-

Solutions

- Solutions

- Individuals

-

Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Corporations

- Educational Institutions

- Healthcare Organizations

- Nonprofits

- Government Entities

- Endowments & Foundations

- See All Solutions

Comprehensive wealth planning and investment advice, tailored to your unique needs and goals.Investment advisory and co-fiduciary services that help you deliver more effective total retirement solutions.CAPTRUST provides investment, fiduciary, and risk management services for nonprofit organizations. -

About Us

- About Us

- Our People

- Our Story

- Learn About CAPTRUST

-

Locations

-

Resources

- Resources

- Articles

- Podcasts

- Videos

- Webinars

- See All Resources

With increasing and varied litigation, it has become more difficult for retirement plan fiduciaries to manage their risk. Best practices have become more challenging as plaintiffs’ attorneys find new ways to sue plan sponsors, while at the same time fiduciary liability insurance has become less comprehensive and more expensive.

What’s a fiduciary to do? Join CAPTRUST and some of the leading experts in the field of fiduciary risk management as we provide practical solutions to these problems and help plan sponsors become more confident in managing their fiduciary risk.

Join us on Wednesday, August 21 from 4:00 to 5:00 p.m. ET.

Additional Resources

The Importance of Fiduciary Training

2024 Fiduciary Training Series, Part 1: Roles and Responsibilities

2024 Fiduciary Training Series, Part 2: Plan Governance

Rivers offer another example. Narrow and broad rivers can convey the same amount of water, depending on their depth and flow. One river, which delivers nearly 20 percent of the world’s freshwater to the ocean, varies in width from less than one mile to more than 30 miles across. Its name, relevant to today’s market discussion, is the Amazon.

So far this year, leadership in the U.S. stock market has been extraordinarily narrow, with five mega-cap technology powerhouses—Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, and NVIDIA—delivering a full 60 percent of S&P 500 Index returns. Without this quintet, the index would have shown negative returns for the second quarter.

Most market watchers view such a narrow market as less healthy and resilient than more broad-based participation. Yet this small group of stocks has driven markets relentlessly higher.

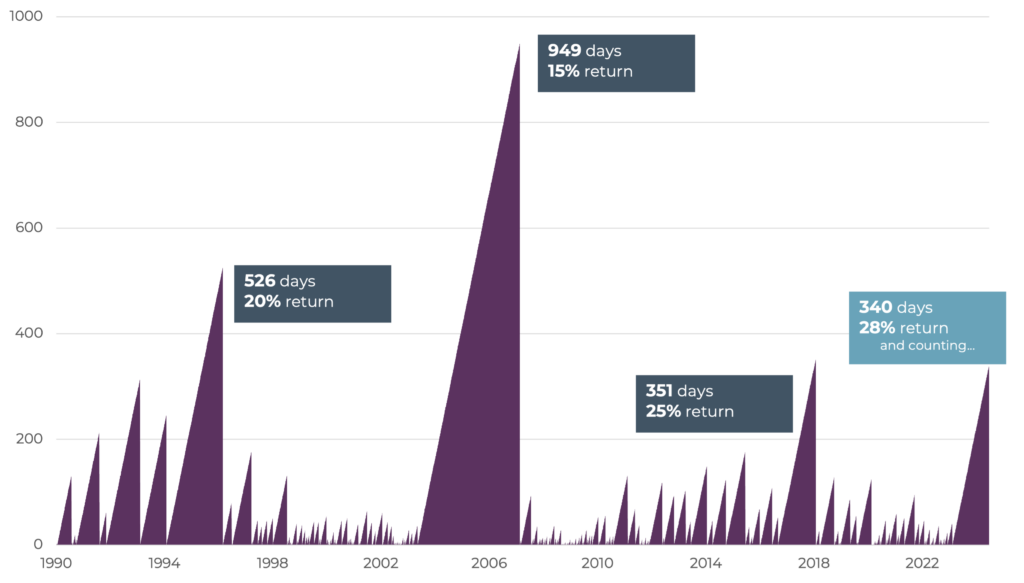

Since February of last year, the S&P 500 has increased by nearly 40 percent without a single daily decline of 2 percent or greater. As shown in Figure One, this represents the fourth longest period without a 2 percent decline since 1990, and the current period has a higher annualized return than the other three.

Figure One: Trading Days Without a 2 Percent or Greater Decline (1990–June 2024)

Sources: Morningstar Direct, CAPTRUST Research. Percentage returns are annualized.

Market Rewind: Second Quarter 2024

April began on rocky footing as inflation data came in hotter than expected, quelling hopes for a second-quarter Federal Reserve interest rate cut. That same month, markets also digested escalating Middle East tensions after a volley of attacks between Iran and Israel, causing volatility in stock and energy prices.

However, the markets quickly recovered, as these tensions calmed and a string of data releases suggested the U.S. labor market, consumer spending, and overall economic activity were cooling in an orderly fashion, while corporate earnings remained solid.

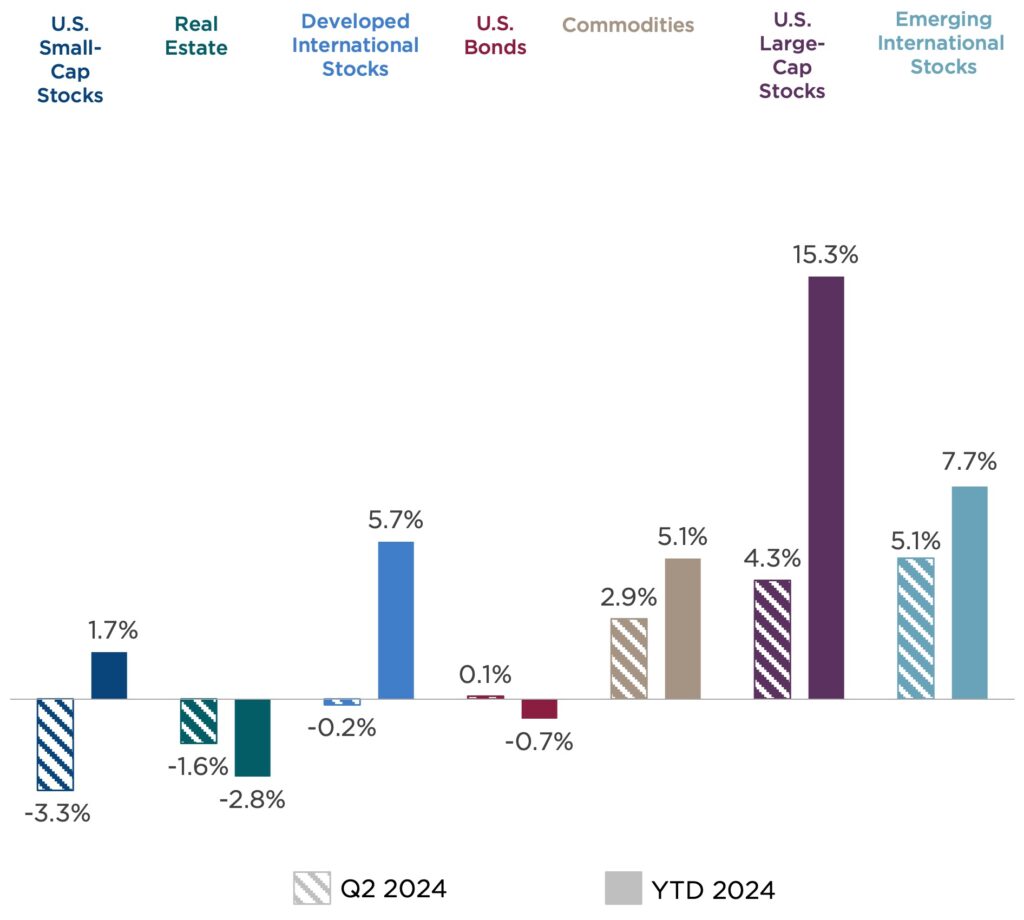

U.S. large-cap stocks continued their early-year momentum, with the S&P 500 delivering returns of 4.3 percent and finishing the quarter just shy of a new all-time high. Overall results masked more disparate activity beneath the surface, with more than half of the 11 S&P 500 sectors posting negative returns for the period.

