her into Girl Scouts. “I didn’t quite feel welcome because I didn’t look like the other girls, but I was proud of the green uniform, yellow tie, and beret,” Salinas says.

Navigating New Territory

After high school, Salinas knew she needed an advanced education to chart a different course for herself, so she enrolled in Dominican College (now Dominican University) in San Rafael, California. “Nobody in my family had completed college when I went,” she says. “But we understood that if we wanted to get ahead, we had to go.”

There were only three Hispanic students in the school, she says. “Nobody looked like me. I had bad study habits. I had no support. I was good at one thing—I partied. My grades showed it. I was at the bottom of my class.”

She considered dropping out. “I had convinced myself that people like me don’t go to college,” Salinas says. “We are domestics. We clean houses. We work at McDonald’s. We are not the people who rise in the world.”

That was 1974, and the Vietnam War was winding down. “Americans were burning the flag. Military service members were afraid to wear their uniforms.”

In the spring, Salinas, 19, was walking to mail a letter when a chance meeting with a Marine recruiter changed her life. He said to her, “Why aren’t you a Marine?”

“I said, ‘Look buddy, I’m just trying to mail a letter.’”

Looking back, she says, “I believe it was truly fate. That was April 30. On May 4, I was taking the oath: ‘I do solemnly swear that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic.’”

On May 7, she reported to boot camp in Parris Island, South Carolina.

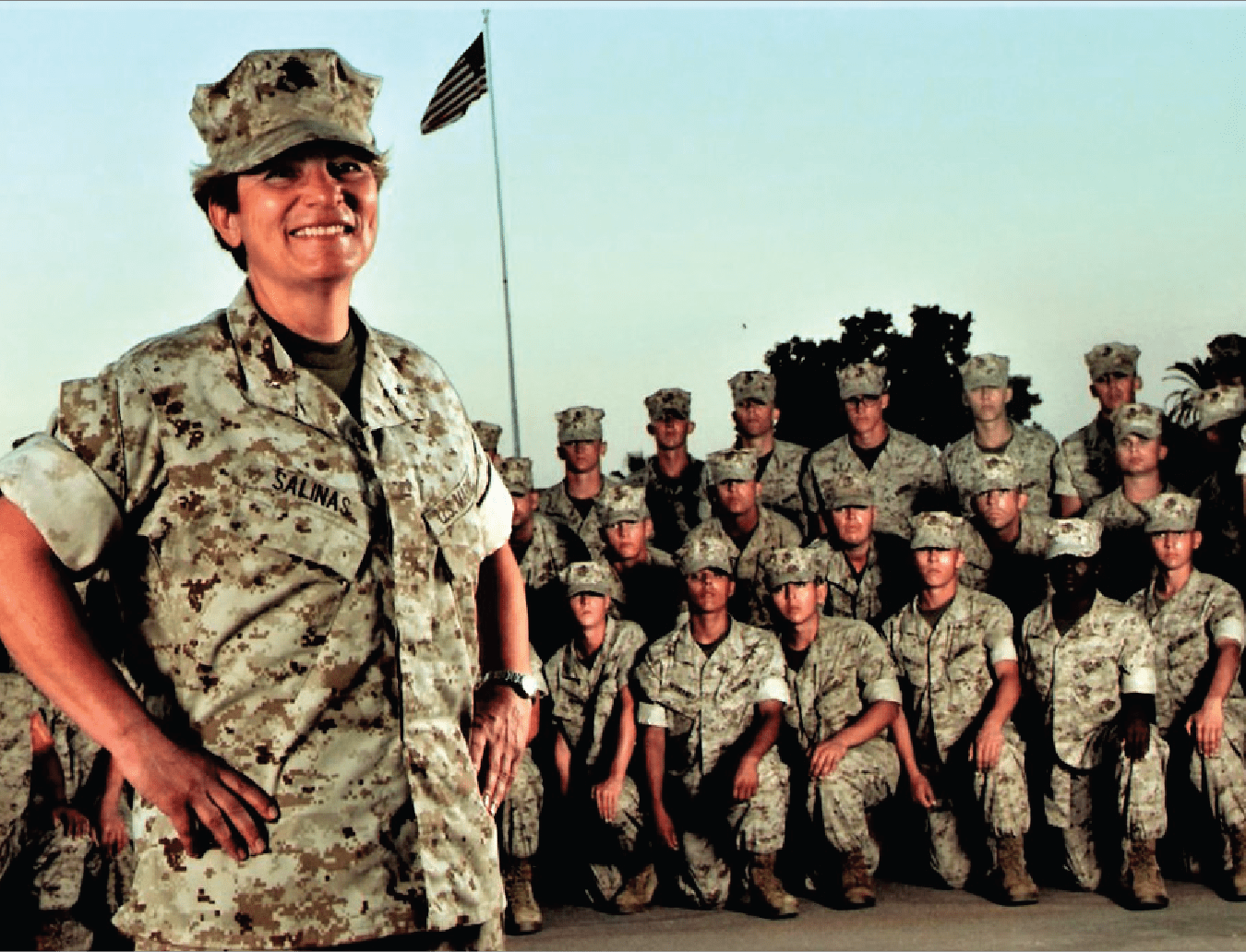

“I was being dressed down,” Salinas says. “I had abandoned my civilian identity. I was now recruit Salinas. I was standing there wondering what I’d done. The transformation had begun. My entire life changed from almost being a college dropout to where I sit today. It was a blessing.”