In contrast, small-cap stocks struggled to a 3.3 percent loss as larger companies continued to capture the lion’s share of market gains. Despite continued economic strength, smaller companies have lagged under higher interest rates, due to their tendency to carry higher levels of debt.

Figure Two: Second Quarter 2024 Market Recap

Asset class returns are represented by the following indexes: Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (U.S. bonds), S&P 500 Index (U.S. large-cap stocks), Russell 2000® (U.S. small-cap stocks), MSCI EAFE Index (international developed market stocks), MSCI Emerging Market Index (international emerging market stocks), Dow Jones U.S. Real Estate Index (real estate), and Bloomberg Commodity Index (commodities).

Outside the U.S., performance varied by region. Currency weakness weighed on Japan, and political uncertainty hampered Europe. Emerging market stocks added to their first-quarter gains with a 5.1 percent return in the second quarter. Performance was buoyed by market-friendly actions from Chinese authorities to support the nation’s struggling real estate sector, plus continued strong results from the Taiwanese semiconductor sector.

Interest rate–sensitive segments of the market underperformed, as the yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond climbed from 4.2 to 4.4 percent. Core U.S. bonds sold off in the final week under pressure from rising interest rates, to finish the quarter essentially flat. Credit spreads remained stable for the period. Real estate showed a modest loss of 1.6 percent.

Commodities were volatile as energy prices, particularly oil prices, experienced swings due to geopolitical tensions and production adjustments by major exporters. Precious and industrial metal prices advanced, especially gold, silver, and copper, while agricultural commodities lagged.

Broad Perspectives on Narrow Market Leadership

The narrowness or breadth of various economic and market conditions can provide important clues to their strength or fragility. Today, we see narrow conditions not just within the stock market but also in key areas such as consumer behavior, inflation drivers, and election outcomes. These factors carry important implications for the future direction of the economy and markets.

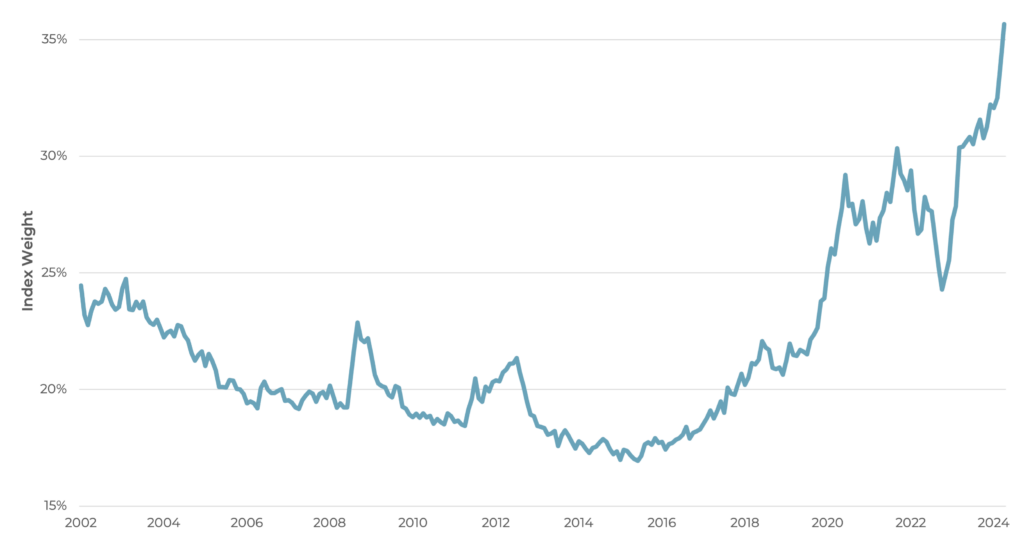

When a smaller group of companies drives overall index performance, that index can become increasingly top heavy. As shown in Figure Three, the 10 largest companies in the S&P 500 now represent 36 percent of the index—the highest degree of concentration since the 1970s.

Figure Three: Total Weight of the Top 10 Stocks in the S&P 500 Index

Sources: Morningstar Direct, CAPTRUST Research

To put this in perspective, Microsoft—the highest-weighted stock in the S&P 500—currently has a market capitalization of more than $3.4 trillion, which is nearly 100 times larger than that of the median stock. The level of concentration in these top stocks has now reached a multi-decade record, far higher than what the markets witnessed during the height of the dot-com bubble.

Optimists argue that this degree of concentration should not be concerning, because it demonstrates the exceptional growth, durability, and sheer earnings power of these few companies. It also reflects their ability to navigate the high interest rates, inflationary pressures, and geopolitical uncertainty of the past few years better than their peers.

However, others view this degree of concentration as a sign of market vulnerability. The combination of a narrow market and high valuations increases concerns about the potential for a correction (a decline of 10 percent or more from recent highs) if these companies fail to deliver on lofty earnings growth expectations.

Although analysts now expect earnings growth will stretch across a much larger swath of the equity markets in the second half of 2024 and in 2025, any such expansion of market strength is likely to depend on lower interest rates.

Narrowing Consumer Strength

Consumer spending is the single largest component of U.S. economic activity. The consumer’s ability and willingness to spend during and after the COVID-19 pandemic has, in large measure, prevented a significant economic slowdown, despite high inflation and restrictive monetary policy. Now, it seems consumers could be losing steam.

Recent retail sales data suggests cooling spending activity. Inflation-adjusted retail sales for the April to May period fell by 1.2 percent compared to the first quarter of 2024, with spending on goods showing particular weakness. Other discretionary categories such as food services and drinking places have fallen for three of the past five months. Despite positive movement in some areas, such as automotive-related sales, the overall picture points toward more cautious consumer behavior. [1]

Another place where consumer stresses are becoming evident is in credit utilization. Total credit card balances have now eclipsed $1.1 trillion, while the average interest rates for accounts carrying a balance have risen above 22 percent. Nearly one in five credit card users have maxed out their available credit. Delinquency rates for both auto loans and credit cards have surpassed their 2019 levels by 15 percent and 28 percent, respectively. [2]

A likely contributor to credit card stress is the depletion of savings accumulated during the pandemic. One frequently cited pillar of consumer strength over the past four years is the surplus of savings built up throughout the pandemic, partly due to substantial government stimulus payments.