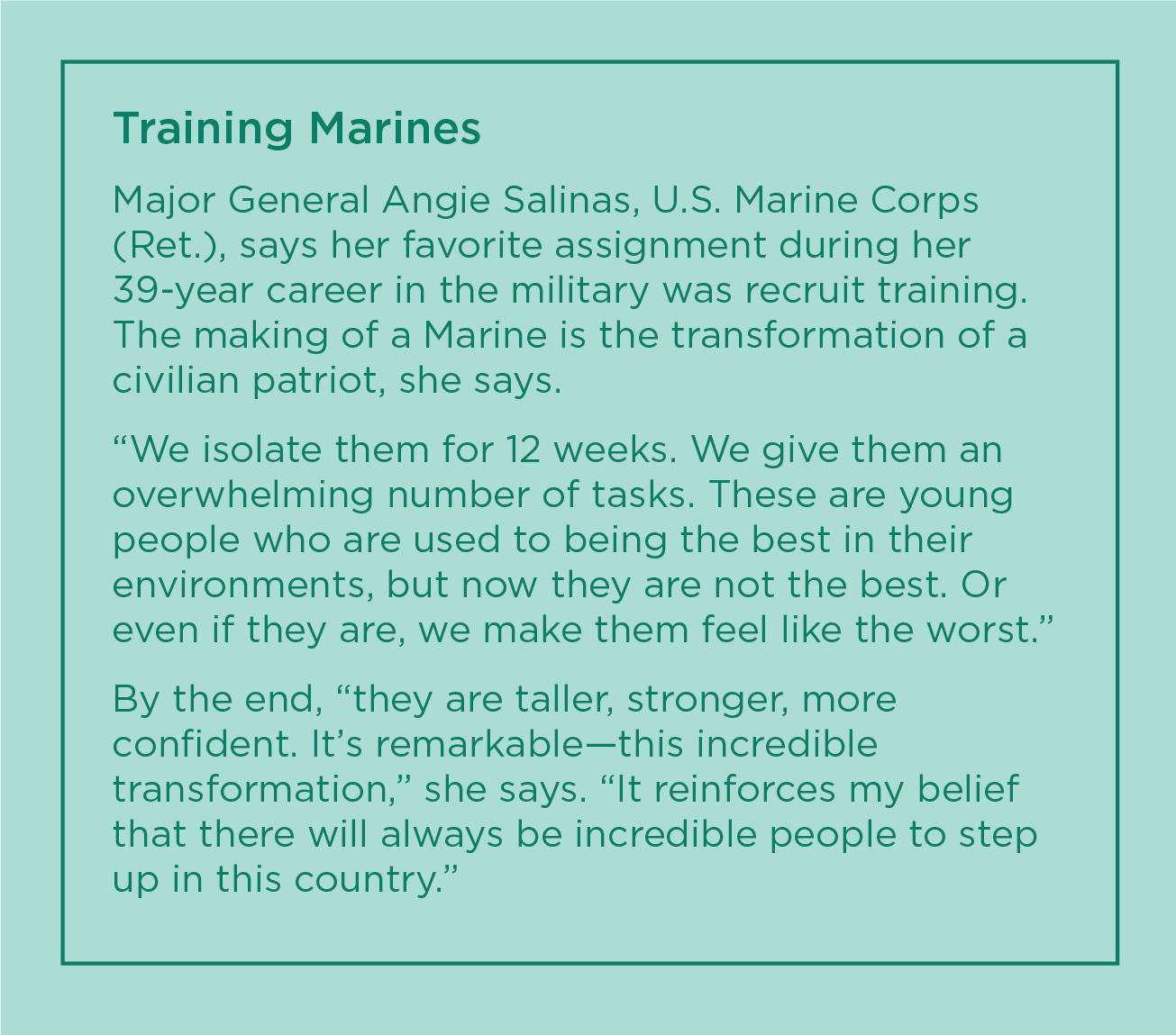

Having the Right Stuff

For her first two years in the Marines, Salinas was in the Reserves so that she could finish college. She graduated with a degree in history in 1976 and later earned a Master of Arts from the Naval War College. The Marine Corps was 98 percent male when she joined. “For many of my assignments, I was the first woman,” Salinas says.

She was the first woman to command a recruit depot and the first Hispanic woman promoted to general in 2006. She was named major general in 2010.

Her goal during her years of service: “I didn’t want to be known as a good Latina Marine or a good female Marine. I just wanted to be known as a good Marine.”

When she retired, Salinas was the highest-ranking woman in the Corps, and she is still the only Hispanic female major general. Her many military decorations include the Defense Superior Service Medal and the Navy Distinguished Service Medal.

Accepting a New Challenge

About a year and a half into her retirement from the military, Salinas stepped into the role of CEO of Girl Scouts of Southwest Texas. She felt strongly that many girls in the area would benefit from the program. “I love the mission: to build girls of courage, confidence, and character, who make the world a better place,” she says.

“About 76 percent of the members in my area are Latinas or people of color. This is a population that historically hasn’t been attracted to Girl Scouts,” she says.

The program helps prepare girls to be future leaders, she says. Many successful women today were Girl Scouts—including most of the women who have flown in space and all three women former secretaries of state: Madeleine Albright, Condoleezza Rice, and Hillary Clinton.

Girl Scout activities are built around four areas: entrepreneurship, life skills, outdoors, and STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) education. Members can earn badges on a wide range of topics, from cybersecurity to cooking new cuisines to becoming an eco-explorer.

It’s difficult to find enough adult volunteers for the troops, so Salinas and her staff have found nontraditional ways to make things work, including taking the program into schools and partnering with other nonprofit organizations. “A staff member does virtual meetings with girls who are waiting to go into a troop while we’re looking for a leader,” Salinas says.

The pandemic hurt membership, and the council is working to encourage parents to get girls into the program, she says.

Raising Money for Girl Scouts

Stepping into this job meant Salinas had to develop new skills, including learning how to raise money.

When she took control, the group was in the red. It was critical to balance the budget because people are uncomfortable giving money unless you do, Salinas says.

Every year, she must raise enough for her council to pay the staff; offer a variety of programs; provide scholarships to girls; and maintain the camp, buildings, and grounds. “Right now, I’m struggling, because if people don’t want to donate, I can’t offer some programs. I have a 236-acre camp that needs a new water tank.”