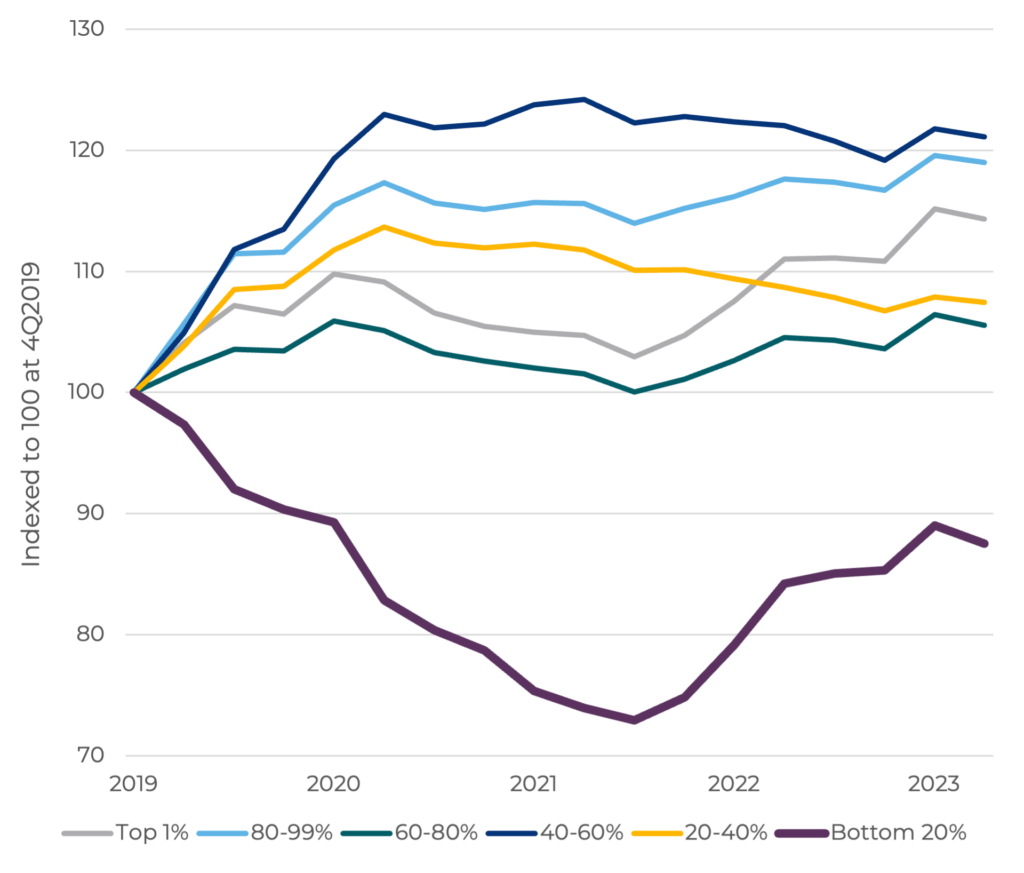

Now, this savings cushion is narrowing. As usual, the greatest stress is being felt by those with the lowest incomes, as household budgets are squeezed by rising prices, high interest rates, and climbing rent payments. Levels of consumer sentiment for the lowest third of earners is far below that of middle and high earners. And, as shown in Figure Four, while higher-income households continue to maintain a cushion of excess savings, the level of inflation-adjusted liquid assets for the bottom 20 percent of earners has deteriorated since 2019. [3]

Figure Four: Changes in Real Household Liquid Assets

Sources: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, CAPTRUST Research

Despite these warning signs, the strong labor market remains a powerful tailwind for consumer activity. The ability to find and keep a job that pays wages that grow faster than inflation plays a pivotal role in supporting consumer confidence and activity.

While the unemployment rate rose slightly in June, its level of 4.1 percent is still far below the 40-year average of 5.8 percent. The labor force participation rate among prime-age workers (those between ages 25 and 54) has also risen to a two-decade high, helping offset the surge of early retirements witnessed during the pandemic. And the number of job vacancies per unemployed worker remains at 1.2, matching its pre-pandemic level. [4]

Narrowing Inflation Drivers

Following 2022’s inflation spike, which saw the consumer price index (CPI) rise to a four-decade high of 9 percent, there has been a substantial cooling in price pressures. In May, inflation was lower than expected at 3.3 percent on a year-over-year basis. This was the smallest monthly gain for more than two years. Although there is still some distance to cover before reaching the Fed’s 2 percent inflation target, continuing signs of declining inflation sustain hopes that the Fed could deliver its first rate cut later this year.

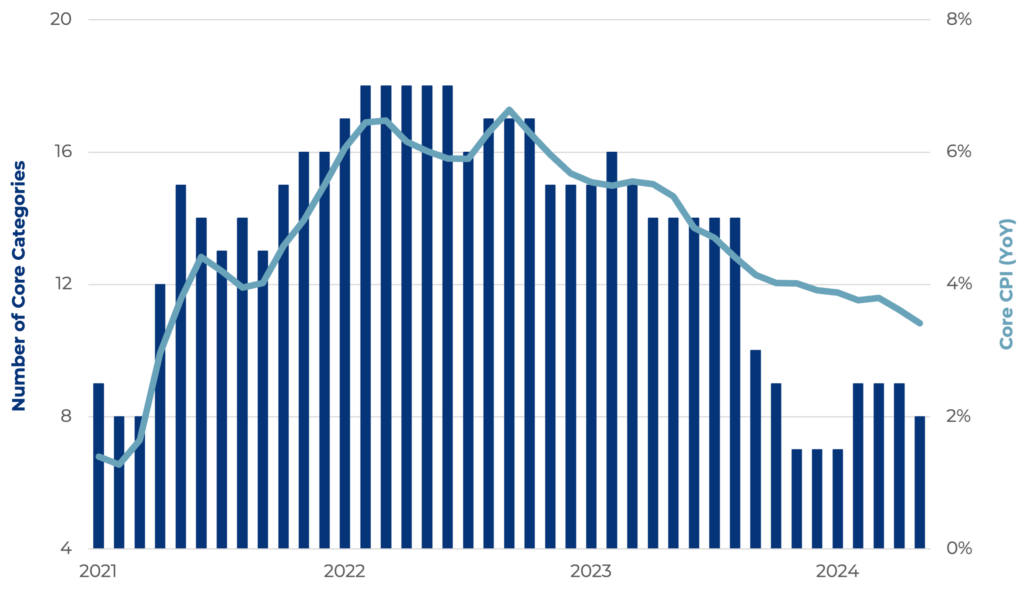

Another positive sign is that the number of categories showing more than 2 percent inflation within the basket of goods and services used to calculate CPI continues to narrow. At its peak in 2022, virtually all major categories of goods and services exceeded the Fed’s 2 percent target. As Figure Five shows, the number of categories exceeding this threshold has steadily declined since. Several essential categories, including shelter and medical care, which tend to carry higher weights within the CPI, continue to hold inflation above target. Others, including new and used vehicles and airfares, have fallen considerably. This indicates that inflation in those categories is likely due to specific factors, rather than broad-based price pressures—a positive sign that inflation is not firmly entrenched.

Figure Five: Number of Core CPI Categories with Inflation Greater than 2 Percent (Year Over Year)

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, CAPTRUST Research

Another positive sign is that the magnitude of price increases has subsided. At the peak, prices of essential items such as dairy were up more than 20 percent from the prior year. Today, the rate of change in this category has fallen to just 1 percent.

A Narrow Election

Historically, presidential election years have seen solid investment returns. This is especially true in years when an incumbent is running for reelection, as administrations are motivated to use government tools to maintain economic strength. Over the past 50 years, election years with a running incumbent have seen S&P 500 returns of more than 17 percent on average.

History also tells us that markets can thrive under any division of government. Markets performed well under both of the current presidential candidates’ previous terms.

However, rarely have the policy differences between candidates been so great—from international relations, tariffs, and deglobalization, to tax, energy, and regulatory policy. It was already shaping up to be a close and unpredictable election, even before the attempted assassination of former President Trump on July 13. This horrific event will change the dynamic of the race in unpredictable ways, and there will likely be many more twists and turns between now and November.

Control of Congress is also paramount for either party to fulfill its agenda. This is important given the significant fiscal policy imperatives on the legislative docket in 2025. The debt ceiling extension passed in June of this year is set to expire on January 1, 2025, which will require Congress to return to the negotiation table. More than $4 trillion of tax provisions are also set to expire next year, without an extension.

Regardless of who wins the presidential election, they will inherit a fraught federal budget when they take office. Due to ballooning government debt in the post-pandemic era, plus the high interest rate environment, the interest expense on federal debt has nearly doubled over the past three years.

Interest expense on government debt now exceeds defense spending as a share of the federal budget. This represents a potential risk to investors if neither candidate or party is able to enact fiscal reform. Continued deterioration of the fiscal situation could translate to higher bond market volatility due to changing supply and demand dynamics for Treasury bonds.

So far, markets have remained calm amid the dramatic events of this early election season. Although presidential election years generate abundant headlines, they typically have a more muted effect on markets. Nevertheless, given the substantive differences between the candidates’ policy priorities, it is likely that election uncertainty will eventually make its way into markets. When or if the odds of the election become clearer, industries that are connected to the policy preferences of the candidates and parties are likely to react, particularly around the energy and financial sectors.

Broad Possibilities

At this halfway point of the year, the financial markets have delivered a broad range of results—from exceptional returns for U.S. large-cap and international equities to disappointing outcomes for more interest rate–sensitive categories such as small-cap stocks, bonds, and real estate. Corporate earnings have been robust among the largest companies, but this growth must broaden to return the market to a more balanced position.

Although investing always involves uncertainty, investors prefer unknowns that they can analyze and discount. The remainder of the year will present challenges that are less fundamental in nature, and therefore perhaps more troubling to markets: the outcome of a narrow election season, the actions of Fed policymakers, the unknown impacts of emerging technology, and significant geopolitical risks.

While investors should be alert to these risks and the potential for changing conditions, they should also recognize that change often creates new opportunities.

[1] “Retail Sales Confirm Continued Consumer Spending Pullback,” The Conference Board

[2] New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, CAPTRUST Research

[3] Surveys of Consumers, University of Michigan

[4] Bureau of Labor Statistics, CAPTRUST Research

Life insurance can help financially protect your loved ones when you die. This type of policy ensures a payout will go to the person you name (your beneficiary) when you’re gone. The payout is generally tax-free.

Your beneficiary can then use your life insurance payout to cover any debts that you have left behind, like mortgages, car loans, or credit card debt. Life insurance payouts can also pay for final expenses and estate taxes or can serve as an inheritance for the beneficiary.

What Else Can Life Insurance Do?

Life insurance can provide benefits while you’re living, as well. First, it offers the peace of mind that comes from knowing your loved ones will be cared for. Also, some life insurance policies come with a cash value that you can withdraw or borrow. You can also use the cash value of the policy as collateral to apply for loans or supplement your retirement income.

There are also policies that pay out before your death if you become incapacitated or terminally ill.

Who Should You Name as a Beneficiary?

Your primary beneficiary is the person (or a corporation or legal entity) who receives the proceeds of your insurance policy. You can also name a contingent beneficiary to receive the proceeds if your primary beneficiary dies with or before you. For instance, if your primary beneficiary is your spouse, and you die together, you will need a contingent beneficiary listed on the policy. The contingent beneficiary then becomes the primary beneficiary. Another option is to name multiple beneficiaries and specify what percentage of the net death benefit each is to receive.

You should carefully consider the ramifications of your beneficiary designations to ensure that your wishes are carried out as you intend.

Generally, you can change your beneficiary at any time by signing a new designation form and sending it to your insurance company. However, if you have named someone as an irrevocable (permanent) beneficiary, you will need that person’s permission to adjust any of the policy’s provisions.

How Much Life Insurance Do You Need?

Your life insurance needs will depend on factors such as your age, marital status, the size of your family, the nature of your financial obligations, your career stage, and your goals. Your best resource for figuring this out may be a financial professional, who can assist with determining what you need—and what you can afford.

These questions can help guide you, as well:

- What immediate financial expenses (e.g., debt repayment, funeral expenses) would your family face upon your death?

- How much of your salary is devoted to current expenses and future needs?

- How long would your dependents need support if you died tomorrow?

- How much money do you want to leave for the things that matter to you, like funding your children’s education, leaving an inheritance, or gifts to charities?

Your needs will change over time, so be sure to reevaluate your coverage regularly.

Types of Life Insurance Policies

There are two basic types of life insurance: term and permanent.

Term life insurance policies provide life insurance protection for a specific period. If you die during the coverage period, your beneficiary receives the policy death benefit. If you live to the end of the term, the policy simply terminates, unless it automatically renews for a new period.

Permanent life insurance policies provide protection for your entire life, so long as you pay the premium to keep the policy in force. Premium payments are larger in the early years of the policy in order to accumulate a reserve. In later years, this accumulated reserve, known as the cash value, is used to cover the shortfall between premium payments and insurance payouts. Should the policy owner discontinue the policy, the cash value is returned to the policy owner.

Where Can You Buy Life Insurance?

Your employer may offer it through a group life insurance plan. You can also buy insurance through a licensed life insurance agent or broker, or directly from an insurance company.

Any policy that you buy is only as good as the company that issues it. Ratings services, such as AM Best, Moody’s, and Standard & Poor’s, evaluate an insurer’s financial strength. The company offering coverage should provide you with this information.

A financial advisor can help you understand which type of life insurance might be best for you, and how much coverage you should purchase. They may also be able to provide a list of life insurance agents or brokers in your area. For help getting started, call CAPTRUST.

What is a Trust?

A trust is a legal entity that holds assets for the benefit of another. Think of a trust as a safe that can be loaded with anything you choose. You get to decide who can open that safe, and when.

There are generally three parties in a trust arrangement:

- The grantor (also called a settlor): This is the person who creates and funds the trust.

- The beneficiary: This is the person or people who receive benefits from the trust, such as income or the right to use a home. These individuals have what is called an equitable title to trust property.

- The trustee: This is the person or people who hold legal title to trust property, administer the trust, and have a duty to act in the best interest of the beneficiary.

You create a trust by executing a legal document called a trust agreement. The trust agreement names the beneficiary and the trustee. It also contains instructions about what benefits the beneficiary will receive, what the trustee’s duties are, and when the trust will end, among other things.

Potential Advantages

A trust can:

- Help reduce estate taxes;

- Shield assets from potential creditors;

- Avoid the expense and delay of probate*;

- Preserve assets for your children until they are grown, in case you die while they are still minors;

- Create a pool of investments that can be managed by professional money managers;

- Set up a fund for your own support in the event of incapacity;

- Shift part of your income tax burden to beneficiaries in lower tax brackets; and

- Provide benefits for charity.

*Note: Probate is the court-supervised process of settling a deceased person’s estate. Probate can be a complicated process and often takes six to 18 months to complete.

Potential Considerations

Trusts also have potential disadvantages. First, there are costs associated with setting up and maintaining one. These may include trustee fees, professional fees, and filing fees. It’s also important to know that, depending on the type of trust you choose, you may give up some control over the assets in the trust. Also, maintaining the trust and complying with recording and notice requirements can take considerable time. Lastly, income generated by trust assets and not distributed to trust beneficiaries may be taxed at a higher income tax rate than your individual rate.

Types of Trusts

There are many types of trusts, the most basic being revocable and irrevocable. The type of trust you should use will depend on what you’re trying to accomplish.

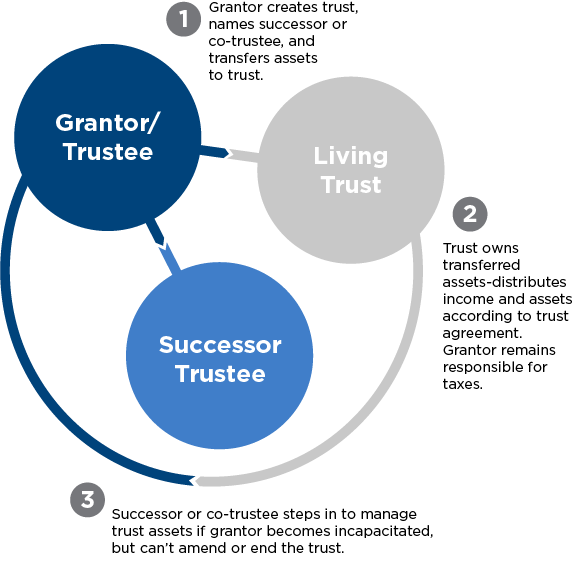

Revocable Trusts

A revocable trust, also called a living trust, is a trust that you create while you’re alive. This type of trust:

- Avoids probate. Unlike property that passes to heirs by your will, property that passes by a living trust is not subject to probate, avoiding the delay of property transfers to your heirs and keeping matters private.

- Maintains control. You can change the beneficiary, the trustee, and any of the trust terms as you wish. You can also move property in or out of the trust, or even end the trust and get your property back at any time.