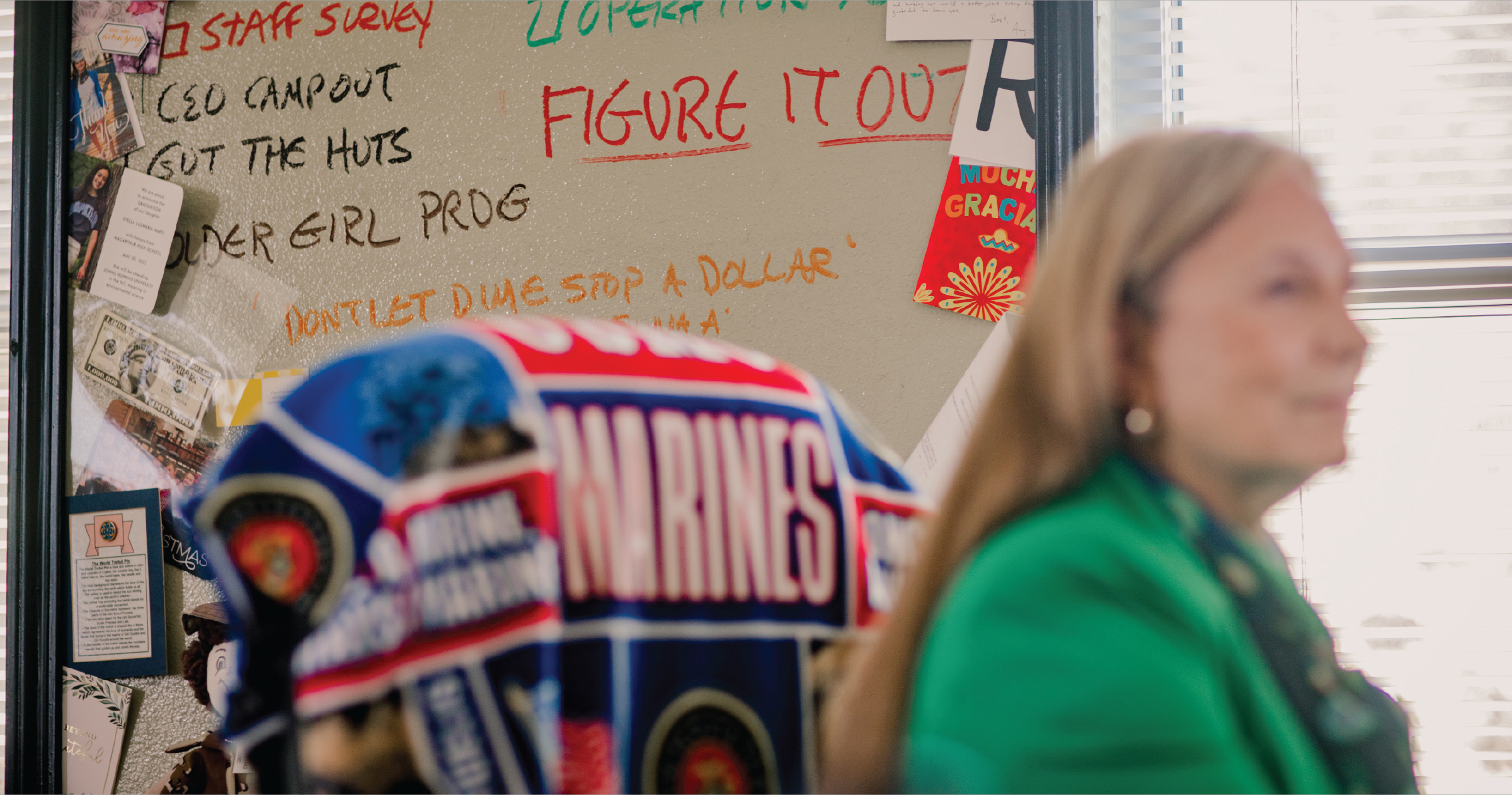

She made a mistake early in her new role that helped shape her philosophy. She met with a donor and walked away thinking she had gotten a large financial commitment, but at the second meeting, she realized she had misunderstood. “I had already put the money in the budget. Camp was in session. We had given girls scholarships.”