- Protects against incapacity. If, because of an illness or injury, you can no longer handle your financial affairs, a successor trustee can step in and manage the trust property for you while you recover. In the absence of a living trust or other arrangement, your family may have to ask the court to appoint a guardian to manage your property.

A revocable trust can also continue after your death. You can direct the trustee to hold trust property until the beneficiary reaches a certain age or gets married, for instance.

Despite these benefits, revocable trusts have some drawbacks. A revocable trust does not:

- Remove assets from your estate for tax purposes. Although these assets would avoid probate, they are still owned by the grantor and would be included in the gross estate.

- Provide creditor protection.

- Provide tax advantages.

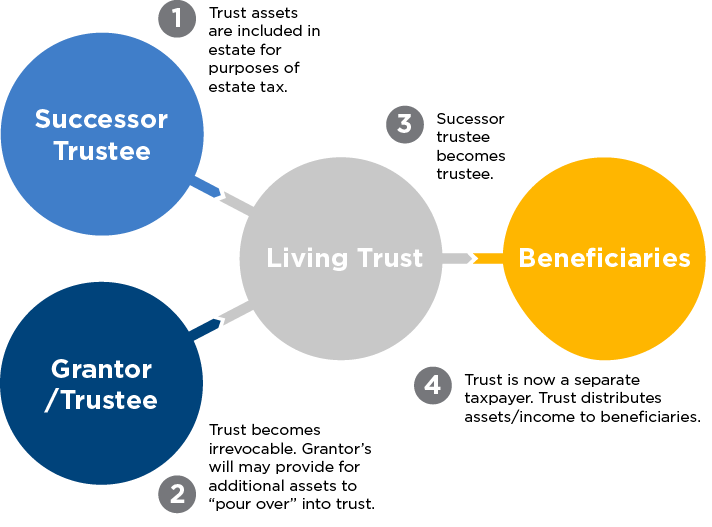

Irrevocable Trusts

An irrevocable trust is a type of trust where, once established, the grantor generally can’t change, revoke, alter, or modify the trust. These trusts are considered separate entities, can remove assets from an individual’s estate, and may be subject to their own tax filing. There are many types of irrevocable trusts depending on what you want to fund it with, your intended beneficiary, and the access required. Irrevocable trusts can be established and funded during life or at death, depending on your goals for the trust.

An irrevocable trust:

- Avoids probate. Assets owned by an irrevocable trust are distributed subject to the terms of the trust outside of the probate process.

- Exists outside of your gross estate. For those with a taxable estate, funding an irrevocable trust during life can remove those assets and their growth from your taxable estate.

- Provides creditor protection. Assets are generally considered no longer in the control of the grantor and would generally not be subject to creditors. Provisions can be added to protect assets from the beneficiaries’ creditors as well.

- Provides control over distributions. Trust provisions determine when and how trust beneficiaries receive assets from the trust.

As the name implies, an irrevocable trust cannot be revoked. Although some changes can be made depending on trust rules, the funding of these trusts is generally permanent and irreversible.

Funding a Trust

You can put almost any kind of asset into a trust, including cash, stocks, bonds, insurance policies, real estate, and artwork. The assets you choose to put in a trust will depend largely on your goals. For example, if you want the trust to generate income, you could put income-producing assets, such as bonds, in your trust. If you want your trust to create a fund that can be used to pay estate taxes after your death or to provide for your family when you die, you might fund the trust with a life insurance policy.

Since an irrevocable trust is a separate entity, gifting rules would apply, and the transfer may be subject to gift tax at the time it is funded.

For help deciding which type of trust might fit your needs and goals, call CAPTRUST.

This is a true story, and more common than you might expect.

“Even seasoned nonprofits can easily become preoccupied with the sort of day-to-day challenges that impact the organization’s operations and not give enough focus to planning and bigger picture needs,” says Heather Shanahan, CAPTRUST senior director of endowments and foundations.

In the hustle and bustle of putting out small fires, it’s not unusual for leaders to get stuck in short-term survival mode and neglect some longer-term strategic issues, like succession planning. “In these situations, where hasty decisions are made during leadership transitions, sometimes even a good hire won’t stay.”

Certainly, nonprofit executives must address immediate issues, including fundraising, allocating grants, managing volunteers, recruiting and retaining staff, engaging board members, and adapting programs to changing needs, to name a few. But they should also carve out some capacity to address strategic issues like succession planning. Failure to do so may leave them vulnerable to leadership gaps and potential disruptions in their mission-driven work.

On some level, this is true for all organizations, but nonprofits are especially at risk because they often rely more heavily than for-profit organizations on the character, network, and reputation of their leaders to attract funding, partnerships, and volunteers. Abrupt changes in leadership can destabilize operations. They may also create uncertainty about the organization’s direction and impact, potentially eroding trust and support.

“Succession planning is about identifying risks and developing leaders to ensure continuity of both internal operations and the external perception of the organization,” says Heidi Spencer, a CAPTRUST senior financial advisor who specializes in helping religious organizations. “In the context of endowment or foundation boards and committees, succession planning means being prepared for both planned and unexpected transitions in key leadership roles.”

But succession planning goes beyond simply filling vacant positions. It means identifying critical roles and competencies needed for the organization’s future success, then developing a pipeline of individuals who could step into those roles. By identifying potential leaders and nurturing their growth over time, the organization can also ensure a smoother transfer of knowledge and responsibilities.

Effective governance requires nonprofit executives and board members to look beyond their current composition and consider the future needs of the organization. “For instance, if current leadership demographics don’t match the demographics of the community, succession planning can help,” says Spencer. “If leaders and board members are looking around and thinking ‘we need more young people,’ or ‘we need more people of color,’ the succession-planning process can be an opportunity to find those future leaders, grow their skills, and start handing over the knowledge they need to be successful.”

Getting Started

A comprehensive succession planning process begins by identifying the critical roles that may need to be transitioned in coming years. “I tell leaders to start by taking an inventory of their organization’s leadership positions, including board officers, committee chairs, senior leadership, and key staff roles,” says Shanahan. “From there, assess each role’s impact on the organization’s operations, and prioritize your focus based on their criticality and the likelihood of near-term vacancies.”

“Start with your most urgent issues,” says Shanahan. “Are there pending retirements, expected departures, or at-risk colleagues in critical roles? Do you want to limit your focus to the executive team, or go deeper into the organization?”

Once you’ve answered these questions, you can better understand the organization’s specific succession risks and start developing talent to mitigate them. Try to provide multiple leadership development opportunities, such as committee assignments, special projects, mentorship programs, or training sessions.

Along the way, you’ll want to develop and document job descriptions and competency requirements for each key position and establish a regular review process to make sure the thinking embedded in the plan remains current.

A comprehensive succession plan should address both orderly, long-term succession—like planned retirements—and unexpected emergencies, and provide scenarios for what-if exercises. The more you engage with all possible scenarios, the better you can manage them if they arise.

Ideas into Action

“Creating a succession plan is a comprehensive process that, by necessity, involves multiple steps and stakeholders,” says Spencer. “Leaders want to get it right, because they understand the impact it will have on the people, the organization, and the mission, and that takes time and work. But it is absolutely worthwhile.”

While input should be gathered from various stakeholders, the most important primary decision-makers will be board members and current executives. Throughout the succession planning process, boards should stay focused on mission alignment and long-term organizational needs. They will also hold final responsibility for approving the succession plan, especially for the chief executive officer or executive director position. Current executives should also give input on mission alignment but will be especially helpful in identifying internal candidates and evaluating operational skills.

The decision-making process can vary based on the organization’s governance structure, but it’s crucial to have roles and responsibilities defined from the outset. “The board should be involved throughout the process—not just at the approval stage—to ensure the plan aligns with the organization’s long-term vision and goals,” says Shanahan.