“I got in my car, ready to quit,” Salinas says. “I thought to myself: This is too hard. I’m a general. I’m a failure. I’m at my wit’s end. How do I go to the board and tell them that we are going to go a quarter of a million dollars in the hole?”

“But I thought about a seven-year-old Girl Scout trying to sell cookies,” she says. “She might have a goal of selling 250 boxes of cookies to help pay for a trip the troop is planning.

“That young Girl Scout may ask someone if they want to buy a box of cookies, and they say no. She asks if they would like to buy a box to give to a friend. They say no. She asks if they would like to donate a box to a military member, and they say no again. The Girl Scout says, ‘Thank you very much, and have a great day.’”

“She’s bummed, but she still has to sell 250 boxes of cookies because people are depending on her,” Salinas says.

“I thought, if that seven-year-old Girl Scout can figure it out after someone says no to her three times, I can figure it out. That’s my philosophy.”

Salinas went back to her office and wrote on the wall: “Figure it out.” The motto is still there.

Taking a lesson from that young Girl Scout, Salinas went back to the donor. “I said, ‘Listen, please blame me. I’m new. I made a mistake. I didn’t get it in writing, but I can’t solve this problem without your money. I will never ask for another penny, but please don’t punish our Girl Scouts for me not knowing what I’m doing.’”

The donor didn’t give the full amount but gave enough for Salinas to make her budget. And after a few years, the donor came back to offer financial help again.

Salinas is in awe of people “who invest in our mission.” At lunch with a donor recently, she explained her vision to turn 3.5 acres into a space with an outdoor pavilion, a camping area, ropes and an adventure area, and nature trails. When Salinas was driving home, the woman called and offered $1 million to jump-start the project.

“We had never received a donation in this amount in a non- capital campaign. I almost drove through my garage.”

Enjoying the Achievements

Salinas says she’s inspired by the girls who use their Gold Awards—the highest achievement a Girl Scout can receive—or use other projects to help fix a problem in their communities or make a lasting change in their world. One girl worked with the state legislature on a bill to combat cyberbullying; another created a magnet with medical information for senior citizens to post on their refrigerators.

One of the biggest rewards of the job is seeing how the program changes lives. One Girl Scout was introduced to aviation by a volunteer, and she eventually met an Air Force pilot who took her for a flight on a Cessna. “Later, that girl went to the United States Air Force Academy and is now flying jets for the Air Force,” Salinas says. All because of a chance meeting through Girl Scouts.

Another girl decided to pursue a degree in the environmental sciences after her experiences at camp. “These are women who, in the next 10 years, are going to be incredible movers and shakers. They already are.”

Saluting Her Work

People who know Salinas are impressed with her dedication and management style. She’s the perfect person for the job because of her leadership skills, communication ability, and likeability, says Suzanne Goudge, a banker and a strong supporter of the Girl Scouts. “She’s real and approachable. She is humble.”

If Salinas is walking by a young Girl Scout, she immediately stops, gets down on her level, and talks to her, Goudge says. “She is a role model who enables the girls to see that they can be whatever they want to be, no matter where they start from.”

CAPTRUST Senior Director Teri Grubb, one of the Girl Scouts of Southwest Texas’s board members, agrees. “She does everything she can to make things better for these young girls. She looks for ways to offer them new opportunities and pathways to education and future careers. She lives and breathes the mission through and through.”

Her management style is inclusive, Grubb says. “When we are talking about ideas, everybody’s voice and vote counts. You don’t see that in all leaders.”

When it comes to her legacy in this role, Salinas says it’s not about her.

“Our council is celebrating 100 years in 2024. I’m envisioning a stadium filled with people from our community taking a pledge to commit to ensuring our Girl Scouts are here for the next 100 years. That should be everyone’s legacy,” she says.

The organization teaches its members to leave a place better than it was when they found it. Salinas wants to do the same. “I hope that people say that I was a good Marine and that I was a good Girl Scout.”