The time needed to create a succession plan will vary based on the organization’s size, complexity, and current state of preparedness. It might take from three to six months for a small organization with a simple structure. For larger, more complex organizations, one to two years is a more reasonable time frame.

Strategic Governance

Remember, while creating a formal plan is important, the most effective succession plan is an ongoing, dynamic process integrated into the organization’s overall strategic plan and governance and aligned with its culture, goals, and mission.

“Your succession-planning process and resulting plan should support and advance the organization’s strategic objectives,” says Shanahan. For example, does it promote cultural goals like developing internal candidates? Does it demonstrate the organization’s commitment to transparency and openness?

Another aspect of integrating succession planning into nonprofit governance is in how and when you engage stakeholders. As a best practice, succession planning should be a regular board agenda item, with board members identifying and mentoring potential leaders on a predictable schedule.

While the plan is a work in progress, it’s also a good idea to seek input from major donors and community partners. “Keeping them informed about succession-planning efforts will build their confidence in the organization’s future, stability, and long-term impact,” says Shanahan. “While they may not be decision-makers, their experiences may provide helpful insights, and they sometimes have resources that you can leverage in planning.”

“Your legal, tax, and financial advisors may also be able to help,” says Spencer. In her role as a financial advisor, Spencer says she has helped many clients with succession planning. “Sometimes this means helping with knowledge transfer on investment strategies. Other times, it means helping them find candidates for senior roles, or simply sharing best practices and peer insights from our annual Endowment and Foundation Survey.”

Once the plan is formulated, documented, and socialized, don’t let it just sit on the shelf. Keep the momentum going. One idea is to create a succession-focused committee at the board level to continue to refine the plan, update it as needed, and gather feedback from stakeholders. “Succession is also an excellent topic for a deep dive at least once a year or a board retreat with a focus on long-term leadership needs and development,” says Shanahan.

Another good idea to benchmark your succession-planning practices against peer organizations and industry best practices. “This is something we help with often,” says Spencer. “The breadth of our client base means that we have access to leaders in all nonprofit sectors, including community foundations, religious organizations, zoos, the arts, medical research, private foundations, you name it.”

Succession planning is a critical component of good governance for endowments and foundations. While it may not seem as urgent as day-to-day operational issues, it is critically important. Implementing a sound plan requires commitment, time, and resources. However, this investment pays dividends in terms of organizational stability, leadership quality, and sustained impact.

As stewards of their organizations’ missions, board members and nonprofit leaders have a responsibility to look beyond their tenures and prepare for the future. By integrating succession planning into governance frameworks, endowments and foundations can build resilience, enhance donor confidence, and ensure that their important work continues uninterrupted.

When SECURE 2.0 passed in December 2022, much of the initial focus surrounded its mandatory provisions, some of which went into effect almost immediately. Plan sponsors and their recordkeeping partners had to react quickly. Now, they’re thinking about what’s next.

The Big Picture

One of the SECURE 2.0’s primary goals is to tackle the most common reasons employees choose not to participate in their employer-sponsored retirement plans. These include a lack of awareness about benefits, plan uses and advantages, and the sheer complexity of most retirement savings plans.

But perhaps the biggest reason employees don’t participate is that many feel they simply can’t afford to. As Pew Charitable Trusts reports, a full 43.5 percent of full-time workers who don’t participate in their employer’s plans cite affordability as the primary reason.

“If you can’t meet your financial obligations now, it’s almost impossible to think about what your finances could look like in the future,” says Chris Whitlow, head of CAPTRUST at Work, the firm’s employee-focused financial wellness solution. “SECURE 2.0 tries to help solve this challenge for people in all different career stages.”

Retirement as One Part of Financial Wellness

Not surprisingly, the act contains multiple retirement-centered provisions directed at employees in the final decade of their careers, but there are also provisions designed to help people in early and mid-career stages. “The overall effect is that SECURE 2.0 reframes retirement as one piece of each person’s bigger financial wellness picture,” says Whitlow.

As an example, Whitlow points to emergency savings accounts. These accounts provide a financial buffer for unexpected expenses, reducing the need for employees to dip into their retirement savings prematurely. “Having enough money set aside for potential emergencies is one of the biggest financial insecurities that often prevents employees from committing to long-term savings,” he says.

SECURE 2.0 permits employers to offer an emergency savings distribution option of $1,000 per year that can be repaid to the plan over a three-year period, with participants self-certifying the need for a distribution. Having an emergency savings option enhances employees’ ability to access money when it’s truly necessary but could increase plan leakage over time.

For that reason, and because of the heavy work involved in integrating emergency savings funds into plan designs, some sponsors are providing emergency savings outside of their retirement plans, says Mike Webb, CAPTRUST senior manager of plan consulting. “It’s another way of encouraging overall savings, and a savings mindset.”

“Having an emergency savings account reduces financial stress,” says Webb. “When you know you have enough money to deal with unexpected events, then you’re more likely to save for retirement. You’re more likely to participate in your employer’s retirement plan.”

However, for plan sponsors interested in offering emergency savings accounts, there are other ways to achieve the same goal, says Lisa Keith, CAPTRUST senior manager of plan consulting. “Alternate plan design options, like after-tax contributions, can help with savings without the complexity of emergency savings provisions.”

Regardless of how plan sponsors decide to bring these provisions to life, the point is that they are discussing employee benefits in new and bigger ways. “SECURE 2.0 encourages employers to consider the broader financial well-being of their employees, beyond retirement readiness,” says Whitlow. “It helps change the way people think about saving and about their retirement plans.”

Shifting the Mindset around Saving and Spending

This shift is necessary to encourage long-term savings among employees. It also may help reduce financial stress.

The integration of student loan matching is a prime example. “This is a game-changer for young professionals burdened with debt,” says Whitlow. An employee who is currently repaying student loans might find it challenging to allocate funds toward their retirement savings, especially when retirement is three or four decades away.

Through student loan repayment matching, employers can balance an employee’s student loan repayments with contributions to their retirement plan, thereby facilitating both debt repayment and retirement savings simultaneously. Provisions like this allow the employee to see an immediate benefit while also securing their financial future. This, in turn, can help improve overall financial well-being.

Over time, plan sponsors may find that SECURE 2.0’s focus on financial wellness leads to higher employee satisfaction and retention. “When employees know their employers are truly invested in their financial well-being, it fosters a sense of loyalty and commitment,” says Keith.

Putting Savings on Autopilot

Automatic enrollment is another feature that can help combat inertia and ensure employees start saving early in their careers. Beginning in 2025, SECURE 2.0 requires new 401(k) and 403(b) plans (and plan sponsors who newly adopt a multiemployer plan, or MEP) to include automatic enrollment with a minimum default rate of 3 percent, up to a maximum of 10 percent.

Although auto-enrollment is not required for existing plans, it is highly recommended and has been proven to substantially improve retirement readiness. This is because it removes the burden of actively opting into the plan.

Also, when employees are automatically enrolled, the vast majority will choose to stay. Research from Vanguard shows that auto-enrollment can increase participation by 30 percent or more, with more than three-quarters of plan participants remaining exclusively invested in the default fund three years later.

“Auto-enrollment is key to improving saving behavior, especially for younger employees,” says Keith. “I bet my own sons wouldn’t have money in their 401(k) plans if it weren’t for automatic enrollment.”

When coupled with automatic escalation, auto-enrollment can also ensure that contributions increase gradually over time, helping employees save more as their earnings grow. “We used to see a lot of employers starting auto-enrollment at 3 percent, but now we’re seeing default rates increase to around 6 percent,” says Keith. “Truthfully, I don’t think 3 percent was ever really adequate. It was a good start, but it’s not enough anymore. Continuing to auto-escalate helps people contribute more as they earn more, and it trains their brains to prioritize saving.”

By changing how employees think about and engage in saving, the SECURE 2.0 Act encourages a more proactive and positive approach to financial planning.

Challenges in Integrating SECURE 2.0 Provisions

Despite the potential benefits of the act, plan sponsors face significant challenges integrating its provisions to existing retirement plans. The complexity of new features and the need for administrative adjustments can be daunting. “But from a participant’s standpoint, many of these provisions are worth the work,” says Keith.

One of the main challenges is the effort required to update plan designs and administrative systems. “The operational complexities of offering things like emergency savings accounts and student loan matching are not insignificant,” says Webb. “Right now, plan sponsors are laying out years-long roadmaps to determine which of the optional provisions they’re going to offer, and when. They’re working with vendors and recordkeepers to build these things out as fast as possible, but it’s going to take time.”

Another challenge is ensuring clear communication and guidance to participants about new features. “Employees can’t use a feature if they don’t know it exists, don’t understand its benefits, or simply don’t know how to get started,” says Whitlow.

To facilitate the integration of these provisions, plan sponsors must invest in clear, continued education and communication. “Ongoing training is essential to ensure that plan administrators and employees understand the benefits and logistics of the new provisions,” says Keith.

Plan sponsors should also consider leveraging technology to streamline the implementation process. Advanced recordkeeping and automated systems can significantly reduce the administrative burden and improve the accuracy and efficiency of managing new features.

Furthermore, collaboration with service providers and consultants can help plan sponsors navigate the complexities of SECURE 2.0 and any future legislation or regulation.

In addition to technological and consultative support, plan sponsors should actively seek feedback from their employees and plan participants to ensure that plan design changes and new features meet their needs and expectations. “Regularly soliciting feedback from employees can help identify any issues early on and ensure the plan design is aligned with participant needs,” says Webb.

By reframing retirement readiness as one part of overall financial well-being, SECURE 2.0 offers the opportunity for plan sponsors to provide employees with a balance of long-term planning and an enhanced ability to meet near-term financial needs. Ultimately, the success of integrating these provisions depends on the commitment of plan sponsors to embrace this new model of financial wellness programs.

An annual tradition, this year’s survey expands on questions and techniques from previous years’ editions. As always, its intention is to help nonprofit leaders understand what others in the space are doing, and why.

Our goal is to arm nonprofit decisionmakers with clear and actionable information that can help them make a positive impact. By understanding peer thought processes, nonprofit organizations can tap into the collective wisdom of the sector to inform their own decision-making.

The survey is open now and will close on August 1, 2024.

To thank you for your participation, 501(c)(3) organizations that fully complete the survey on or before July 5, 2024, will have their names placed in a drawing for a $3,000 donation.

Job markets may rise and fall, but attracting and retaining top talent remains essential to the long-term success of any organization. “Employees are our most valuable assets,” says Christopher Whitlow, head of CAPTRUST at Work. “Companies are built on the capital of the people who create the ideas.”

“When we lose that talent, the effect is far-reaching, from the time and cost of recruiting someone new to the loss of business-critical expertise when longtime workers leave,” says Whitlow.

Employees who feel happy at work tend to be more productive, innovative, and loyal. These effects can lead to happier customers and clients, which can, in turn, lead to greater business success. To keep more employees satisfied and less likely to begin job-searching, a good place to start is with your financial wellness benefits. But these days, financial wellness means more than simply teaching people how to budget.

Wealth-Building is Loyalty-Building

“One of the most powerful ways to attract and retain employees is to generate wealth-building opportunities for them that help keep them grounded in their daily jobs,” says Whitlow. “As an employer, if you’re looking at your workforce, and people are generally not in that space where they’re creating their own wealth, then you might want to think about how you can help them overcome their challenges, help level the playing field for them,” says Whitlow.

This means creating myriad opportunities that work for both your organization and your unique employee population, from tackling student loan debt to assisting highly compensated employees who might not be able to maximize their savings in a qualified retirement plan.

What is key is to understand the unique makeup of your employee base. Each organization is distinct, so benefits should be as well. “To be highly effective and highly efficient, we have to stop picking financial benefits and financial wellness programs off the shelf in a one-size-fits-all approach,” says Whitlow.

Surveys are a great way to learn which benefits employees actually want. To feel confident you’re offering the best financial benefits for a wide range of employees, start by asking them about the financial obstacles they’re currently facing and how they would rate their own financial health or financial confidence.

Ask First

“Don’t be afraid to ask open-ended questions,” says Jennifer Doss, CAPTRUST defined contribution practice leader. “If you let people describe their own challenges and goals, you’ll have more information about their financial situation and their needs.”

To make sure everyone feels represented, Whitlow suggests bringing your survey to your company’s employee resource groups, or ERGs. He suggests asking ERG leaders, “Can you look over these survey questions and tell us how you might change them to be more inclusive?”

Share the results of your employee surveys in aggregate to ensure anonymity, and share your plans for addressing respondents’ pain points.

Then, ask yourself: Do the benefits you offer today align with what your employees need? Are you offering a variety of benefits for different demographic groups? Where are the gaps between your current benefits and the things employees are asking for?

Knowing who you are as a company can help you curate the right benefit menu. What do you want for your employees? Whitlow calls this your “employee mission statement.”

One important demographic to engage: your older workers. These culture-carrying employees, who are approaching retirement, will be leaving with deep institutional knowledge. It’s crucial their knowledge is passed on. While you get a succession plan in place, keep older workers engaged by adding more skills to their palettes through reverse mentoring or formal educational reimbursement.

Remember that surveying employees should be an ongoing action. Revisit your surveys on a regular cadence to ensure they’re still aligned with your mission, vision, values, and needs. The right cadence will depend on your organization’s capabilities and goals, but many companies choose to survey employees at least once a year.

Educate and Inform

It’s not worth having superior financial wellness benefits if your employees don’t understand what you’re offering. To close the perception gap, “Show current and prospective employees the benefits awarded to them on an annual basis, including both direct and indirect compensation,” says Doss.

Communicate this information via multiple channels to resonate with different demographic groups. It’s up to employers to make benefits communications available through different media, easily accessible, and available in multiple languages. For instance, you might use infographics, pre-recorded videos, live, virtual meetings, and written articles to explain your benefit package in different ways. You might try incorporating this shift in open enrollment and benefits materials through anecdotes, employee testimonials, and lunch-and-learn sessions. Steer away from a list of features and lean into stories that explain the value.

Remember that communication channels should run both ways, so give teams plenty of options for asking questions and giving feedback.

When your benefits include a financial wellness program that addresses the unique challenges and goals of your whole employee population, individual employees are more likely to feel cared for, and to stick around.

“Your current employees are the culture carriers of your organization,” says Whitlow. “Those employees are the secret to attracting and attaining better candidates who are going do the same thing in the future. It’s a cycle. And it’s through this cycle that your company can find long-term sustainability, because your people, your most valuable asset, are going to attract new people to your business and keep your customers happy.”

This document, Fact Sheet 2024-19, includes 18 questions and answers on topics such as taxation and reporting, repayment, and how SECURE 2.0 specifically updates the disaster rules that have been in place since 2017. Key clarifications in the document include the following:

- Distributions and loans are available only to individual participants or IRA account owners who have experienced an economic loss due to a qualified disaster and whose principal residence is in the disaster area. Dependent and beneficiary residences do not count.

- Qualified disasters will be listed in the FEMA website on declared disasters.

- The economic loss does not need to be related solely to damage to the individual’s residence. Losses related to displacement and job loss would count as well.

- The $22,000 distribution limit is per person, per disaster. It is not per plan or per IRA, nor is it an annual limit.

- A plan sponsor can choose to permit disaster distributions, expanded disaster loans, or delayed loan repayments. Plan sponsors can also choose to permit some or all these options.

- Unlike some other SECURE 2.0 distribution provisions, qualified disaster distributions are a new type of permissible distribution event. Therefore, if the plan is amended to allow such distributions, a participant could take a qualified disaster distribution without having to qualify for another distributable event under the plan (e.g., a hardship).

- As with CARES Act COVID-related distributions, income taxes can be spread out over three years, and the 10 percent early distribution is waived.

- The distribution is not taxable at all if it is repaid to an eligible retirement plan within three years. The repayment to a retirement plan is classified as a rollover contribution. Therefore, plans that do not allow for rollover contributions cannot allow for distribution repayments unless their plans are amended.

- Generally, all retirement plan types are eligible except for private, tax-exempt 457(b) plans.

- As with CARES Act COVID-related loans, qualified disaster loans may be increased to 100 percent of a participant’s account balance up to $100,000.

- Existing loan repayments may be delayed for up to one year for participants in qualified disaster areas.

For more information on federal disaster distributions and loans under SECURE 2.0, please review our Federal Disaster Distributions and Loans infographic and reach out to your CAPTRUST advisor.

A successful investor maximizes gain and minimizes loss. Though there can be no guarantee that any investment strategy will be successful and all investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal, here are six basic principles that may help you invest more successfully.

Long-Term Compounding Can Help Your Nest Egg Grow

It’s the rolling snowball effect. Put simply, compounding pays you earnings on your reinvested earnings. The longer you leave your money at work for you, the more exciting the numbers get. For example, imagine an investment of $10,000 at an annual rate of return of 8 percent. In 20 years, assuming no withdrawals, your $10,000 investment would grow to $46,610. In 25 years, it would grow to $68,485, a 47 percent gain over the 20-year figure. After 30 years, your account would total $100,627. (Of course, this is a hypothetical example that does not reflect the performance of any specific investment.)

This simple example also assumes that no taxes are paid along the way, so all money stays invested. That would be the case in a tax-deferred individual retirement account or qualified retirement plan. The compounded earnings of deferred tax dollars are the main reason experts recommend fully funding all tax-advantaged retirement accounts and plans available to you.

While you should review your portfolio on a regular basis, the point is that money left alone in an investment offers the potential of a significant return over time. With time on your side, you don’t have to go for investment “home runs” in order to be successful.

Endure Short-Term Pain for Long-Term Gain

Riding out market volatility sounds simple, doesn’t it? But what if you’ve invested $10,000 in the stock market and the price of the stock drops like a stone one day? On paper, you’ve lost a bundle, offsetting the value of compounding you’re trying to achieve. It’s tough to stand pat.

There’s no denying it—the financial marketplace can be volatile. Still, it’s important to remember two things. First, the longer you stay with a diversified portfolio of investments, the more likely you are to reduce your risk and improve your opportunities for gain. Though past performance doesn’t guarantee future results, the long-term direction of the stock market has historically been up. Take your time horizon into account when establishing your investment game plan. For assets you’ll use soon, you may not have the time to wait out the market and should consider investments designed to protect your principal. Conversely, think long-term for goals that are many years away.

Second, during any given period of market or economic turmoil, some asset categories and some individual investments historically have been less volatile than others. Bond price swings, for example, have generally been less dramatic than stock prices. Though diversification alone cannot guarantee a profit or ensure against the possibility of loss, you can minimize your risk somewhat by diversifying your holdings among various classes of assets, as well as different types of assets within each class.

Spread Your Wealth Through Asset Allocation

Asset allocation is the process by which you spread your dollars over several categories of investments, usually referred to as asset classes. The three most common asset classes are stocks, bonds, and cash or cash alternatives such as money market funds. You’ll also see the term “asset classes” used to refer to subcategories, such as aggressive growth stocks, long-term growth stocks, international stocks, government bonds (U.S., state, and local), high-quality corporate bonds, low-quality corporate bonds, and tax-free municipal bonds. A basic asset allocation would likely include at least stocks, bonds (or mutual funds of stocks and bonds), and cash or cash alternatives.

There are two main reasons why asset allocation is important. First, the mix of asset classes you own is a large factor—some say the biggest factor by far—in determining your overall investment portfolio performance. In other words, the basic decision about how to divide your money between stocks, bonds, and cash can be more important than your subsequent choice of specific investments.

Second, by dividing your investment dollars among asset classes that do not respond to the same market forces in the same way at the same time, you can help minimize the effects of market volatility while maximizing your chances of return in the long term. Ideally, if your investments in one class are performing poorly, assets in another class may be doing better. Any gains in the latter can help offset the losses in the former and help minimize their overall impact on your portfolio.

Consider Your Time Horizon in Your Investment Choices

In choosing an asset allocation, you’ll need to consider how quickly you might need to convert an investment into cash without loss of principal (your initial investment). Generally speaking, the sooner you’ll need your money, the wiser it is to keep it in investments whose prices remain relatively stable. You want to avoid a situation, for example, where you need to use money quickly that is tied up in an investment whose price is currently down.

Therefore, your investment choices should take into account how soon you’re planning to use your money. If you’ll need the money within the next one to three years, you may want to consider keeping it in a money market fund or other cash alternative whose aim is to protect your initial investment. Your rate of return may be lower than that possible with more volatile investments such as stocks, but you’ll breathe easier knowing that the principal you invested is relatively safe and quickly available, without concern over market conditions on a given day. Conversely, if you have a long time horizon—for example, if you’re investing for a retirement that’s many years away—you may be able to invest a greater percentage of your assets in something that might have more dramatic price changes but that might also have greater potential for long-term growth.

Note: Before investing in a mutual fund, consider its investment objectives, risks, charges, and expenses, all of which are outlined in the prospectus, available from the fund. Consider the information carefully before investing. Remember that an investment in a money market fund is not insured or guaranteed by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporate or any other government agency. Although the fund seeks to preserve the value of your investment at $1 per share, it is possible to lose money by investing in the fund.

Dollar Cost Averaging: Investing Consistently and Often

Dollar cost averaging is a method of accumulating shares of an investment by purchasing a fixed dollar amount at regularly scheduled intervals over an extended time. When the price is high, your fixed-dollar investment buys less; when prices are low, the same dollar investment will buy more shares. A regular, fixed-dollar investment should result in a lower average price per share than you would get buying a fixed number of shares at each investment interval. A workplace savings plan, such as a 401(k) plan that deducts the same amount from each paycheck and invests it through the plan, is one of the most well-known examples of dollar cost averaging in action.

Remember that, just as with any investment strategy, dollar cost averaging can’t guarantee you a profit or protect you against a loss if the market is declining. To maximize the potential effects of dollar cost averaging, you should also assess your ability to keep investing even when the market is down.

An alternative to dollar cost averaging would be trying to “time the market,” in an effort to predict how the price of the shares will fluctuate in the months ahead so you can make your full investment at the absolute lowest point. However, market timing is generally unprofitable guesswork. The discipline of regular investing is a much more manageable strategy, and it has the added benefit of automating the process.

Buy and Hold, Don’t Buy and Forget

Unless you plan to rely on luck, your portfolio’s long-term success will depend on periodically reviewing it. Maybe economic conditions have changed the prospects for a particular investment or an entire asset class. Also, your circumstances change over time, and your asset allocation will need to reflect those changes. For example, as you get closer to retirement, you might decide to increase your allocation to less volatile investments, or those that can provide a steady stream of income.

Another reason for periodic portfolio review: your various investments will likely appreciate at different rates, which will alter your asset allocation without any action on your part. For example, if you initially decided on an 80 percent to 20 percent mix of stock investments to bond investments, you might find that after several years the total value of your portfolio has become divided 88 percent to 12 percent (conversely, if stocks haven’t done well, you might have a 70-30 ratio of stocks to bonds in this hypothetical example). You need to review your portfolio periodically to see if you need to return to your original allocation.

To rebalance your portfolio, you would buy more of the asset class that’s lower than desired, possibly using some of the proceeds of the asset class that is now larger than you intended. Or you could retain your existing allocation but shift future investments into an asset class that you want to build up over time. But if you don’t review your holdings periodically, you won’t know whether a change is needed. Many people choose a specific date each year to do an annual review.

Source: Broadridge Investor Communication Solutions, Inc.